‘It’s our biggest employer’: How a lucrative war in Yemen fuels conflict in Darfur 2,000km away

You can earn more money fighting in Yemen for six months than in a lifetime.

This adage rages through the streets of Darfur, Sudan’s conflict-ridden western region, where a ruinous war more than 2,000km away in Yemen has become the country’s “biggest local employer”.

Everyone knows someone who has signed up.

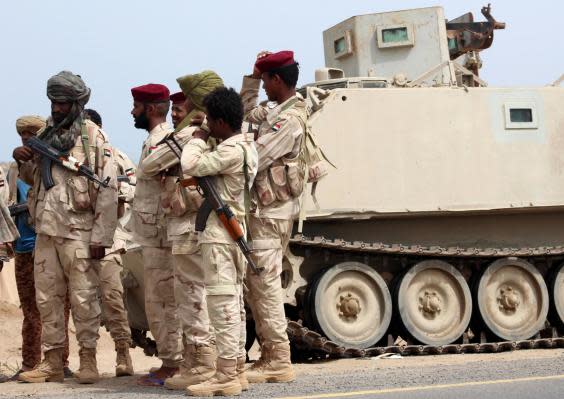

For nearly five years the Gulf has hired members of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a feared paramilitary group, and the Sudanese military to fight alongside Yemeni government troops against the Iran-backed Houthi rebels.

And so, despite the dangers, the promises of unimaginable riches have driven tens of thousands of Darfur’s men, and boys, to the RSF’s recruitment centres.

For a six-month deployment, RSF foot soldiers, who often hail from the poorest segments of society, can earn a million Sudanese pounds (around £17,000) – more money than they could ever hope to gather in a lifetime. Officers make double that.

In Sudan, the minimum wage across the country is just $190 a month, but for farmers and goat herders it is considerably less.

But residents now say five years of wealthy, armed and trained fighters returning from Yemen has only ratcheted up tensions in Darfur, a region that has been ripped apart by at least 16 years of civil conflict.

Many also fear that it has unnaturally swelled the ranks of the feared RSF, which is accused by rights groups of committing genocidal violence there.

“The war in Yemen has been the biggest employer in Darfur and is the main way out of poverty for the youth,” said one RSF captain, who returned from fighting in southwest Yemen at the start of the year.

He asked to remain anonymous, fearing backlash for speaking out.

“It’s impossible to earn one million [Sudanese] pounds ever in your wildest dreams. It’s purely economic. Sudanese people wouldn’t be willing to go and fight in a completely different country for a cause they know nothing about,” he added.

The father of four spoke at his home in North Darfur’s regional capital El-Fasher, while battling malaria, which he had not been able to shake since coming home.

An unprecedented outbreak of malaria and dengue fever in North Darfur over the last two months has fuelled rumours that the massive quantity of soldiers returning from Yemen brought the diseases with them.

The captain said people had become so eager to make money that when a recruitment cycle opens, the centres receive 10 times the number of applications than the available places.

Once signed up they go through sometimes as little as three months training before being sent to the front.

“Families have been afraid to send their children to school because they were worried about their sons running off to sign up because it can set you up for life,” he continued, shivering.

“Others actively want their youth to go. You send two sons and the entire family is sorted forever.”

At its peak between 2016- 2017, more than 40,000 Sudanese troops were believed to be fighting in some capacity in Yemen’s war, either within the country or along the border with Saudi Arabia.

The turnover is high and so tens of thousands of men have gone through the process. It is believed that there are minors among the recruits, although the RSF leadership has repeatedly denied this.

Child soldiers are paid less than adults but can still make just under £8,000 per deployment.

It is so lucrative people spoke of families signing up all their sons, even if some were as young as 14 years old.

The RSF has fought on the frontline in Yemeni coastal towns such as Mokha.

According to former soldiers, however, they were mostly deployed to secure towns and cities captured by Yemeni troops. They also acted as bodyguards for the few Emirati soldiers on the ground.

