‘On best behaviour, he was a joy’: the lost archive of English pop eccentric Vivian Stanshall

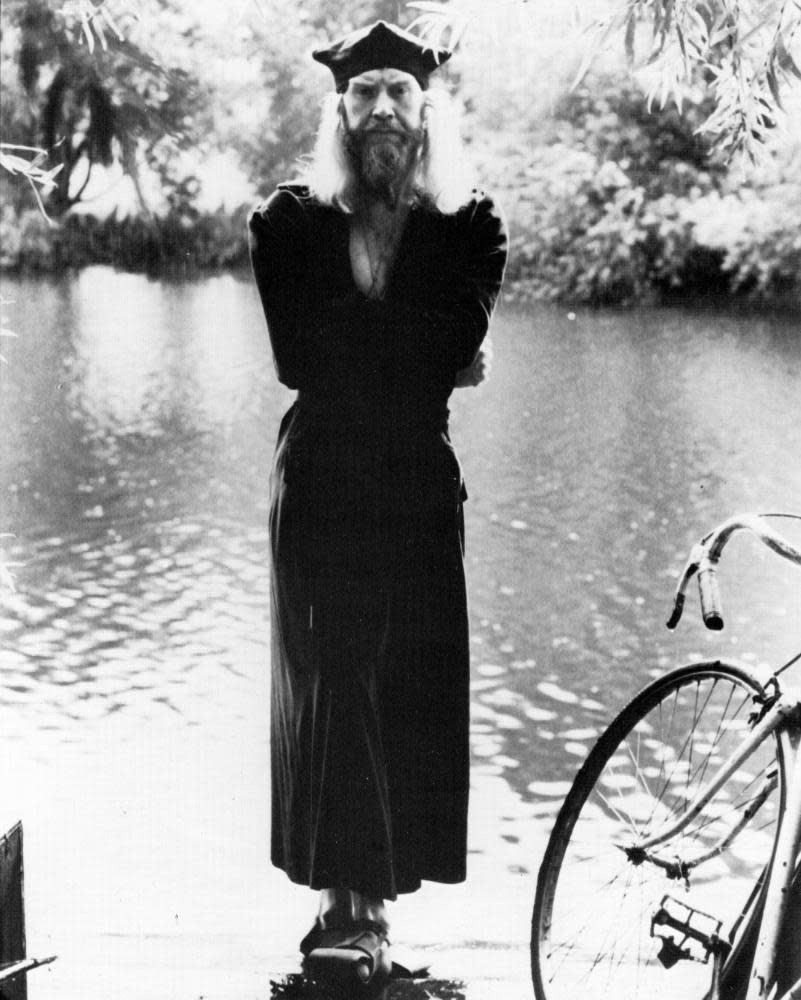

When Vivian Stanshall was found dead on the morning of 6 March 1995, after a fire in his top-floor flat in Muswell Hill, north London, he left behind a grand creative legacy and a whole heap of chaos. At just 51 years of age, yet with the disorderly, mythic bearing of someone many thousands of years older, this orotund, ginger-locked behemoth departed the world having refashioned the postwar vision of the English eccentric and irreversibly altered the path of British culture.

