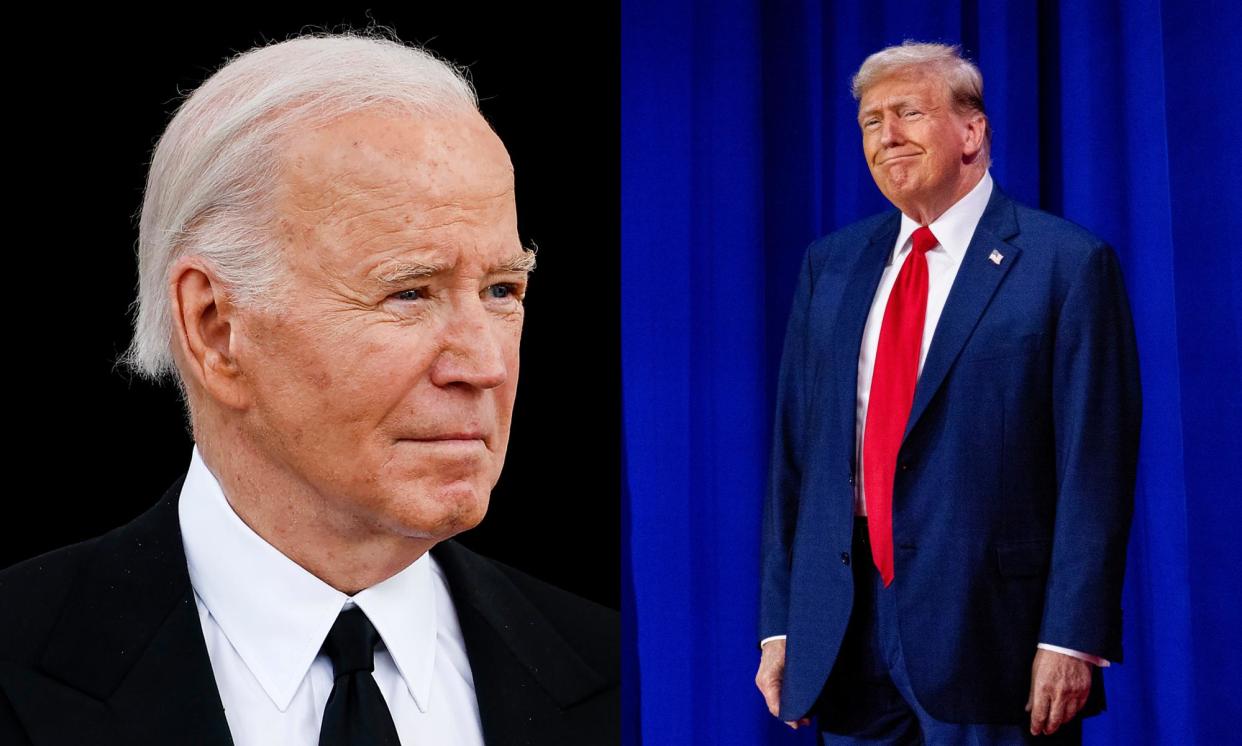

Biden v Trump II: a rematch with few historical precedents

When Joe Biden and Donald Trump secured enough delegates to lead the Democratic and Republican party presidential tickets in November, they confirmed what many voters expected but fewer actually wanted: a redo of the 2020 election.

Republicans skeptical about giving Trump a second shot tried in vain to elevate a viable primary opponent. Powerful donors, including the Koch-aligned Americans for Prosperity Action, poured money into former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley’s campaign, but Haley was unable to claw enough support away from Trump to pose a threat to the former president.

So for the first time in more than 50 years, the Republican party will rerun a candidate who already lost a general presidential election – the last time that happened was in 1968, when Richard Nixon, who had lost the 1960 general presidential election, ran again and won.

It has been even longer since a presidential candidate faced a true rematch.

When was the last presidential rematch?

The last time Americans voted in a contest between the same two presidential candidates as the election before was in 1956, when the Republican Dwight Eisenhower and the Democrat Adlai Stevenson faced off for the second time in four years.

