Australia's Deepest Rifts Leave Indigenous Rights Vote in Peril

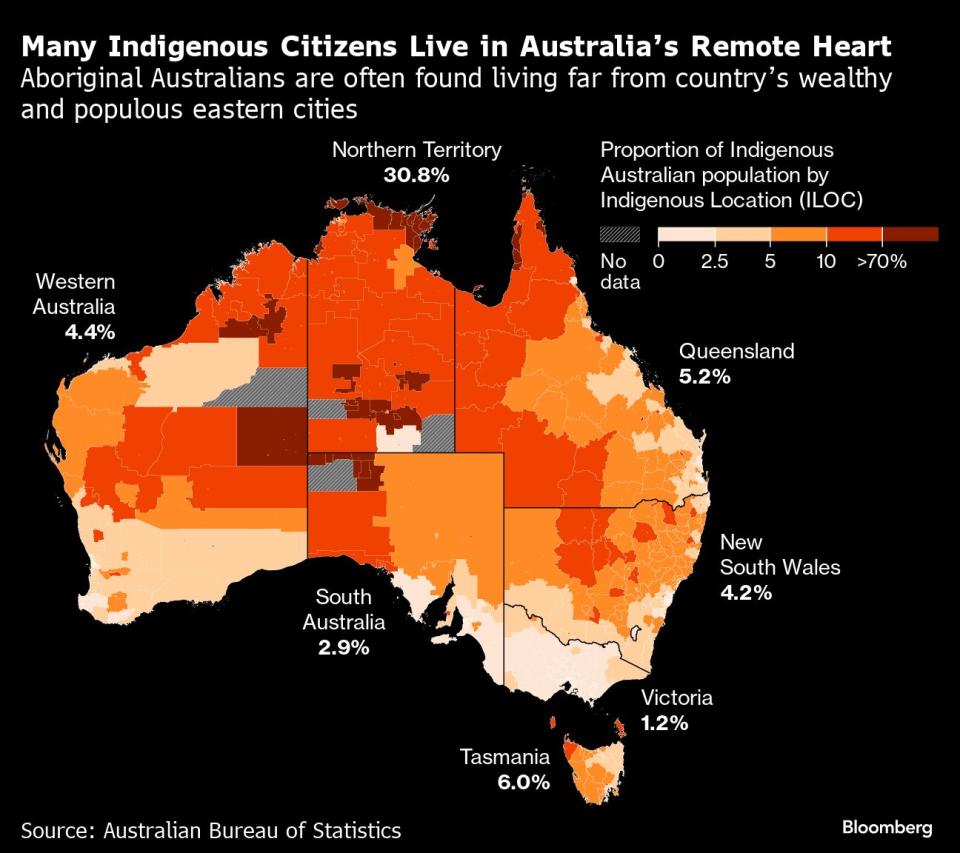

(Bloomberg) -- In one of the world’s richest nations, some remote townships experience living standards closer to the poorest places on Earth than to the rest of their country.

Most Read from Bloomberg

China Flags ‘Security Incidents’ With iPhones as Bans Expand

Luxury Cruise Ship Full of Australians Stuck in Greenland Arctic

iPhone Pro’s Titanium Finish Stands Out in First Look at Device

Aiming to reduce that gross inequality, Australia’s center-left Labor government has set a referendum for Oct. 14 proposing a constitutional change that would see the creation of an advisory body made up of Indigenous Australians to give lawmakers feedback on policies affecting their people. Known as the “Voice to Parliament,” the proposal is facing opposition both from center-right lawmakers — and from within the community that’s suffering.

