Who's for a Ruby Murray? The real people behind popular English sayings

Most people familiar with British cuisine will not be surprised to learn that the UK has just celebrated National Curry Week. In anticipation of the culinary festivities, Evening Standard journalist Ailis Brennan wrote on October 17 that “very few of us Brits can resist a Ruby Murray on a Friday night”. Obviously, she is not talking about a specific individual here. A Ruby Murray – or a Ruby, for short – is a well-known Cockney phrase for a curry. But why do we use this personal name to refer to the dish? And where do such phrases with names generally come from?

Ruby Murray is not the only phrase in English that contains a name. We can call a know-it-all a “smart Alec”, for example. A sudden event takes place before you can say “Jack Robinson” and someone who enjoys spying on others is a “peeping Tom”.

It is very tempting to assume that the name in such a phrase originally referred to a real person. This individual’s story would then somehow explain the current usage of the phrase. We all like things to make sense, after all. Unfortunately, our desire for meaning cannot always readily be satisfied, so we often just come up with a story that makes it seem sensible.

Biased Bob

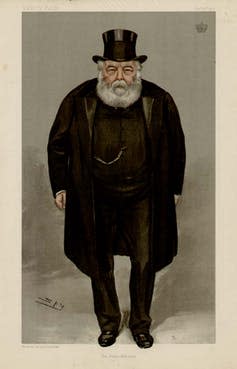

Take the phrase “Bob’s your uncle”. It appears to date back to the early 20th century and serves to signal the ease with which something can be accomplished. You might say, for instance: “To make a sandwich, put some cheese between two slices of bread and Bob’s your uncle!” But where does it come from? It is said that the Bob in the phrase is 19th-century prime minister Robert Cecil (1830-1903).

In 1887, he appointed his fairly inexperienced nephew Arthur Balfour (1848-1930) to the important post of chief secretary for Ireland. The decision took everyone by surprise and was criticised heavily: evidently, it was enough to have Bob (Cecil) as your uncle to achieve your goals, without any effort on your part.

All of this makes for a very captivating story. There is, however, no evidence from the period that “Bob’s your uncle” actually started out as some type of political slogan. Alternative theories are equally problematic. Some etymologists point to an obscure 1924 musical show bearing the phrase as its title.

It seems more likely, though, that the writer picked up an existing expression than coined a completely new one. Others see a connection with the 17th-century slang phrase “all is bob”, which was another way to say that all was good. Yet, whatever supposedly transpired in the intervening centuries remains unclear.

Lively Larry

Larry is known as a cheerful chap, but he suffers from the same kind of confusion as Bob. The name in the phrase “happy as Larry” is sometimes linked to the now obsolete noun “larry”. In some British dialects, it once served to convey the idea of confused excitement.

We can turn to Thomas Hardy’s (1840-1928) novel The Hand of Ethelberta from 1876 for an example: “My brain is all in a spin, wi’ being rafted up in such a larry!” The name might also be a reduced form of the old dialect word “larrikin”. At one time, people in Worcestershire and Warwickshire used it to refer to a lively but naughty young person. It still occurs in Australian English as a synonym for hooligan. We cannot really prove either etymology, however.

The following explanation speaks to our imagination much more anyway. The Larry in “happy as Larry” is Laurence Foley (1849-1917), an undefeated professional boxer and the so-called “Father of Australian Boxing”. The phrase alludes to the emotion that he felt when he retired at the age of 32. His last fight won him such a large amount of money that he must have been overjoyed. The question now is whether Larry’s story is any more believable than Bob’s. The evidence is ambiguous.

The earliest attestations of the phrase do seem to come from Antipodean texts coinciding with the end of Foley’s boxing career. Still, some of those cases predate his final match. Maybe, his contemporaries saw his happy retirement simply as a chance to give meaning to an existing expression that made little sense to them?

Glitzy Gordon

For both Bob and Larry, it has proven impossible to be sure that they refer to real people. Part of the reason is undoubtedly the generic nature of the two names. In fact, phrases very often feature personal names that were just very common in the period when they arose.

Jack in a “Jack of all trades” is an example and so are Tom in “tomboy” and Jones in “keeping up with the Joneses”. But such generic origins seem less likely for combinations of a first name with a surname – such as, for instance, Gordon Bennett. This phrase expresses amazement, disbelief or irritation. A distracted parent might exclaim: “Gordon Bennett, I forgot to pick up the children!”

The individual most frequently suspected of being its source is the American James Gordon Bennett Jr. He owned the New York Herald newspaper but was also famous, if not infamous, in the UK and France for his playboy antics and passion for daring boat, road and air races. The public’s typical reaction to his behaviour may well have inspired the phrase.

A second theory is that it is a euphemistic corruption of the expletive “gorblimey”, which is itself a softened and similarly sounding alternative to “God blind me” (another example of this phenomenon is the use of “Great Scott!” instead of “Great God!”). The two explanations are not necessarily mutually exclusive, by the way. People who wanted to avoid “gorblimey” may have resorted to the name Gordon Bennett because it was in the news a lot and sounded similar.

Ravenous Ruby?

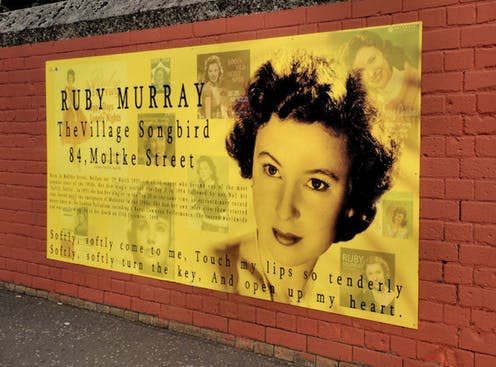

Phonetic resemblance brings us back to Ruby, at last. It is of course the rhyme of her surname Murray with curry that encouraged Cockneys to replace the one with the other in their slang. Why this name, though, and not, say, Johnny Surrey? Ruby Murray (1935-1996) was one of the most popular singers in the UK in the 1950s. One week in 1955, for instance, she had no fewer than five singles in the Top 20 at once.

The decade after the war was also the time that curry became a staple of British cuisine. Asian immigrants bought up bombed out cafes and chippies, added curry to the menu and got the post-pub crowd hooked by staying open late. You can easily imagine then how someone eating their exciting new take-out and listening to the radio saw the opportunity for the rhyme. Ruby Murray’s omnipresence in the 1950s is, in other words, the only reason why her name got attached to the food. But would it not make for a better story if she had a reputation of devouring a curry after every performance and people began calling the dish after her because of that?

You may have noticed that Ruby Murray is the only phrase in this article with a woman’s name. That is no accident: research has shown that most first names in use in English phrases refer to men. The exceptions include the use of “sweet Fanny Adams” to say “nothing at all” and that of “Aunt Sally” to point to an object of ridicule. The male predominance reflects our patriarchal history. But society is changing – and, hopefully, it won’t be long before every Tom, Dick and Harry uses the phrase “every Tom, Dick and Mary”.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Daniel Van Olmen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News