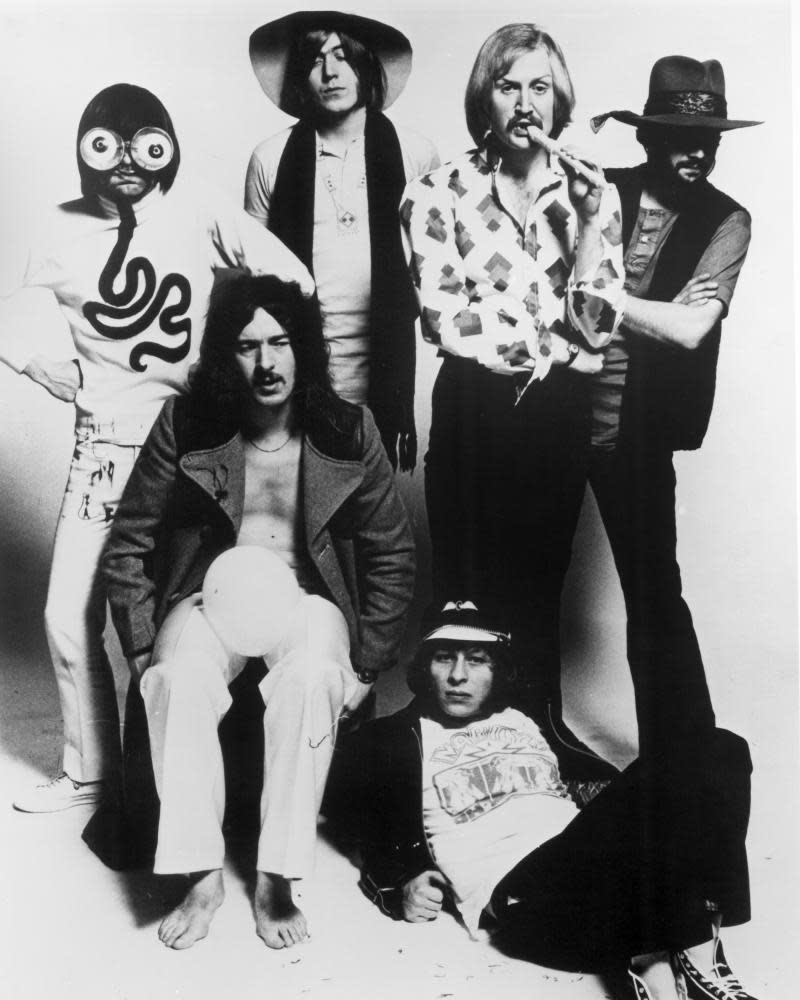

While his florid, stentorian contributions to Dadaist 60s trad-jazz mutilators the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band influenced everyone from the Beatles to Monty Python, a peripatetic path through the 70s saw him appear as the Master of Ceremonies on Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and as a regular lyricist for Steve Winwood, while his 1978 solo LP, the grandiloquent, gothic spoken-word masterpiece that was Sir Henry at Rawlinson End found lifelong fans in both Jarvis Cocker and Stephen Fry, who declared Stanshall “one of the most talented and magnificent Englishmen ever to have drawn breath”.

Yet a lifetime of anxiety, Valium addiction, alcoholism and mental illness had also left behind scorched friendships, broken engagements and a wealth of unfinished music for Warner Music, contained in boxes of two-inch tapes that sat for years in the airing cupboard of his son, Rupert, like some dusty, unsubtle metaphor. “The division of his estate after his death slaughtered me,” says 55-year-old Rupert Stanshall today, talking from his home in Watford. “Very expensive, very traumatic. Luckily, Warners said we could have Viv’s unfinished recordings and they didn’t want their money back. His late wife, Pamela, wanted to flog them. I didn’t.”

The majority of the recordings in Rupert’s possession were from the late 80s and early 90s, when Vivian and Pamela had split up and Stanshall Sr found a new creative spurt: recording Rawlinson End sessions for John Peel, landing choice advert work and playing live again with various trusted musician friends from the 70s including old Bonzo Dog associates Roger Ruskin Spear, Neil Innes and Rodney Slater. He had also been commissioned by Warners chairman and No 1 Viv fan Rob Dickins, and was developing three new albums: two further Rawlinson End instalments and a studio LP entitled DoG NeW TrickS.

“He was still incredibly creative in those years, but it wasn’t consistent,” says Slater. “There would be days, weeks, when he was just like a jellyfish, straight on the vodka and orange from the moment he got up. Then, suddenly, a major incident like a trip to the Priory or his split from Pamela might allow him to to focus.”

However, when the tapes were eventually retrieved from Warners in the wake of Vivian’s death, the promise that they might contain complete works was not to be. “I listened to them and, Christ, it was difficult,” says Slater. “They were just bits and pieces, fragments. I was crushed.”

At the behest of Rupert Stanshall, the task of restoration initially fell to Vivian’s friend and music arranger John “Meggo” Megginson. Megginson also had plans for a grand memorial concert, a chance to capitalise on Stanshall’s legacy with the Beatles, Python, Oldfield and Winwood, as well as the tributes paid to the man by superfans such as Peel, Fry, Jarvis Cocker, Adrian Edmondson and Paul Merton. However, plans for the concert, art exhibitions and and lyric anthologies all fell by the wayside. As Megginson began his own battle with alcoholism, the promise of the tapes also faded.

In summer 2010, Rupert Stanshall received a DVD from Merseyside actor Michael Livesley, containing a recording of a one-man show Livesley had just done at Liverpool’s Unity Theatre – the first-ever stage production of Sir Henry at Rawlinson End. Speaking all the character voices himself, Livesley turned Stanshall’s absurdly loquacious musical play-for-voices into a joyous live experience, dancing across a dilapidated drawing-room set, sporting a deerstalker, plus-fours, a houndstooth overcoat and red-and-green stockings, while a dinner-jacketed band replicated Stanshall’s wheezing, arthritic music on double bass, violin, banjolele, jaw harp and spoons.

“I’d grown protective of dad over the years because I’d been through the dark ages with him,” says Rupert. “Emotionally it sucks it out of you, but I also felt the need to look after him. I watched Mike’s DVD and thought, ‘Right, I trust this guy, I’m going to get him involved.’ It was cathartic.”

Rupert wasn’t the only one. When Livesley’s production moved to London in October 2011, it drew praise from Bonzos co-founder Neil Innes. In 2013, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of Vivian’s birth, Rupert and Neil organised a grand performance of Rawlinson End at London’s Bloomsbury theatre, with Livesley joined by most surviving Bonzos members, Rick Wakeman and esteemed folk bassist Danny Thompson. “Neil asked me to sing with the reformed Bonzos,” says Livesley. “We did a tour, then we were booked to do another tour. Then the legal shit kicked off.”

