Anarchy in the UK: How the Sex Pistols’ snarling manifesto changed the face of punk

To an unsuspecting British public, the devil in pink announced himself on 4 September, 1976. With an opening cry of “Get off your a***!” this snarling creature writhed and sneered around the stage of Tony Wilson’s So It Goes show on Granada TV, his hair an untamed red, his shocking pink blazer shredded at the shoulder and held together with safety pins, and his true identity declared from the off: “I am an antichrist! I am an anarch-ist!” As a woman in a stencil-sprayed Nazi uniform danced beside him and his lairy bandmates made the sound of a biker gang roaring up outside your local church meeting with flaming torches aloft, he announced his devious intent, too. “I wanna be anarchy,” he barked like a hyena trapped in barbed wire, “get p*****, destroy!”

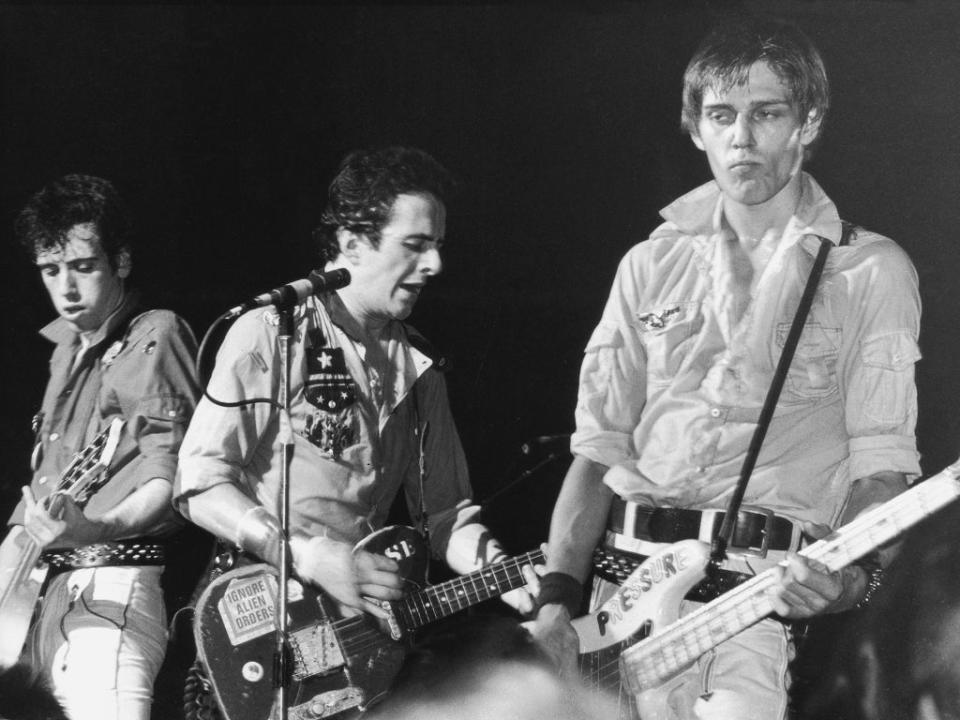

In the three-and-a-half minutes of the Sex Pistols’ first TV appearance – in which they played their debut single “Anarchy in the UK”, released 45 years ago this week – everything changed. What had thus far been a thriving, confrontational subculture gradually building a following among London’s art, rock and fashion crowds now broke the surface of popular culture, landing with the shock of a lightning bolt. The prog fans were disgusted by their uncultured primal racket; what corners of middle England had tuned in were outraged and terrified by their savage cries of sedition. But a generation of young music fans – previously without identity or musical hope in an age of slick disco and expensive orchestral rock – were excited, inspired and galvanised by punk’s ravenous rallying cry.

“Something needed to happen to stir things up back then,” says Glen Matlock, the Pistols bassist in 1976. “It was all quite turgid. If we’d done what everybody else was doing at the time we’d have been a lite jazz rock funk band, kinda like Kokomo… You know that bit in The Blues Brothers where John Belushi says, ‘We’re getting the band back together because we’re on a mission from God’? Now I don’t know that we was on a mission from God, but I do think we was on some kind of mission to educate the masses, provide an alternative voice. There was a dearth of music for young people that was of any consequence back then, and I think our mission was to try and stir it up a little bit.”

In their early days, the Sex Pistols were a dysfunctional sort of insurrectionist gang. Inspired by spending six months on the New York punk scene with The Ramones, the New York Dolls and Television, manager Malcolm McLaren had pulled them together from faces that hung around, worked in or – in guitarist Steve Jones’s case – shoplifted from his and Vivienne Westwood’s S&M-themed “anti-fashion” boutique SEX on the King’s Road. Matlock, Jones and drummer Paul Cook were playing together as The Strand before singer John Lydon, renamed Johnny Rotten for added gutter appeal, was spotted in an “I Hate Pink Floyd” T-shirt in the street. He auditioned by singing along to Alice Cooper on the SEX jukebox and was recruited as frontman for the renamed Sex Pistols after Television’s Richard Hell and New York Dolls’ Sylvain Sylvain had both turned down the role.

