‘Anger is growing’: protests and strikes spread across France over pensions reform

Renaud, 49, leaned out of the window of his Paris bin lorry, which was being held in its depot by a barricade of strikers. “Emmanuel Macron doesn’t seem to be listening to the anger out there,” he said. “People don’t think we’re in a democracy any more.”

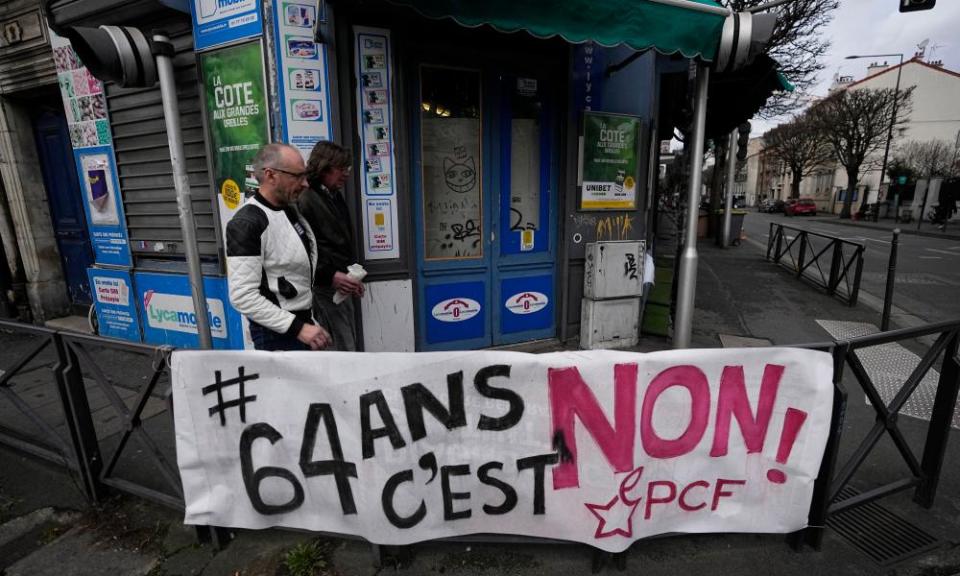

A refuse-truck driver for 22 years, Renaud had watched as his garbage processing plant was blocked for the 15th day of a rubbish-collection strike that has all but submerged half of Paris under 10,000 tonnes of waste. He couldn’t afford to strike and risk losing his daily income but understood the rage over Macron’s decision to use executive powers to push through an unpopular rise in the French pension age to 64 without a vote in parliament.

Everyone was talking about how the political system was collapsing, he said. “People are struggling, prices are going up. I already have to work extra jobs to make ends meet – carpentry, building, anything I can find.”

Protests intensified in France on Tuesday after the government narrowly survived a no-confidence vote. Over several nights of sporadic demonstrations there have been more than 1,500 protests in cities including Marseille, Lyon, Lille and Paris – where bins were set alight – as well as ring-road blockades, docker protests, barricaded university buildings, train-track invasions at stations, refinery protests and electricity blackouts by strikers. At Renaud’s depot, a crowd of students gathered to support the strikers.

“Everyone’s joining in, the government is afraid of more and more young people taking part,” said Céline, 53, a trade unionist for the leftwing CGT union who works in local government administration in Ivry, a Communist-run town on the south-eastern edge of Paris and has been on the barricades at the trash plant since 5am most mornings.

“There has been a denial of democracy,” she said. “Macron thinks of himself as a kind of king, Jupiter up high looking down on us. We’ve got to hold out until he listens.”

Related: Why are pensions such a political flashpoint in France?

At the depot, a slow dribble of very few rubbish trucks was now passing each day but not enough to ease Paris’s rubbish crisis. Meanwhile, the southern port city of Marseille called its own garbage strike, alongside other towns such as Le Havre.

The French president is facing his biggest ever domestic political crisis, less than a year after his re-election to a second term. A protest movement and on-off strikes against his unpopular pensions changes – at one point getting 1.28 million people out to protest in the street have persisted for two months but, last week, unable to garner enough support in parliament, the government used controversial executive powers to push the reforms through. On Monday, the government survived a no-confidence vote, but only by nine votes – sparking more demonstrators to take to the streets amid hundreds of arrests and clashes with police.

Some fear a new round of protests could echo the gilets-jaunes anti-government movement of four years ago. It is uncertain what Macron will propose to calm the storm on the streets. He will appear in a TV interview on Wednesday, but Elysée insiders have already ruled out a cabinet reshuffle or a referendum. Nor will Macron dissolve parliament and call a snap general election: Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally, currently the biggest single opposition party, could stand to benefit the most.

Meanwhile, Macron will press on, including by this weekend welcoming the UK’s King Charles for his first state visit and a banquet at the Palace of Versailles while protesters condemn him as haughty and monarchical.

“Anger is growing,” said Akli, 48, an Ivry council worker on the refuse barricades. “This has gone far beyond pensions, it is about our political system. The president has executive powers that need to be rethought. It’s about protecting France’s whole postwar system of social protection. It’s about hanging on to our welfare state, as Macron tries to unpick it – from housing benefits to the unemployment system. French people are well informed and politicised, they won’t let this pass.”

Outside the refuse centre, Ariane, a law student had arrived from the Paris university’s Tolbiac campus, which had been blockaded and barricaded before being evacuated by police. A member of an anti-capitalist revolutionary group, she was handing out flags to other students. “At the student meeting to vote on the university barricade, so many young people were talking about their experiences of police violence,” she said. “Young people are angry, more are joining in since the pension changes were pushed through. The government is afraid of a new youth movement taking part.”

Lawyers and magistrates’ unions have criticised the government over the policing of street protests and accused officers of making arbitrary arrests – including of medics, students and trade unionists, later released without charge. The police watchdog is investigating allegations that four young women in Nantes were sexually assaulted during police controls at a demonstration last week.

Outside the Duperré art school in Paris, students piled up a barricade of bins. Signs said raising the pension age to 64 would be met with a new May 1968, a reference to France’s famous students and workers’ strikes.

“Don’t underestimate people’s power to mobilise,” said Amina, 19, a textiles student from the Paris banlieue. “I’m afraid of police violence and terrified to demonstrate at night, but I’ll join in during the day.”

She was on the left, but had voted in for Macron in the final round of last spring’s presidential election in order to keep out Le Pen. “That doesn’t mean I agree with Macron’s ideas,” she said. “The working-class will bear the brunt of these pension changes, we see that in our families – there’s inequality and it’s unfair.” She lived with her single mother who was a maintenance worker at a hospital.

Another 19-year-old student, Bahia, who came from the countryside outside Lyon, had seen her mother suffer unemployment and burn-out. “This is about the whole democratic system – how many more laws could be passed using executive powers and without a parliament vote? It feels to us like the system is broken.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News