In 2015, the group’s former manager Robert Carruthers trademarked the band’s name, preventing the surviving members from performing under it. What could have signalled the end of everything instead marked the beginning of a new chapter. Label boss and band manager Richard Allen, a longtime Bonzos aficionado with significant legal experience, helped secure a high court victory ruling that the trademark was registered in bad faith, and in the process released the Stanshall tapes from their own legal minefield. “Around 2010, Meggo tried to flog the tapes,” says Allen. “It all got quite acrimonious, so I spoke to all the parties, worked out what the hell was going on and an agreement was reached whereby the Bonzo reissues label Snapper became guardians of Viv’s archive.”

At the behest of Rupert Stanshall, Livesley was brought in to edit the Rawlinson recordings, a task the actor describes with some self-deprecation as “editing out all the farts, burps, fluffs and fags”, but which in reality involved seven months of meticulous resurrection, assembling numerous disparate tapes and fragments into a narratively coherent Stanshallian experience.

Simultaneously, the job of restoring DoG NeW TrickS – renamed Dog Howl in Tune after a specific Stanshall composition – fell to producer and musician Andy Frizell, who had previously collaborated with Vivian in 1994. “He was fascinating to be around,” says Frizell. “An incredible intellect, very inspiring and totally driven. He wanted to do a new Sir Henry album, but also another album of new songs. The more time I spent with him, the more boyishly excited he was. I should add he wasn’t drinking at the time.”

Given how much chaos surrounded Stanshall in his final years, it’s surprising and encouraging to hear these tales of positive creativity. Mekons violinist Susie Honeyman, who knew and played with Stanshall from 1983, has a theory: “I think it was because he had huge respect for musicians, especially anyone who could read music. He was quite an alarming figure when I first met him – naked chest, cape, swimming trunks – but you couldn’t help [but] be attracted to him. He was so charming and articulate. But I also saw the insecurity and vulnerability. His first wife, Monica, Rodney [Slater], Meggo and [minder and sometime Bonzos drummer] Glen Colson looked after him, kept him together.”

Related: ‘The god of hellfire returns!’ Can Arthur Brown incinerate Covid?

“On best behaviour, he was just a joy,” Colson agrees. “But don’t be fooled. Boozed up, drugged up, he was a nightmare. And being so witty he’d scare the shit out of you. He’d lie in bed drinking booze for weeks on end. I’d go round to his flat, clean his bed out, throw the booze down the sink, stick him in the bath, pour a bit of Dettol in there, disinfect him and we’d go through his post. There’d be cheques, money, hundreds of unanswered work offers from everybody, but as soon as he had the money, he’d go back on the piss again, so it became impossible.”

“Maybe if I had recorded more with him I’d have seen that other side,” admits Frizell. “One thing I discovered from working on this last batch of songs is that he was really aware he’d treated people badly. A lot of the songs are about trying to make it up to them.”

Immersed in the process, Frizell began sorting through hundreds of tapes and cassettes: “Stuff with crappy drum machine, 90s Midi bass and horrible digital strings. Then backing tracks by people like [Cream bassist] Jack Bruce or [late, great British session guitarist] Ollie Halsall. I added in drums, bass, guitar, sometimes brass and wind instruments. I tried to imagine I was talking to Viv. There were takes where he was obviously not in a very good state, but the desire was to do right by the memory of the man, to treat him with respect.”

However, here was a man who, in his lifetime, was famous for such moments of engineered high surrealism as dressing as a polar bear to go shopping in East Finchley (and politely asking the grocer for “penguins”) or faking heart attacks on London’s Oxford Street while dressed as a vicar. Perhaps somewhat inevitably, a curious air of Stanshallian surrealism took over proceedings.

“A load of music from the sessions was initially missing,” says Allen. “We found one big chunk from the Sir Henry sessions when Jon Street from the Vivian Stanshall Appreciation Society contacted us to say that one of his members had found a cassette marked ‘Ruddles/Sir Henry’ at the bottom of a filing cabinet purchased from an advertising agency.” Then they were sent tapes belonging to Bonzos and Stanshall guitarist Anthony “Bubs” White. “When [White] died in 2013, all of his personal effects ended up in the hands of some friends in Cambridge,” says Allen. “We only found out about them because they had a flood in their house last Christmas, and moved all the tapes on to the street. This guy over the road saw Vivian’s name on them and called us.”

The finished LPs will be released on 14 July, 27 years after Stanshall’s death. Incredibly, there is still more to come. There are plans for another album of “wilder, crazier stuff”, plus a box set of outtakes, BBC sessions, a live concert and a lost Shackleton musical. “It’s been quite a revelation for me,” says Allen. “He was living a fairly chaotic and disturbed life at the end, and obviously inflicted all kinds of things on people around him. But this is the flipside, isn’t it? This is the good stuff. Maybe this is the beginning of a Vivian Stanshall renaissance.”

However, for one man, the unlocking of Vivian Stanshall’s archive is very much an ending, and a happy one at that. “In the past I’ve described his legacy as this thing on my shoulders which just got heavier and heavier,” says Rupert Stanshall, with an audible sigh of relief. “But I listen to these finished albums and I’m ecstatic. I feel like the Ancient Mariner. The albatross lifted and flew away.”

• Dog Howl in Tune and Rawlinson’s End are released via Madfish Music on 14 July

Yahoo News

Yahoo News