“When you do something like that, it’s just the four of you and the people who are helping you out against the world,” says Matlock – but a band of lifelong compadres they were not. “We’d row like cats and dogs and hate each other, but we worked well as a unit,” Lydon told a Classic Albums documentary in 2002. “A good little fighting firm.”

Revolving around SEX, however, they were immaculately placed. “We were at the epicentre of the hippest place in London at that time when nothing else was going on,” Matlock argues. “[Malcolm] was mates with a guy called Nick Kent, who went on to become the star writer and Lester Bangs of the NME, who actually gave us a tape from his mate with a song on it, which we loved, and we did it. We didn’t know what it was about, we didn’t realise it was about a car, but it was ‘Roadrunner’ by Jonathan Richman – his mate was John Cale who’d produced the album and it was a cassette of half the album about a year before it got released. Nobody is in that position to be that hip, and that’s what we were.”

Their shows at art colleges, Soho strip clubs and fashionable underground parties were proving inspirational, though, as musicians who saw them play felt compelled to emulate their unpractised three-chord rampages, starting new bands or changing direction in their image. Joe Strummer’s The 101ers became The Clash, while the 40-strong audience of a legendary gig at the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall in June 1976 included future members of Joy Division, The Fall, Buzzcocks and The Smiths.

“There were bands like The 101ers, The Stranglers, Eddie And The Hot Rods, and they’d been pub bands for a long time, top of the bill at certain pubs and the Marquee,” says Jordan Mooney, punk style queen of ’76 and that dancing Nazi on So It Goes. “Then they just missed the boat. It was just like a horse race – they couldn’t see what was coming behind them. The Pistols swept by them and knocked them for six.”

The sonic filth amassed; the fury soon followed. Lydon was a tempestuous and occasionally destructive presence onstage – he destroyed headliners Eddie and the Hot Rods’ equipment at one support show – and McLaren spurred them on to chaos. Mooney recalls a gig at artist Andrew Logan’s loft, when McLaren encouraged her to run onstage naked to cause some outrage for Nick Kent’s first NME review of the band.

“I said, ‘I’m not gonna do that, it’s really awful’,” she says. “’If John does something when I’m onstage then he has to prove that he’s man enough to do it to me, I’m not gonna just exhibit myself.’ So I went onstage and John ripped my top off and my bra and ended up strangle-holding me on the floor, which was very graphic and good. There’s a great shot of Steve Jones – his eyes are like great big beacons. They used it on flyers for following gigs.”

Such transgressive attitudes bled out to the Pistols’ audience. At a gig in the Nashville Room in April ’76, a fight broke out in the crowd when someone tried to steal Westwood’s seat. Sid Vicious, who was a fan of the band before becoming their bassist in 1977, “got a bit annoyed”, says Mooney. “In one seamless movement, he seemed to be able to get his belt off his trousers and have it ready to smack someone round the head with it.”

Matlock remembers a show in Dundee where the band were bottled off two songs in. “We hid behind the door behind the drumkit until we could hear no more glasses being flung, then went out to go and get a drink when we thought everyone was gone. There was some guys at the bar saying, ‘Why didn’t you come out and do any more numbers?’ We said, ‘Well, you were throwing glasses at us.’ And they said, ‘We’d read you like that.’”

One iconic set took place at Screen on the Green in August, where The Clash made their live debut. “They didn’t have a stage there,” says Matlock, “So the deal was [The Clash] could support us if they got a stage together. They had to actually build it! We got out and played and John had come from the dentist a couple of days earlier on and had a crown, and he knocked it out on the microphone, so in the front row is everybody looking for his tooth – Siouxsie in a bondage outfit and Billy Idol all scrambled on the floor looking for John’s crown.”

A week after the Pistols had caused mayhem in the So It Goes studios by running through three songs instead of their agreed one, the punk uprising cohered at the legendary 100 Club Punk Special. “There was something in the air that had really turned a corner,” says Mooney. “We were in the middle of a vortex, you’re inside it and it’s spinning around you – you don’t actually see until maybe years later what it looked like from outside, because you’re in the eye of the storm of it all. It started to make me realise that this was something big.”

Key to the phenomenon was what Matlock calls the Pistols’ “calling card” – “Anarchy in the UK”. Written at the band’s Denmark Street rehearsal room, it emerged from a typical bout of Pistols bravado. “Steve was supposed to come up with something and he hadn’t come up with anything,” recalls Matlock. “I sort of had a go at him. I said, ‘I feel like I do all the work’. He says, ‘If you’re so clever, what you got, then?’ I didn’t really have anything. I had a couple of ideas in the back of my head that I’d been mucking around with on my acoustic at home.” The opening chord sequence, he claims, was an attempt to emulate the theme music from Sunday Night at the London Palladium. “It’s an overture,” he says.

As the track came together, Lydon – who often kept his lyrics to himself - pulled out some pre-written words. “He said, ‘That’s great, I never thought you’d come up with an idea that fitted these words’,” says Matlock. “He never once said, ‘I’ve got these words – have you got an idea for them.’ The whole anarchy thing, I know he’d been talking with Malcolm and [artist] Jamie Reid, as we all had, knocking ideas around. Malcolm was always going on about ‘the band should write a manifesto, what we’re all about’, and that was our manifesto, really.”