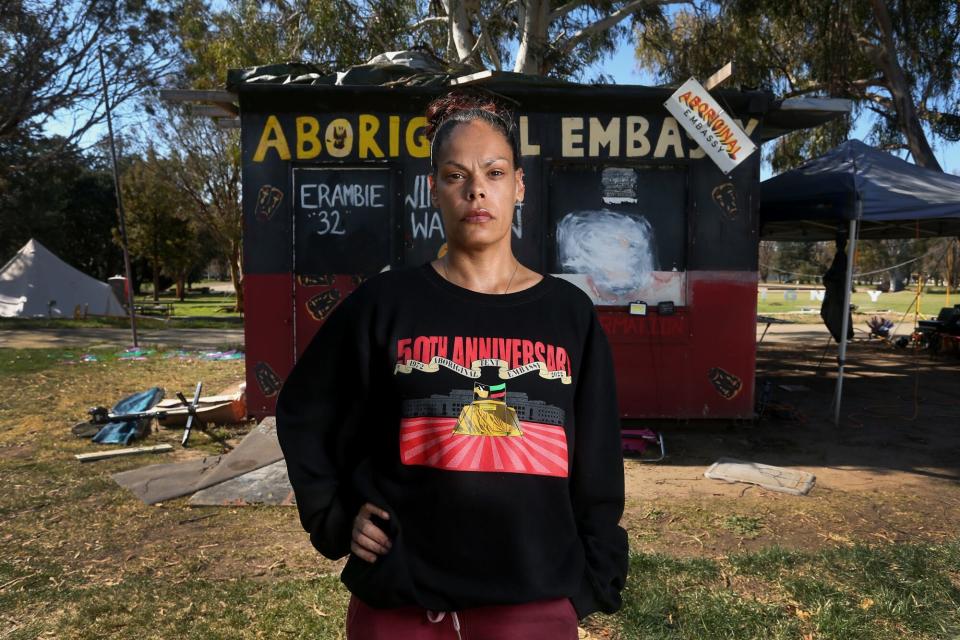

Just a couple of hundred meters from the nation’s Parliament, Malika Munro helps maintain the Indigenous Tent Embassy, which sprang up more than 50 years ago as a symbol of protest over European colonization. It’s a little more permanent these days — there are large tents, a couple of shipping containers and an old caravan that serve as offices for those like Munro who want to remind the rest of Australia, and indeed the world, of their peoples’ plight.

A Wiradjuri Gomeroi woman whose mother-in-law was forcibly removed from her parents to be raised by White Australians, Munro won’t be supporting the Voice. “It’s not going to fix any of the atrocities that have been imposed on our people,” she says. “You cannot fix a gunshot wound with a Band-Aid.”

About 2,500 kilometers north, right near the very tip of Australia, Wayne Butcher is mayor of the Indigenous township of Lockhart River. While he knows it won’t be a cure-all, Butcher will be voting “Yes.” With a mix of indignation and resignation he recounts the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Indigenous woman, another who died of a burst appendix and another from complications related to her diabetes.

“We can’t keep doing the things we’re doing,” he says, detailing how seven of the last 10 women to die in his community were below the age of 45. “Something’s broken here.”

Butcher and Munro’s different views illustrate the split within the Indigenous community between those hopeful the Voice will play a part in improving the lives of Australia’s almost 1 million Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders and those who reject it as a hollow gesture — or worse, a con.

There’s a similar division within the broader population, with opinion polls suggesting the vote for the Voice will end in a “No.” Backers including Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and companies including Qantas Airways Ltd. — which has adorned three of its aircraft with the official Yes23 logo — are hoping they can turn that around in coming weeks and convince a majority of voters in a majority of states to support it.

The center-right Liberal and National parties oppose the referendum. With their support, the “No” campaign has aired concerns about the lack of detail over the Voice — it’s not clear who would be on the panel, how they’d be selected and how far its remit would extend — and characterized what would be the biggest change to the constitution in at least half a century as vague and risky.

The “No” camp has warned of lengthy legal challenges and government dysfunction if the new untested advisory body is written into the constitution. Since the beginning of the year, the government has been criticized for failing to provide more information on what the Voice might look like, with some commentators arguing the lack of detail has pushed some Australians on the fence about the proposal to turn against it.

Facing a concerted push from the “No” camps, polling has shown a dramatic drop in support for the Voice. In February, a survey by Newspoll found 56% of Australians supported the change, with 37% against; by September, the number had flipped — the “No” vote was at 53%, with 38% for “Yes.”

Read More: Why Australia Plans to Vote on an Indigenous ‘Voice’: QuickTake

The stakes for Albanese are high. He’s invested huge personal political capital in the proposal — it was the first thing he mentioned in a victory speech following his election win in May 2022. Now, as support for the Voice has ebbed, the Liberal National Coalition has overtaken Labor on primary votes for the first time since last year’s election, according to the latest Newspoll survey.