Eisenhower, a former military officer famed for his triumph as a second world war general, beat the Stevenson, who was known as cerebral and humorless (“Eisenhower a Typical Man of Action And Stevenson a Man of Thought,” read a 1952 New York Times headline), in a landslide in 1952.

During his first term, Eisenhower, an anti-communist, backed the regime changes in Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954 – replacing elected leaders with authoritarian regimes. The same year, he signed the Communist Control Act, which made the Communist party illegal in the United States, calling it a “conspiracy dedicated to the violent overthrow of our entire form of government”.

On domestic economic issues, he governed as a moderate, expanding social security benefits to millions of people and creating the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (later renamed the Department of Health and Human Services).

By the end of his first term, Eisenhower had grown elderly but remained popular.

Stevenson scraped by in the Democratic primary but lost resoundingly in the 1956 general election by an even wider margin than the first time around, with Eisenhower winning more than 57% of the vote, 457 electoral college votes and all but seven of the states.

What about an ex-president, like Trump, running against an incumbent?

“If [Trump] were to win, he would be the only one since Grover Cleveland to actually get back to the presidency after losing it,” said Jeff Pasley, a professor of American history at the University of Missouri.

Elected in 1884, Cleveland was the first Democrat to win the presidency after the civil war. The former New York governor had crusaded against corruption in politics and was active in the economically conservative, pro-business “Bourbon Democrat” movement.

In the lead-up to the election, Cleveland’s supporters lobbed allegations of corruption against his opponent James Blaine, questioning Blaine’s financial dealings with railroad companies.

Republicans, in turn, hammered on allegations that Cleveland had secretly fathered a child during an illicit affair with a waitress – their respective alleged moral failings became central to the 1884 campaign.

The personal attacks ignored a deeper, fundamental moral corruption in American politics and society.

As historian Henry Graff observed in his biography of Cleveland, the president’s first campaign took place amid Jim Crow and the backlash to Reconstruction-era policies granting equal rights to Black Americans: “[R]acism was rampant in the country” with formerly enslaved Americans facing “discrimination and segregation and, increasingly in the South, lynching”, while the genocidal conquest of Indigenous lands continued into the end of the 19th century.

“The campaign,” wrote Graff, “avoided these pressing and shameful matters.”

Cleveland won the popular vote narrowly and picked up 37 more electoral votes than Blaine.

During his first term, Cleveland advocated for, but ultimately failed to enact tariff reform – a key issue of his first campaign. He viewed his post as president as an administrative one and was reluctant to act forcefully.

He ran for re-election in 1888 against the Republican Benjamin Harrison, narrowly winning the popular vote but losing the electoral vote resoundingly.

Determined to hold office again, Cleveland decided to run for president in the 1892 cycle, campaigning again in opposition to tariff hikes.

A few important things had changed in the four years that Cleveland was out of office.

The Populist party, which advocated an eight-hour workday and benefits for veterans, was drawing increasing support from the Republican voters who prioritized those issues.

Meanwhile, Harrison’s wife, Caroline Harrison, was dying of tuberculosis.

During Caroline’s illness, Harrison had refrained from campaigning, and when she died two weeks before the election, the other candidates stopped campaigning out of respect, too. Cleveland won by a wide margin in both the popular vote and electoral college, making him the only president to come back and win after losing to the same candidate four years earlier.

What lessons can Cleveland’s non-consecutive presidencies teach us about Biden v Trump?

Cleveland’s example shows it’s possible for an ex-president to claw the office back after losing it to the same opponent. But it’s also a tricky comparison: Cleveland was, according to Graff, “the very symbol of rectitude and incorruptibility” and didn’t face a barrage of criminal indictments or a well-coordinated opposition campaign like Biden’s.

Meanwhile, his supporters may have agreed with him on economic issues, but they were hardly fanatics.

“Cleveland had fans but it wasn’t like there was a Cleveland cult,” said Pasley. “He just happened to be the last successful Democratic president.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News