Algonquin chiefs disappointed but unsurprised by radioactive dump approval

Some Algonquin leaders are looking at legal action after a highly contested radioactive waste site near the Ottawa River was approved.

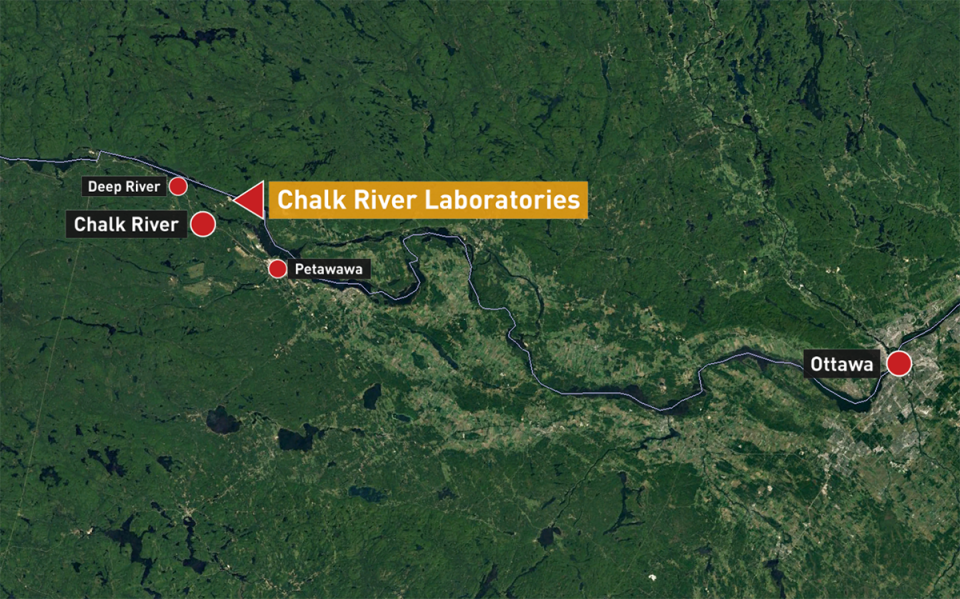

This week the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission approved Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) proposal to build an engineered mound or "near surface disposal facility" close to the company's nearly 80-year-old Chalk River site upstream from Ottawa and Montreal.

The site, like all of the broader Ottawa area, is unceded Algonquin territory and the facility would be about a kilometre from the river, an important Algonquin waterway for thousands of years.

The decision also determined that CNL had adequately consulted and accommodated Indigenous groups throughout the process.

