If Biden Drops Out, What Happens to His Money?

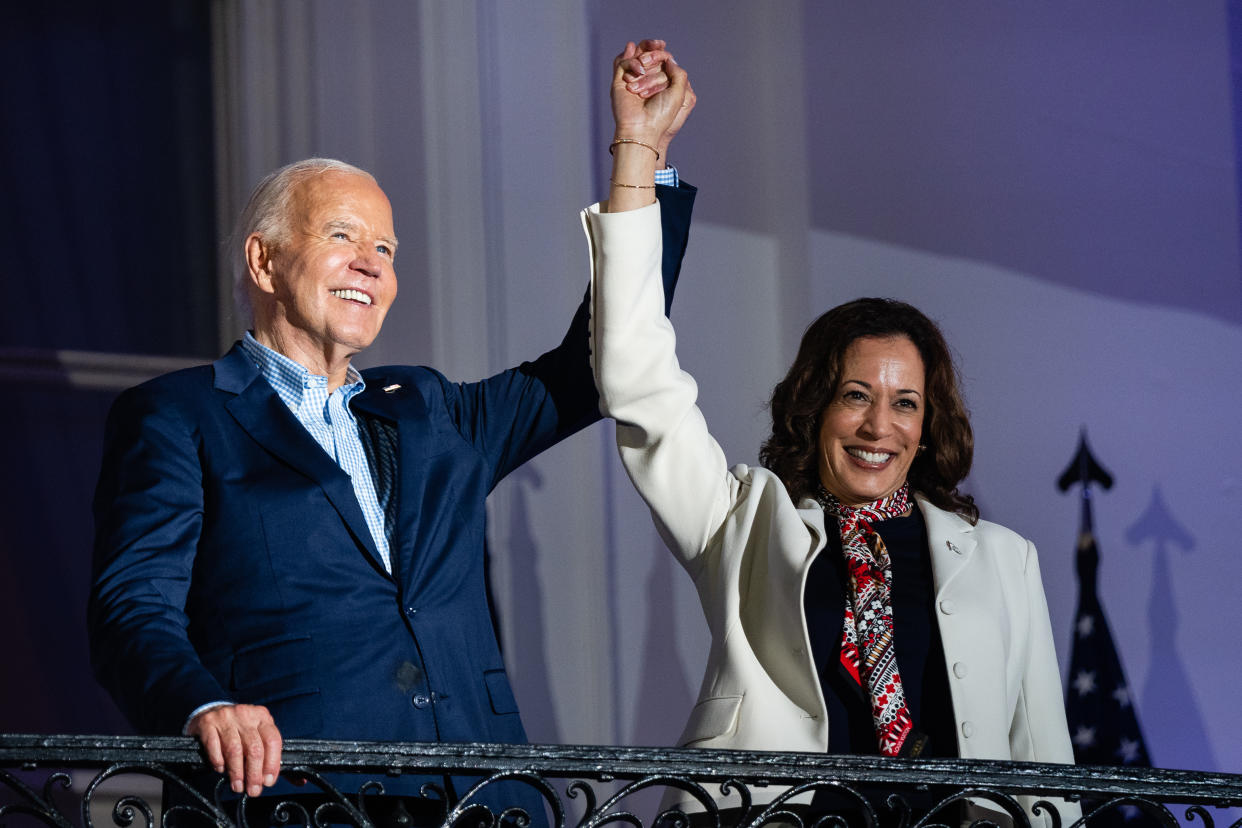

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden forcefully says he isn’t withdrawing from the presidential race. But if he does, there’s a reason or two that many leaders of his party think the next nominee would be Vice President Kamala Harris.

There’s the built-in Democratic base. There’s the easier logistics. There’s the history to be made.

And yes, there’s the money.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

If Democrats carried out a stunning switch at the top of their ticket, what happens next would have no modern precedent — including in the campaign finance realm. But we do know a few things:

Harris would have a $91 million (or so) edge.

Over the last two years, Biden and Harris have together raised hundreds of millions of dollars for their reelection bid. That money has been split across the Biden campaign, the Democratic National Committee, almost every state Democratic Party, and various joint-fundraising committees that cycle cash among all of those entities.

