Asia’s arms race: potential flashpoints from Taiwan to the South China Sea

Global militarisation has increased rapidly over the course of the 21st century, with a clear recalibration towards the Asia Pacific. Between 2000 and 2021, annual military spending increased from $1.12trn (in 2020 dollar terms) to $2.11trn. In that time, the share of global defence spending in Asia and Oceania increased from 18% to 28%, according to data compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Growing concerns over China, whose defence spending has increased steadily for nearly three decades, has fuelled an arms race across the region, upending decades-long regional conventions and revealing several potential flashpoints.

Taiwan

The biggest concern about China’s military expansion is how it ties in to plans to annex Taiwan. The risk of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is the highest it’s been in decades, but predictions of when it might happen vary.

Recently a number of senior US military leaders have offered alarmingly imminent dates including 2023, 2025 and 2027. American assessments are crucial, given it’s possible the US military will help defend Taiwan against Chinese attacks, but some analysts caution that these military figures are likely exaggerating to lobby for more funding. Sources say the public predictions have frustrated Taiwan’s president, who is trying to ensure people are worried enough about the China threat that they support her policies, but not so much that they give up hope.

However, the scale of China’s military expansion offers analysts some clues to its ambitions for Taiwan.

While still spending a smaller share of its GDP on defence than the US, China’s defence budget will increase by 7.2% in 2023, taking it to the highest point it’s ever been. The US Department of Defense estimates that China’s real military spending could be up to twice as much as the officially reported figures. In response, the defence portion of the most recent US budget has prioritised ramping up the military presence in the Indo-Pacific. This month the US also approved the potential sale of $619m in new weapons to Taiwan.

Just as important as the increased spending is how it affects the balance of military strength in the region. In 2000, China was the second-largest defence spender in the Indo-Pacific. By 2021 it was spending more on defence than the next 13 countries in the region combined.

China has also taken great exception to a tripartite agreement between Australia, the US and the UK. The AU$368bn deal, known as Aukus, will see the US and UK help Australia acquire at least three nuclear-powered submarines over the next three decades. Aukus is widely seen as being aimed at countering China’s military expansion, and has drawn mixed reactions. China accused the allies of deception, using loopholes in non-proliferation treaties, and “walking further and further down the path of error and danger”. Australia’s defence minister responded by saying, “China invests … in its own defence capabilities; we are doing that in respect of ours.”

Helen Davidson in Taipei and Amy Hawkins

North Korea

Having launched about 90 ballistic missiles and other weapons in 2022 – more than in any other year – North Korea appears intent on setting a new record this year. It has held 11 rounds of missile tests, some involving more than one weapon, so far in 2023, including two intercontinental ballistic missiles and, according to state media, strategic cruise missiles with a nuclear capability.

In a sign that the regime in Pyongyang has no intention of relinquishing its weapons of mass destruction, it recently unveiled new, smaller nuclear warheads and vowed to produce more weapons-grade nuclear material. Kim Jong-un called for an “exponential increase” in the regime’s nuclear arsenal at the end of last year.

The North’s provocations are directed towards its nemeses: the US and South Korea. As March drew to a close, forces from both countries engaged in joint maritime exercises that included nuclear-powered aircraft carrier the USS Nimitz, days after they ended their largest joint military exercises in five years. The allies insist the drills are purely defensive in nature, but Pyongyang condemns them as a rehearsal for an invasion.

Rising tensions on the Korean peninsula have triggered a hardline response from South Korea’s conservative president, Yoon Suk Yeol, who has warned that Seoul will not provide a “single penny” to the North as long as it continues to develop nuclear weapons. More worryingly for those eager to dial down tensions, a serious debate is unfolding over whether Seoul should acquire its own nuclear deterrent – a move a majority of South Koreans support, according to polls.

In Japan, concern over North Korea and an increasingly assertive China has boosted the case for steering the country further away from its postwar “pacifism.” Late last year, the government of prime minister Fumio Kishida announced Japan would double defence spending to 2% of GDP by 2027, abandoning its self-imposed cap of 1% of GDP.

The increasingly unstable security environment in the Asia-Pacific has been the catalyst for a long-awaited thaw in relations between Japan and South Korea – both US allies with tens of thousands of American troops based on their territory.

In March, Yoon and Kishida became the first South Korean and Japanese leaders to hold bilateral talks for 12 years. Their summit in Tokyo came amid attempts to resolve disputes connected to their bitter wartime legacy, and resulted in an agreement to resume reciprocal visits and a security dialogue after a five-year hiatus.

Justin McCurry in Tokyo

South China Sea

The South China Sea is one of the most strategically and economically important waterways in the world. It is one of the world’s busiest trading routes, rich in marine life and is thought to contain significant reserves of oil and natural gas. It’s also highly contested.

China claims almost all of the South China Sea, with its so-called “nine-dash” line marking the limit of the country’s claim – though an international tribunal in The Hague has rejected this. The Philippines, as well as Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan also have overlapping claims. The US, while not a claimant, considers the water crucial to its national interests.