That division has affected corporate Australia too. Qantas and supermarket chain Woolworths Group Ltd. have been vocal in their favor of the proposal. But the group’s homeware chain, Big W, recently pulled its in-store announcements in support of the vote after a backlash from shoppers.

Indigenous Australians have one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world, with evidence of habitation in the country dating back more than 50,000 years. Since British colonization began in 1788, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have faced mass killings, dispossession of their land and the introduction of new diseases that ravaged their population.Now, despite living in one of the wealthiest countries in the world, Indigenous Australians have a life expectancy about 10 years shorter than the rest of the population, are vastly more likely to find themselves in prison and suffer from diseases that have been eliminated in most developed nations, such as rheumatic heart disease.

Starting in 2009, the Australian government began to release annual “Closing the Gap” reports to highlight the gulf between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and the rest of the country. Almost 15 years after they began, some metrics have barely progressed and others have even gone backwards.

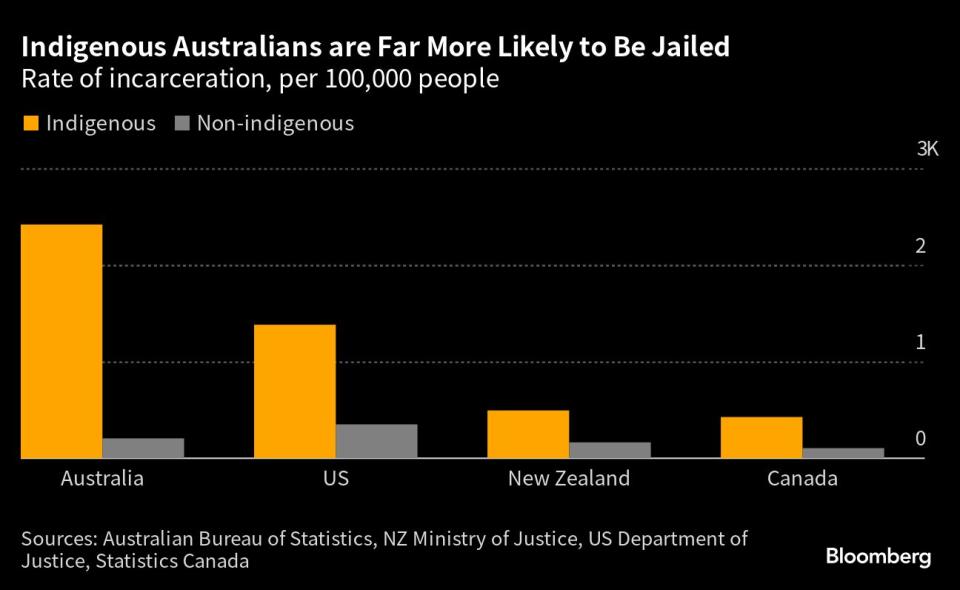

On most measures, Indigenous Australians’ quality of life is worse than other First Nation peoples in former British colonies, such as Canada, New Zealand and the US. No former British colony has achieved equality between its original inhabitants and the rest of the population, however Australia’s gap is staggering.

New Zealand, Canada and the US all have high incarceration rates for their Indigenous populations, but none are even close to the ratio for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, who are eleven times more likely to be jailed than the national average.

The income gap between the Maori population and the rest of New Zealand is about $100 dollars every week, based on median income data. It’s a little less in Canada. Indigenous Australians earn more than $300 less a week compared to other Australian citizens.

Australia is the only former British colony which doesn’t mention the country’s Indigenous population in its constitution.

The drive for recognition of Australia’s Indigenous people in the country’s constitution dates back decades. As momentum for the change grew, in May 2017 there was a gathering of more than 240 Indigenous elders at Uluru, the huge red sandstone rock in the heart of Australia. After four days of talks, the elders agreed on what they saw as the pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ rights going forward.

Known as the “Uluru Statement from the Heart,” it called for three things: a treaty, a truth-telling commission and a First Nations Voice to Parliament, enshrined in the constitution.

Albanese promised if he became prime minister he would enact the three reforms — treaty, truth and voice. A “No” vote on the Voice would likely scupper prospects to advance on the other two fronts.

