What the James Webb Space Telescope's discoveries on another planet mean — and don't mean — for the search for alien life

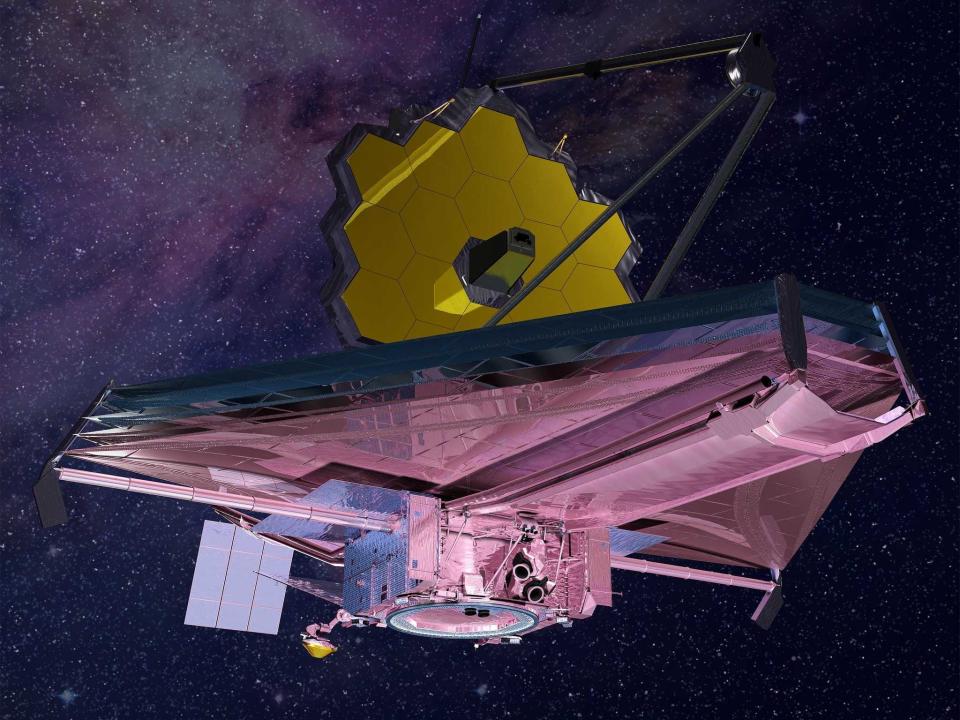

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope discovered signs of a vast ocean on the planet K2-18 b.

The exoplanet lies 120 light-years away, likely has an ice core, and may be a new type of habitable world.

Webb may have detected a molecule there that's only linked to life, but much more research is needed.

The James Webb Space Telescope has discovered evidence that a planet beyond our solar system may be covered in an ocean of water.

Astronomers can't directly look at the surface of the planet, called K2-18 b, but Webb analyzed its atmosphere for hints of what may lie below.

The results make this planet, just 120 light-years away, look more and more like a place that could be habitable for life.

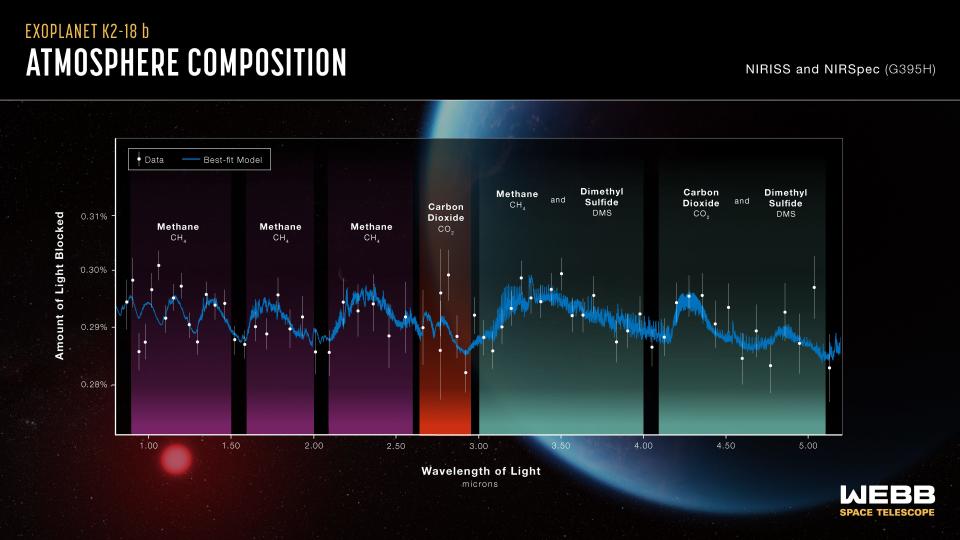

The most potentially game-changing discovery from the NASA observatory — and the one to be most cautious about — is a hint of a molecule called dimethyl sulfide (DMS), which is only known to come from life.

"We might be seeing literally the first steps towards identification of life elsewhere," Nikku Madhusudhan, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge who led the new research, told Insider.

Though intriguing, that data is uncertain and is not a clear detection of that molecule. It's too soon to cry "aliens," but astronomers are keen to investigate further.

