Astronomers spot ‘overweight’ planet that appears too big for tiny host star

Astronomers have spotted an “overweight” planet that appears to be far too massive for its petite host star.

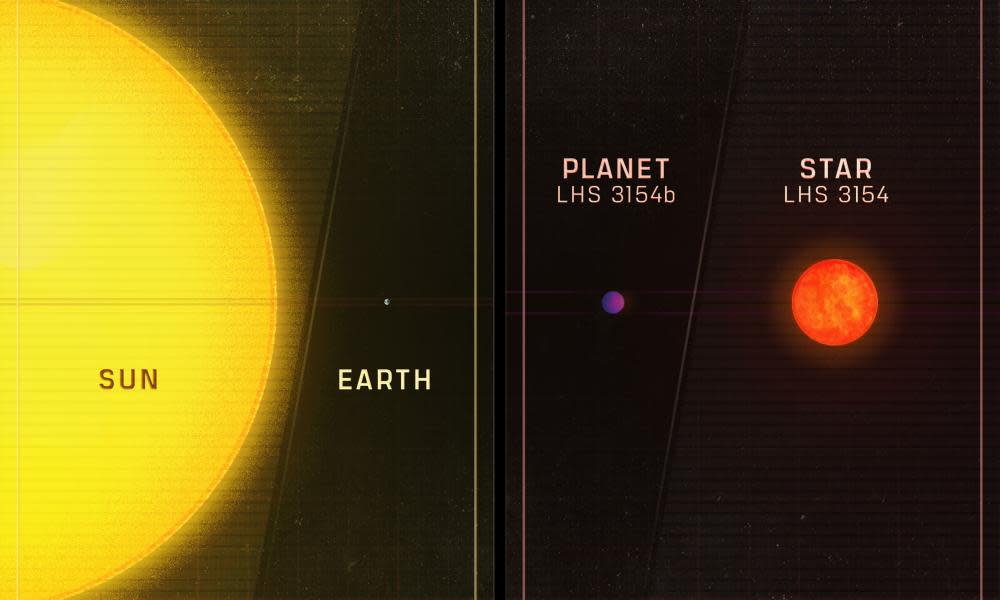

The planet, which is 13 times bigger than Earth, is orbiting a star called LHS 3154, which is nine times smaller than the sun. The planet’s heft is unremarkable in its own right, but its pairing with an ultracool dwarf star, the smallest and coldest stars in the universe, has puzzled scientists.

The unlikely pair have a mass ratio 100 times higher than that of the Earth and the sun and far in excess of the limit predicted by current theories of planet formation.

“This discovery really drives home the point of just how little we know about the universe,” said Prof Suvrath Mahadevan, of Penn State University and co-author of the research which is published in the journal Science. “We wouldn’t expect a planet this heavy around such a low-mass star to exist.”

Stars are formed from large clouds of gas and dust, which cool and collapse under their own gravity. As it rotates around the newly formed star, the remaining gas and dust flattens into a disk, a bit like dough being spun into a pizza. Eventually, the matter in the disk can clump together to form planets.

The amount of matter available for planet formation is thought to scale with the size of the host star.

“The planet-forming disk around the low-mass star LHS 3154 is not expected to have enough solid mass to make this planet,” Mahadevan said. “But it’s out there, so now we need to reexamine our understanding of how planets and stars form.”

The researchers spotted the oversized planet, named LHS 3154b, using an instrument called the Habitable Zone Planet Finder, or HPF, that detects tiny wobbles in the light of distant stars that indicates a planet in orbit.

The system was designed to detect planets orbiting the coolest stars outside our solar system with the potential for having liquid water – a prerequisite for life as we know it – on their surfaces.

While such planets are very difficult to detect around stars like our sun, the low temperature of ultracool stars means that planets capable of having liquid water on their surface are much closer to their star relative to Earth and the sun. Observations of LHS 3154 revealed it to be very close to its host star with an orbital period of just 3.7 days.

“Think about it like the star is a campfire. The more the fire cools down, the closer you’ll need to get to that fire to stay warm,” Mahadevan said. “The same is true for planets. If the star is colder, then a planet will need to be closer to that star if it is going to be warm enough to contain liquid water.”

In a commentary on the findings, Prof Frédéric Masset of the National Autonomous University of Mexico said that finding such a big planet in the vicinity of such a small star is “unheard of” and could prompt a rethink of planetary formation.

One explanation could be that planetary disks contain far more dust than previously thought.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News