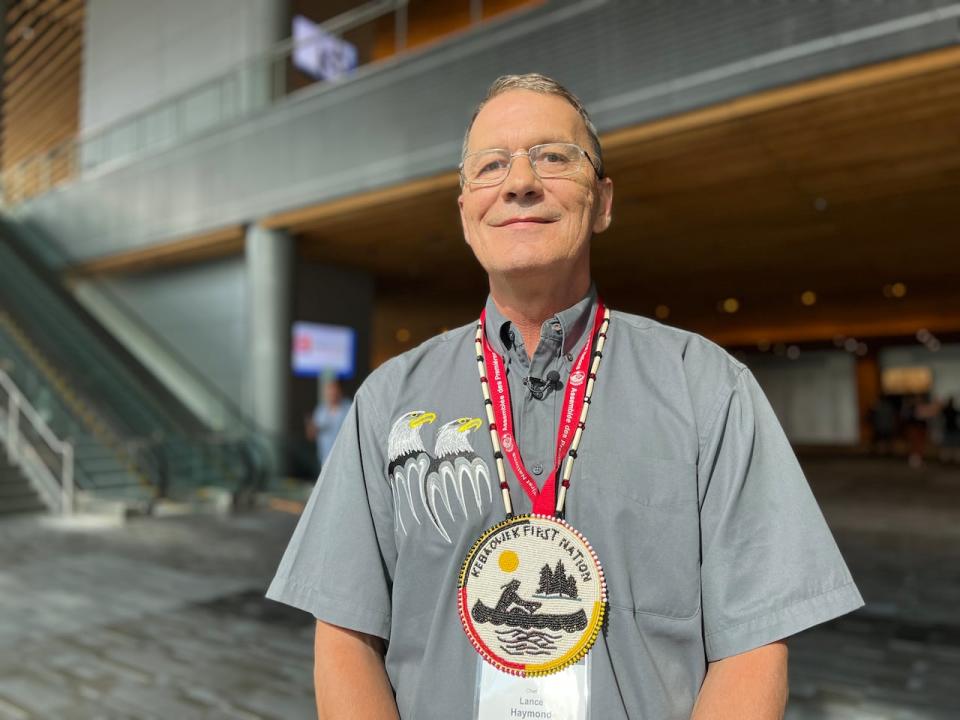

Chief Lance Haymond of Kebaowek First Nation disagrees.

"We got brought into the process way too late after many studies and decisions had already been taken," he said.

Lance Haymond, chief of Kebaowek First Nation northwest of the site, has fiercely opposed construction and feels Indigenous groups and communities were not involved early enough in the project. (Ka’nhehsí:io Deer/CBC)

CNL notified the commission of its intention to make this application in October 2015 and sent it in March 2017.

Between that, the commission put out a notice of its environmental assessment and started reaching out to Algonquin and other Anishinaabe communities, plus the Métis Nation of Ontario, in May 2016 by sending letters.

The commission held public hearings in 2022 and a final submission hearing this past August.

Ten of the 11 federally recognized Algonquin communities, including Haymond's, have fiercely objected to this proposal from the onset, citing concerns about water contamination, encroachment on sacred territory and wildlife.

Approval came as a blow, but not a shock.

"Very, very, very disappointed," Haymond said, "but really, quite honestly, not surprised."

"They always knew they wanted to do this and they were going to do it with or without us," said Chief Dylan Whiteduck of Kitigan Zibi Anishinābeg First Nation.

Potential negative environmental impacts

According to a project description, the site would include containment cells, a base liner and cover and a system to detect leaks of its "low-level radioactive waste."

CNL made the case that a permanent facility offers better protection of the waste it legally has to do something with compared to temporary storage and that because 90 per cent of the waste is at Chalk River, it should stay there.

The facility is on a sloped rock ledge where water flows away from the river and is above its maximum flood level, the commission said, and its wastewater network is designed to handle "back-to-back, 100-year, 24-hour storm events."

The commission wrote that the waste disposal site "is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects" (and is not technically a '"dump" because of the containment layers).

The chiefs are not convinced.

"We are very fearful that in 10, 15, 20 years, this project will continue to pose a risk and a danger to my members and in general to all Canadians who use and depend on the Ottawa River as their drinking water source," Haymond said.

A map of the area around the Ottawa River, indicating the Chalk River Laboratories site where the radioactive waste dump was given approval to be built. (CBC)

"We're just worried about the impacts of this, the longevity of this project," said Whiteduck. "It just feels too rushed."

Both Haymond and Whiteduck said they are exploring all of their legal options at this time, including a judicial review.

Concerns over lack of local supports

Gordon Edwards, president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility (CCNR), was consulted about the proposal.

Along with the site being close to the river, Edwards also takes issue with the lack of consent from Indigenous groups and municipalities that use the river.

We are the ones, our grandchildren and great grandchildren. They're the ones who are going to suffer the consequences if things are done poorly - Gordon Edwards, CCNR

"It seems that the decision to approve this dump has been made largely to service the needs of the industry and the wishes of the industry, not the wishes of the Canadian people." he said.

It's not the industry that could face long-term negative impacts, Edwards said, but the general population.

"We are the ones, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren. They're the ones who are going to suffer the consequences if things are done poorly."

CNL's ongoing commitments

CNL said it intends to meet all the commitments that it made to the Indigenous groups consulted, and "continue to offer them an opportunity to be involved in the project in the manner that they choose to do so."

The Algonquins of Pikwakanagan gave consent and entered a formal partnership with CNL, which said there will be regular Pikwakanagan monitoring at designated sites.

It's not clear yet when shovels will be in the ground, but the facility is expected to take about three years to construct.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News