Under president Ferdinand Marcos, the Philippines has taken a much tougher stance on the dispute, with Manila accusing Chinese vessels of “aggressive actions” in the South China Sea.

Marcos has vowed the country “will not lose one inch” of its territory, and has overseen a massive shift in foreign policy, strengthening defence ties with the US and its allies.

In March the Philippines expanded US access to its military bases, enhancing Washington’s footprint in the region, and enabling it to more easily monitor Chinese activity in the South China Sea near Taiwan. It has also strengthened military ties with Japan and Australia, two US allies.

In contrast to neighbouring Southeast Asia countries that have expressed concerns over Aukus, which some nations fear could prompt an arms race that destabilises the region, the Philippines has supported the development.

The approach taken by Marcos, who came to power last year, is a stark contrast to that of his predecessor, former president Rodrigo Duterte. Duterte had sought closer economic ties with Beijing and was reluctant to confront China over its activities in the South China sea – even as China constructed military bases on human-made islands, and Chinese vessels harassed, or rammed, Filippine boats.

Rebecca Ratcliffe in Bangkok

Pacific Islands

Pacific leaders have repeatedly stressed that they don’t want to be drawn into a geostrategic contest between the US and China, and have resisted the notion of picking a side. They have also repeatedly said the climate crisis is their top security threat.

However, China is increasingly active in seeking influence among Pacific island countries, including in security and policing. These efforts have prompted something of a reckoning in Australia, New Zealand and the US, which have all moved to step up their diplomatic efforts.

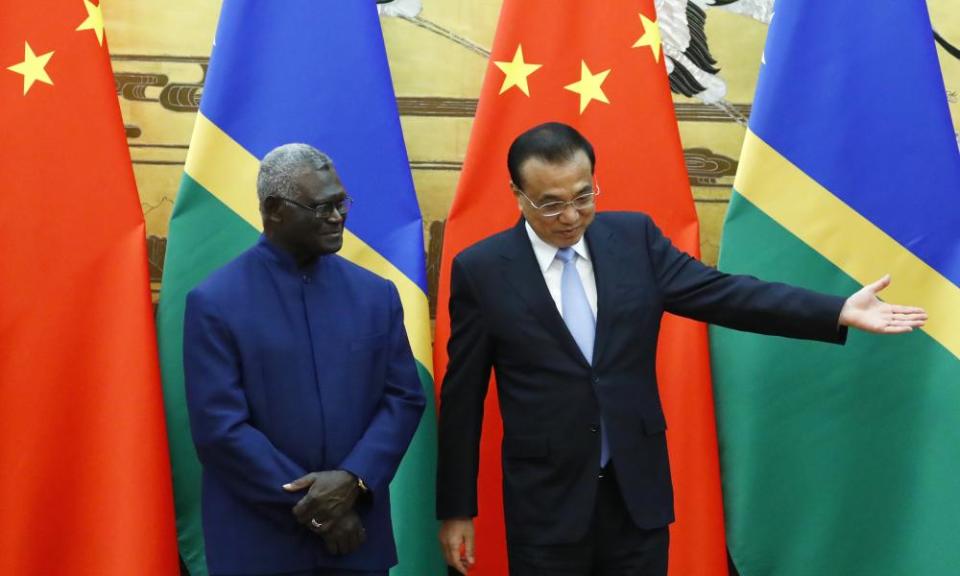

Beijing’s progress in the region was most sharply illustrated by the signing of a security agreement with Solomon Islands nearly a year ago.

A leaked draft suggested that the agreement would allow China to respond to requests from police and armed forces to carry out a range of tasks such as maintaining social order and protecting “the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in Solomon Islands”.

Australian officials had privately raised fears that the deal might pave the way for a future Chinese naval presence about 1,700km from the country’s coast, although the prime minister of Solomon Islands, Manasseh Sogavare, has repeatedly assured Australia and other countries that there will never be a foreign military base in his country.

China also sought a sweeping regional security deal with 10 Pacific countries last year, but this was rebuffed by Pacific leaders over concerns that Beijing was trying to bypass established structures such as the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF).

Other countries have scrambled to respond to China’s diplomatic pursuits. Since coming to power last year, Australia’s Labor government has placed a priority on restoring trust with Pacific leaders. The foreign affairs minister, Penny Wong, and others have made a series of high-level visits stressing that security should be the responsibility of the immediate region (not China). Australia aims to finish negotiating a bilateral security agreement with Papua New Guinea by the end of April, having signed a deal with Vanuatu in December.

The US has acknowledged its own need to step up in the region, which has seen it reopen its embassy in Solomon Islands in February, but western officials are under no illusions about the trends. Despite initial relief at the decision by Pacific island countries to defer China’s sweeping security proposals, the Australian government believes this may be only a temporary reprieve. A senior government figure conceded last year: “Things aren’t going back to the way they were.”

Daniel Hurst in Canberra

Yahoo News

Yahoo News