‘I am not a Satanist!’: meet the great blasphemer of contemporary art

When Maurizio Cattelan was invited this year to participate in the Vatican’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, he was, he says, “the first to be surprised”. At 63, the Italian retains a reputation as the great blasphemer of contemporary art, whose mordant conceptual work has often had a pop at the Catholic Church.

One of his best-known sculptural tableaux of hyper-realistic effigies and stuffed animals consists of a wax statue of Pope John Paul II crushed by a meteorite. “Sacrilege!” cried Cattelan’s critics, who vandalised La Nona Ora (1999) when it was shown in Poland, the pope’s homeland, in 2001.

Yet, says Cattelan, speaking to me over Zoom from his Milanese apartment, before an elaborate Art Nouveau wardrobe that frames what he calls, with characteristic self-deprecation, “my horrible face” (with its distinctive aquiline nose), La Nona Ora is “absolutely not” anti-Catholic.

“At first glance,” he concedes, “it’s not convincing as a warrior defending the faith.” But, he tells me, “it’s an image of strength. The pope is still holding the cross, and not completely flattened. It’s not so different from Jesus Christ on the cross. Both are an image of torture.”

Cattelan grew up in a working-class Catholic family in Padua, and used to be an altar boy: “I’ve been raised,” he assures me earnestly, “in the shade of the bell tower of my Church.” Even the catalogue that accompanied his 2011 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York looked like a Bible. When I ask if he considers himself a satirist, he mishears me and shakes his head: “I’m not a Satanist!”

Is that sunlight around his head – or a halo? Perhaps this inveterate mischief-maker – who once portrayed a rich collector’s supermodel wife as a nude, wall-mounted hunting trophy – really has good intentions. If it were a painting, a screenshot from our interview of a smiling Cattelan, with wire-rimmed specs and a flyaway grey quiff, could be called The Penitent.

Repentance is certainly the context for his contribution to the group show within the Holy See Pavilion, opening this Saturday. For Cattelan, the Vatican’s decision to stage its pavilion within a functioning women’s prison on the Venetian island of Giudecca is a “compassionate” and “revolutionary” gesture, because “it turns the spotlight on people who live on the margins of society”. Inspired by such a “charged location”, he decided to show on the façade of the prison’s chapel a vast wall-painting reproducing a black-and-white photograph of the soles of a man’s feet, which he is calling Father.

“It could be my father, anybody else’s father, or the Father, the authoritarian figure of the Church,” he explains; either way, “it’s an image of powerlessness.” Yes, Cattelan admits, he had “issues with authority” while growing up, which continue to manifest themselves – he laughs – in “the work that I produce”; yet, Father isn’t, or isn’t only, about indulging an adolescent, oedipal impulse to topple an omnipotent paternal figure.

“Actually, I see it as a deposition,” he continues, referring to artistic representations of Christ’s descent from the cross. Those soles will be noticeably dirty – calling to mind the radical religious paintings of Caravaggio, who painted lowly models with grubby feet. “At some point, we will all have feet in such a position,” says Cattelan, who, in Now (2004), once presented a waxwork of John F Kennedy laid out in an open coffin, besuited but barefoot.

Cattelan isn’t expecting a backlash against Father, but acknowledges that controversy has often beset his work – mostly “created by newspapers, by media desperately needing headlines,” he suggests. “Chaos is not my priority. I like to underline things in society that disturb me, and probably disturb other people, and I try to do it in a way that can be listened [to].” His target audience is, he says, the “public”: “I don’t know if this is a pop attitude,” he tells me, “but I’m not interested in talking to the art world” – which, anyway, he suspects, doesn’t much like his recent work.

Even the decision to exhibit Him (2001), Cattelan’s notorious sculpture of a kneeling boy with the adult face of Adolf Hitler, at Blenheim Palace, the birthplace of Winston Churchill (where the artist had a solo show in 2019), wasn’t meant to be a provocation. Rather, he explains, Him represents the “clashing of evil and forgiveness”; at Blenheim, “you could have read it in a way where Hitler was there to ask forgiveness from England.”

Besides, he laughs, in Oxfordshire, “Oh, my god, the joke was on me!” Shortly after the exhibition opened, Cattelan’s satirical sculpture America (2016), a functioning solid-gold toilet, reportedly worth £4.8 million, was stolen. “Everyone thought that I was behind the theft,” he tells me. Was he? “Are you kidding?” Earlier this month, a 39-year-old man from Northamptonshire pleaded guilty to the crime.

Didn’t, though, Cattelan have a hand in the Guggenheim’s decision to offer America to Donald Trump’s White House instead of Vincent van Gogh’s Landscape with Snow (1888), which the president had requested? “I didn’t know anything at the time,” Cattelan tells me. “I wasn’t asked. It was a matter between the museum’s curators.”

How did he feel about their cheeky suggestion? “Definitely, it was a sort of provocation,” Cattelan says, “but it was a provocation not made on my behalf, and a little naïve. If I had to suggest something today [to lend to Trump, should he be re-elected], I would say either Picasso’s Dove or Guernica – because they’re symbolic of the times we are living in: one, asking for a more relaxed approach to life; the other, reminding us of a dangerous period ahead.”