As of June 30, all of those groups had about $240 million in cash on hand. Most of that money — say, the stockpile at the Democratic National Committee — wouldn’t be affected by a change of nominee.

But the most important money is in the accounts held by the Biden-Harris campaign committee: $91 million as of May 30. (The campaign hasn’t disclosed how much it had as of June 30.) That money has been raised by the Biden-Harris ticket, and belongs to the Biden-Harris ticket. The only people whom that money follows are, you guessed it, Biden and Harris.

So if Biden were to cede his role and Harris were to be officially nominated (with a new No. 2), her new ticket would have almost no interruption financially. She would have immediate access to the $91 million or so in cash on hand, an important consideration given how former President Donald Trump and Republicans have rapidly caught up to the Democrats in fundraising.

Whitmer, Newsom or someone else would be more complicated.

What if the new nominee were not Harris, but someone like Gov. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan or Gov. Gavin Newsom of California?

In that case, almost all of the $91 million in the campaign account would have to be refunded to donors, a pretty remote outcome. (One caveat: The money that is designated for the primary election, as opposed to the general election, could be used by anybody up until the Democratic National Convention next month.)

But there is a catch, one that has been informed by recent precedent. If someone other than Harris were to lead the ticket, the Biden-Harris campaign could certainly transfer that $91 million to a federal super political action committee, which could spend it on advertising for the new Democratic ticket.

That would be suboptimal, because money at an outside group can’t be controlled directly by the campaign, and super PACs have to pay higher rates for advertising time. But the money would not go to total waste.

There is, however, an alternative way for a new, non-Harris presidential candidate to benefit from the money in the campaign account, one that savvy Democrats would almost certainly explore.

When Michael Bloomberg withdrew from the 2020 Democratic presidential primary race, his campaign account had $18 million or so left over. He was eventually able to transfer all of that money directly to the Democratic National Committee.

That $18 million well exceeded the contribution limits for individual donors, and Bloomberg’s transfer was controversial because his presidential campaign was almost entirely self-funded.

While federal campaigns can send leftover money to whatever group they want in unlimited amounts, critics argued that Bloomberg’s transfer had essentially allowed someone to avoid contribution limits by (briefly) running for president. Campaign-finance watchdogs cried foul, but the Federal Election Commission last year effectively blessed the move.

That precedent could be instructive here. Perhaps the Democrats would try to transfer that $91 million directly to the DNC — making for a cash-flush party committee that could make up for the fact that an entirely new candidate’s campaign would start at pretty close to $0.

A billionaire like J.B. Pritzker could be a white knight.

If the nominee is not Biden or Harris, there is one way that the Democratic ticket might not start from zilch. In that scenario, the smartest thing financially for Democrats might be to turn to a billionaire who could turn that zero into, well, a big number followed by a bunch of zeros.

Take someone like Gov. J.B. Pritzker of Illinois. The heir to the Hyatt hotel fortune, he spent $350 million on his two campaigns for governor, and he would theoretically be able to, by writing a check, put much more than $91 million into a presidential campaign.

Self-funders do not face contribution limits. And so choosing one might allow a new Democratic presidential campaign to achieve some parity with Trump almost immediately.

If Democrats do reopen their nominating contest to a wider group of hopefuls, it would be rather remarkable to see independently wealthy contenders boasting about their net worths. But their fortunes would, without a doubt, be a political asset.

Small donors are an X-factor.

One wild card to all of this is how one very important type of donor — the small ones — would respond to a Democratic presidential upheaval.

To hear some opponents of Biden tell it, his removal from the ticket would create mounds of excitement that encouraged small donors, and some big donors, too, to support a campaign led by a younger Democrat, up to the $3,300 individual limit.

A new nominee would indeed be exciting for many Democrats. But it could also plausibly be terrifying.

Could Democratic digital fundraising slump during a period of profound uncertainty? What would happen if the new nominee proved even less competitive than Biden, who, for all his flaws, has a digital fundraising operation that has been hauling in money for five years now?

For Democrats, there are no easy answers. Just plenty of questions.

c.2024 The New York Times Company

Yahoo News

Yahoo News