Punk was suddenly as urgent and dangerous as the sexy young assassins had dreamt

John Robb, singer with The Membranes

What did Matlock make of the lyrics? “At the time I stood by them. I felt things needed to be shaken up. I think he was right about the fact that the future dream was a shopping scheme – that’s what most people seem to wish for, which is a bit sad. Anarchy in the UK… I don’t know how politically astute that is. It’s a little bit naïve, but we were 19 at the time. But [Lydon]’s come out as a Trump and Farage supporter, so…”

An early attempt to record the song with producer Dave Goodman came to nothing. “I wanted to make the heaviest song that had ever been in the universe,” Goodman told Classic Albums, while Jones complained of having to play the song “about a f***ing hundred times. My fingers were bleeding.” According to Matlock, it was McLaren’s interference that did it for the session.

“[Goodman] was fine,” he says, “but he had Malcolm McLaren sitting at his elbow telling him it wasn’t exciting enough when it was perfectly good. It was getting faster and faster and Dave, who was given a shot to produce it, couldn’t really tell Malcolm to piss off. We went on strike and Paul suggested [another producer] Chris Thomas. We met up with him and we said, ‘We don’t want Malcolm there.’ He said, ‘Fair enough.’ He was in a position to not have Malcolm there and we did it in five takes. The first half is from take three and the second half is from take five, spliced together. It finishes the way it did because the tape ran out. But it sounds good so we left it.”

On its release on 26 November, “Anarchy in the UK” hit the Top 40 and blew the lid off punk for the nation’s disenchanted musical youth. Wire’s Colin Newman would call it “the clarion call of a generation”. “Even if you look at it today, it was so groundbreaking,” says Mooney. “It’s so anarchic – you don’t sing about things like that. Nobody had sung anything like that… The youth of those days felt abandoned and they could see something that they could join. Not like a gang with a uniform but something they could change things by their looks, by their actions and by the music.”

“It was a sea-change moment,” says Matlock, and its ferocious attack can certainly be considered the root of most UK alternative guitar music ever since. Its cultural significance, however, was soon overshadowed by a storm of controversy. On 1 December, egged on by presenter Bill Grundy, the band made a legendarily foul-mouthed appearance on Thames Television’s early evening show Today – an event now somewhat celebrated but, according to Mooney, “the worst thing that could have happened to the Sex Pistols”.

“We never set out to do that,” says Matlock. “It’s just Steve Jones drank a bottle of Blue Nun by himself in the green room and started swearing his head off when it kicked in halfway through the interview. Behind the cameras, Malcolm McLaren had his head in his hands and when we left the set from the interview he says, ‘You’ve gone and done it now.’ He was bricking it! The next day he came into his own. Instead of him calling up trying to get us in the papers, the papers were calling him.”

Overnight, the Sex Pistols were public enemy number one. The Daily Mirror splashed the headline “The Filth and the Fury” and many dates on the planned UK tour were either cancelled or subject to strict obscenity restrictions. “That was the beginning of the end for me and the band, and Steve as well,” says Matlock, who’d leave the Pistols over his differences with Lydon – and frustrations at the single’s opening half-rhyme – within months. “It was almost too much too soon. It was fun, but it was also boring because we were cooped up all the time and we had to keep going to places to be seen to be turning up and playing in front of the local mayor and his dignitaries at the soundcheck, him approving it and, y’know, censorship, if he wasn’t gonna do that. I also thought it was stupid because we could go and do a tame version in the afternoon and then as soon as his back’s turned do what we wanted to do.”

“There were at least two occasions I can remember they called me up on the phone from where they were staying and said they didn’t want to go outside,” Mooney adds. “People were just looking at them wanting to pick a fight all the time – serious fights. Just because you sing about anarchy doesn’t mean to say that you’re a boxer.”

Yet the furore around “Anarchy…” and its ill-fated tour only helped stoke the punk fires. “The Anarchy tour was one of those thrilling moments when pop culture got too hot to handle,” says John Robb, singer with The Membranes and editor of Louder Than War magazine. “The moral panic of dusty old councils around the UK was the perfect response to bring a whole new raft of teenage punks to the cause. Punk was suddenly as urgent and dangerous as the sexy young assassins had dreamt. The crumbling old culture of the UK was a perfect backdrop to the vibrant electricity of the Sex Pistols – a band you could hardly see or hear, and that tantalising illicit thrill only added to their mystique and power.”

Anarchy might not have broken out in the UK, but punk had, out to scratch its savage sonic slogans across the chest of a bloated rock scene. That devil in the pink jacket certainly had one of the best tunes…

Read More

Sid Vicious is still punk’s biggest mystery, 40 years after his death

No future: 40 years since Sex Pistols stuck two fingers up at the British establishment

‘It’s the beginning of a new era’: the POC punk bands reclaiming pop-punk

The urgent need to make live music spaces safer for women

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die

Peter Jackson on The Beatles and Get Back: ‘I get the feeling history has arrived’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News