Speaking to Bloomberg in the red dirt of the Northern Territory, Butcher said the Voice referendum shouldn’t be seen as a political debate, but rather a “moral question.” An Indigenous man from the Uutaalnganu people, Butcher said a body like the Voice could help prioritize funding to where it would have the most impact.

“You look at the investment in health in the Cape and Torres Strait, there’s nearly a half a billion dollars invested. Why are people dying young? Something’s wrong here,” he said.

Indigenous Australians who oppose the Voice would agree there’s something gravely wrong. But the Voice isn’t the answer, they argue.

Malika Munro and her cousin Nioka Coe’s parents were among the founders of the Tent Embassy in the 1970s and now they’re carrying on the tradition, surrounded by signs which proclaim “Sovereignty” and “No to the Voice.” A black, yellow and red Aboriginal flag is perpetually at half-mast — a reminder of the hardships endured by their community.

“Our people are suffering in our own country,” Coe said. “Look at the stats, look at the suicide rates.”

Munro and Coe don’t want to align themselves with the “No” campaign being run by conservatives, but they certainly don’t support the Voice either. Neither trusts the government, saying they want to see a peace treaty and a commission to examine past atrocities.

Indigenous lawyer Taylah Gray grew up in the small NSW city of Dubbo, where she remembers being surrounded by a community who loved and supported her. But Gray also remembers her father being singled out by a security guard at the local grocery store — for no reason other than that he was a First Nations man.

Racism has long been part of everyday life for Indigenous Australians, but since the announcement of the Voice to Parliament campaign, many say it has gotten worse.

“We’re feeing the wrath of it,” says Gray, a Wiradjuri woman who didn’t say exactly how she was planning to vote on the Voice referendum. She paraphrased US civil rights icon Malcolm X: “You have to be very careful when introducing the truth to a nation who has never previously heard the truth about itself.”

Woolworths, which owns Australia’s largest supermarket chain, has discovered that public tolerance for corporate involvement in the debate has its limits. In early July, it started broadcasting support through in-store announcements across its Big W discount-retail network.

“We reaffirm our support for the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and its calls for a First Nations Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution,” Big W told shoppers hunting for bargain T-shirts and electric kettles. The sentence was pulled after customers complained.

“We recognize and respect our team and customers have varying views and perspectives,” Woolworths, which employs about 200,000 staff, said in a statement. The company’s support for the Voice, using the same words as the retracted Big W announcement, is still on its corporate website.

Former Qantas Chief Executive Officer Alan Joyce said there’s sound commercial sense to backing the Voice. “We think it’s the right thing to do, but we also think it’s good for business,” he said Aug. 24 after announcing record profits. Companies that are engaged in social issues appeal more to staff, potential employees, customers and shareholders, he said.With the mining-heavy state of Western Australia expected to be one of the key battlegrounds in the Voice campaign, both the “Yes” and “No” camps have been courting tycoon Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest. As yet, he has resisted calls to publicly take a side, irritating both camps.

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz, a board member at Macquarie Group Ltd. and Rio Tinto Plc., said that publicly supporting the Voice is a complex decision for companies because the issue has become so politicized and businesses don’t want to be seen to be taking sides. But Lloyd-Hurwitz, who personally supports the “Yes” campaign, said she believes investors care about how companies are dealing with social issues.

“If it’s a ‘No,’ that’s a national shame,” she said in an interview. “There is a focus from investors on companies and their efforts towards supporting Indigenous Australians.”

Shortly after coming to power in May 2022, the government appointed the world’s first Ambassador for First Nations People, Justin Mohamed. A Gooreng Gooreng man from Bundaberg in Queensland, Mohamed attended his first Garma festival in the role in 2023. Mohamed has to remain largely above the politics of the Voice given his diplomatic role, but he worries a “No” vote would risk tarnishing Australia’s reputation.

“It’s a bit like being hit with something in the stomach, and your breath’s gone,” he said. “And then you’ve got to pick yourself up and move again.”

--With assistance from Swati Pandey, Angus Whitley, Nabila Ahmed and Adrian Leung.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

ADHD Drug Shortages Worsen as Makers Say Production Is Maxed Out

James Dolan’s $2.3 Billion Sphere Is Raising Eyebrows—in a Good Way

Huawei’s Surprise Phone Gives Ammo to Biden Doubters on China

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News