Dimethyl sulfide would be a 'smoking gun' for life

The only thing known to make DMS is life, mostly phytoplankton in Earth's oceans. Therefore, if it were confirmed on K2-18 b, it would be a "very good smoking gun for some sort of biological activity," down there, Madhusudhan said.

However, such an extraordinary discovery requires extraordinarily strong evidence.

When Madhusudhan's team massaged the new Webb data to mimic a particular type of instrument error, the signal for DMS disappeared.

That's a strong mark against the molecule's existence on K2-18 b. It's one reason astronomers are extremely cautious about this possible detection and need another look at the planet.

Here's one way to put the potential DMS finding into perspective: Some scientists have developed the "confidence of life detection" (CoLD) scale, to rank the strength of evidence for alien life on a scale of one (weak) to seven (strong).

This is level one at most, Madhusudhan said. It may not even make the scale at all unless another set of observations finds the same signal.

"A lot more work is required before envisaging the possibility of alien life, beginning by a beyond-all-reasonable-doubt confirmation of the presence of DMS," said Doriann Blain, of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, who has previously studied K2-18 b.

Madhusudhan agrees. He hopes to publish new results from fresh Webb observations by this time next year, providing more evidence either for or against the presence of DMS on K2-18 b.

"Our discovery is the kind that, if it survives, you will look at it 10 years from now and say, well, that's where it all started," Madhusudhan said.

Webb solves the 'missing methane' mystery

What is clear in the data, and groundbreaking in its own right, is that Webb detected methane in the atmosphere of K2-18 b.

The discovery solves a decade-long "missing methane" problem, in which astronomers knew there should be methane in certain planets' atmospheres but they just couldn't find it.

Finding methane is important because it contains carbon, which is a foundational element for life as we know it.

"Even the most basic thing that we are saying — that we found carbon-based molecules — is a huge revolution in the field," Madhusudhan said.

Confirming these findings requires a lot more observation of K2-18 b. Over the course of the next year, Madhusudhan has time scheduled with Webb to observe the planet more, as does another team of astronomers.

Webb spotted molecules in the planet's atmosphere that Hubble couldn't see

At 2.6 times the size of Earth, and 8.6 times its mass, K2-18 b is not the type of planet that scientists traditionally consider when they're looking for alien life.

It's a "sub-Neptune" or a "mini-Neptune." Its interior is probably filled with ice, rather than rock. As Blain put it: "K2-18 b is not exactly an Earth twin."

But previous observations of this planet, with the Hubble Space Telescope, hinted that it could have water vapor in its atmosphere. That was intriguing enough that Madhusudhan and his collaborators peered at it with Webb earlier this year.

When starlight passes through K2-18 b's atmosphere, the molecules in the air there will absorb some wavelengths of light and reflect others. By analyzing which wavelengths make it through and shine at Earth, across the infrared spectrum of light, Webb can identify the unique "spectral" fingerprints of different compounds in the atmosphere.

Webb can analyze those spectra in much higher resolution than Hubble. The results, shared on Monday by NASA and the European Space Agency, were clear: There's probably carbon dioxide and methane in that atmosphere.

These findings, which are set to be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, put a new type of planet on the map in the search for alien life.

Mini-Neptunes haven't been considered the best alien-life candidates in the past, but they seem to be the most common type of planet in our galaxy. Now, with Webb's power, astronomers can see exactly what's in their atmospheres.

"It opens up other possibilities," Eliza Kempton, an astronomer at the University of Maryland, who specializes in the spectra of exoplanet atmospheres, told Insider.

"This is the first sub-Neptune-sized planet to show us a beautifully featured spectrum. This is something that we've been waiting for, for a long time," she said.

This could be a new type of world: the 'Hycean' planet

Planet K2-18 b could be the first known "Hycean" world — a theoretical type of planet with a thick hydrogen atmosphere and a surface covered in an ocean of water.

The Webb observations of K2-18 b are "remarkably well in agreement" with models predicting the atmospheres of Hycean worlds, according to Markus Scheucher, who led some of those models.

Namely, the presence of both methane and carbon dioxide with no ammonia, "would hint at an ocean interacting with the atmosphere," Scheucher, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Insider in an email.

"Based on what we know about how atmospheric chemistry operates, there is no other explanation," Madhusudhan, who led the team that first proposed Hycean worlds in 2021, said.

Still, Kempton is not so certain and said more modeling needs to be done to ensure that the signatures Webb observed could only come from an ocean.

Since the study of Hycean atmospheres is so new, it's possible that scientists haven't yet discovered other processes that could make the carbon dioxide and methane detected in K2-18 b's atmosphere.

"I'd want to see those kinds of studies really digging into: 'Is this a unique signature of a water ocean or not?' — because it's such an indirect argument — before I'd be really comfortable saying there's liquid water under there," Kempton told Insider.

If the ocean does exist, Madhusudhan said, there's a chance it would be too hot for life.

Correction: September 13, 2023 — An earlier version of this article misstated Doriann Blain's past affiliation. Blain is currently at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, but studied K2-18 b at a different scientific institution.

This story has been updated. It was originally published on September 12, 2023.

Insider science reporter Marianne Guenot contributed reporting to this story.

Read the original article on Business Insider

Yahoo News

Yahoo News