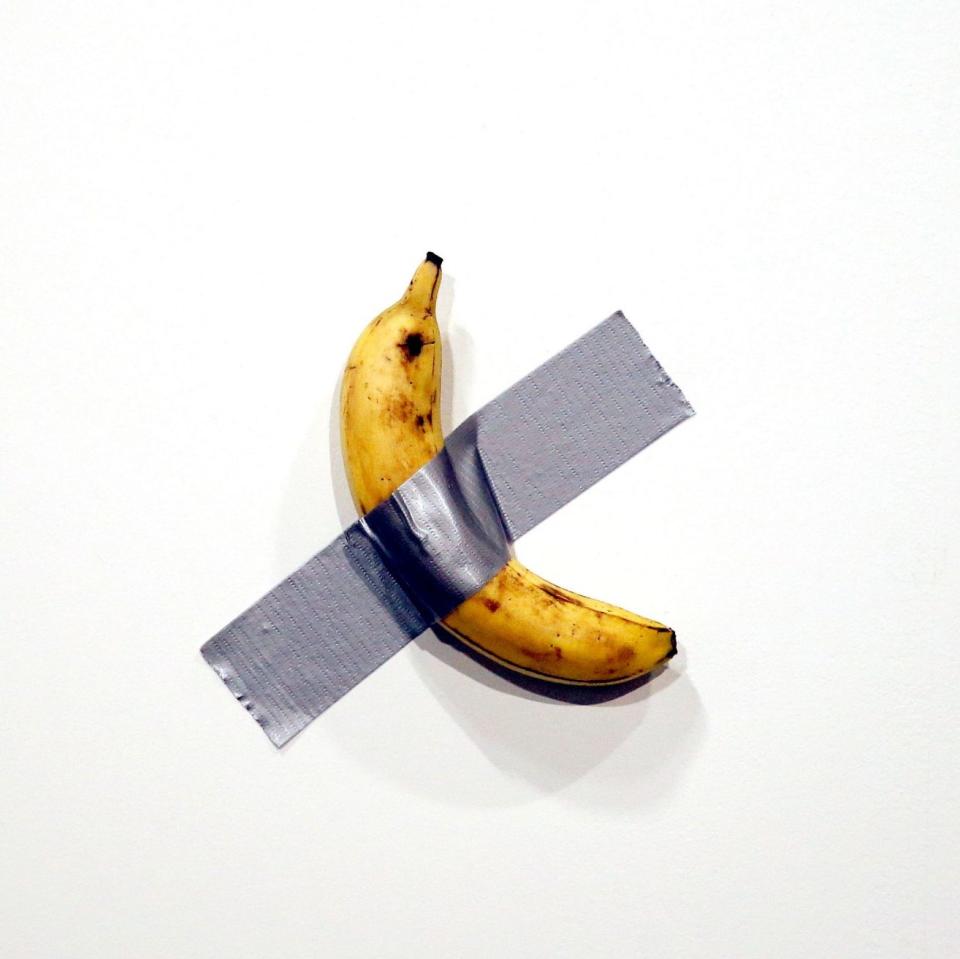

What, though, about Comedian (2019), a banana gaffer-taped to a wall that Cattelan offered for sale (in an edition of three, each priced at $120,000 (£91,000)) at an art fair in Miami: surely, that was intended to provoke? He shakes his head – although, he says, “it will always be funny”, because “a banana is such a comic fruit that comes with a punchline”, and “someone has spent a ridiculous amount of money.”

The truth is, says Cattelan, referring to the appetite today for contemporary art: “I don’t think anyone is looking for shocking works.” Rather, “the market is asking for something safe and easy to buy and sell” – a reflex, he believes, of a wider “moment of strong conformism” within society, brought about by the “disorienting … disruption” of the “digital revolution”. “We live in very interesting times,” he chuckles. “Everything is like: what the f---?”

In what way? “We are less free than during the 1970s,” he replies – although, he adds, “I have opportunities. I can do many things. I have never really been censored.” At the same time, he observes: “Experiments are disappearing. Painting is king right now.” And, he predicts, “there will be a moment where suddenly all this work will look dusty and useless.”

What about his own: does this artist who’s routinely called a “prankster” or “jester” think his deadpan jokes will last? In fact, he explains, the wit in his work is a feint: “I like to glaze my work with a taste of humour, but it’s a glaze. So, when you remove it, there is a different taste inside” – and it isn’t particularly palatable. “If you look very closely at all my works,” he tells me, “there is a sense of loss, death, and darkness.”

Suicide, for instance, is a recurrent motif. Several tableaux involve suspended animals or figures, including simulacra of himself hanging by the neck; in Bidibidobidiboo (1996), which he describes as “a fairy tale gone wrong”, a life-sized stuffed squirrel sits slumped over a table with a yellow Formica top, with a revolver at its feet.

“I am not a depressive person at all,” he assures me. “At school, they considered me a clown. But, sometimes, I don’t know…” He trails off. “Lately, there is a mask that I’m trying to remove. And this is a very hard job for me.”

What’s underneath? “We’ll find out. I want to be the first to know. It’s a process.” But, he tells me, we are all “the best deceivers of ourselves: we are the ones building our own prisons. The real enemy is within.”

This pursuit of self-knowledge explains why, for the first time in “five years”, he has agreed to do an interview face-to-face, albeit through a screen; usually, he prefers email, because, he says, “I like to control the output.” “Sometimes, you need to test yourself, to check what’s wrong with you, with myself,” he tells me. “So, whatever will come out from this, I will regret.”

Not too much, I hope? “I have already regretted it enough!” He laughs, before adopting the quiet, reflective tone of the confessional: “I am not such a bad person. I’m not someone who wakes up and my first priority is creating problems for other people. I’m an honest worker.” Your sins are forgiven, Maurizio. Go in peace.

The Holy See Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia opens on April 20. Information: labiennale.org

Yahoo News

Yahoo News