The soldiers talked of the dangerous work, including coming under heavy fire, facing ambushes and traversing territory saturated in landmines.

No one knows how many Sudanese soldiers have been injured or killed in Yemen.

In 2017, RSF commander Colonel Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti”, suddenly announced at least 412 RSF soldiers had lost their lives.

“It’s concerning when Sudanese forces send 15,000 people to risk their lives and intervene in a deadly war that we have nothing to do with,” the RSF captain continued.

“Why are we looking to intervene in other countries when we haven’t sorted out our own problems here?” he asked.

The deal to fight the Gulf’s war in Yemen was first struck by Omar Bashir, Sudan’s long-term dictator, who was ousted by a revolution and a military coup in April.

The RSF is deployed within Yemen, while Sudan’s regular army, whose soldiers are paid less, is largely sent to the border with Saudi Arabia.

However, according to experts, payments for the RSF go straight to Hemedti, who has allegedly made a fortune from the fighting.

Since 2015 he has mostly recruited troops from Darfur, where the RSF was first established to fight Darfuri rebels who had taken up arms against the state. It is also where it is accused of carrying out Bashir’s campaign of ethnic cleansing against the region’s non-Arab population.

Once Bashir’s trusted confidante, Hemedti became part of the security apparatus that overthrew him, and so is currently deputy head of the Sovereign Council, a joint military and civilian body ruling Sudan.

Post-revolution, the new civilian and military transitional authorities are keen to bring the troops home.

Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok told The Independent that there was no military solution to Yemen – only a political one. Hemedti himself confirmed the drawdown in an interview with this paper.

But residents of Darfur say the damage has already been done.

They fear the mercenary-like use of Darfuris has militarised an already war-torn population and strengthened the RSF, which is accused by rights groups, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty, of continuing to commit alleged war crimes.

Those fears were most acute in Darfur’s displacement camps, home to hundreds of thousands of people forced to flee their villages by armed groups including the RSF.

Ismail Kharif, 23, has lived in Abu Shuk displacement camp near el-Fasher since his village Kalla was burnt to the ground in 2009 by the Janjaweed militia, a precursor to the RSF.

He said that the war in Yemen had further emboldened the militias.

“They have recruited a lot of people to join the Saudi-led alliance in Yemen, which is strengthening them by giving them money and weapons – making it unequal,” he said.

“They come back better equipped, trained and financed, ready to contribute to the massacres and killing of our people. It’s incredibly worrying,” he added.

These concerns have, however, not stopped impoverished locals trying to sign up to the RSF, even if they would naturally oppose the group.

Across town, a recently retired staff sergeant told The Independent he has been desperate to fight in Yemen so he can lift his family of 14 out of abject poverty.

Despite hating the RSF for the alleged crimes they committed against members of his own community, he is struggling to survive on a pension lump sum from the regular army of just 85,000 Sudanese pounds, roughly £1400.

“The economic situation here is dire, the only way out is to join the RSF and go to Yemen.

“Over one year you can make 3 million Sudanese pounds, so you can buy a car and a house, and retire. This is more than a lifetime’s worth of money, you can never dream of making that much,” he added.

He said since the RSF began scaling down in Yemen, it has become harder to be recruited.

“I’ve tried twice to present my papers and experience to the RSF, but they said they don’t have new spaces,” he continued.

Over one year you can make a lifetime’s worth of money, you can never dream of making that much

Sudanese soldier who has signed up to fight in Yemen

People had become so desperate to go to Yemen before Sudan completely pulls out of the war that there are reports of “RSF dealers” – middlemen who charge 100,000 Sudanese pounds, or £1400, to push applications forward.

Even with a middleman, this staff sergeant said he had little chance of being allowed to sign up as the RSF largely recruits from their natural support base – mostly Arab tribesman.

“It’s for sure fuelling divisions here,” he added, echoing Ismail in the IDP camp.

“They want to strengthen the Arab tribes, so they only really recruit from their own people.”

Mohamed* a local journalist who had been arrested by the RSF for investigating its activities, said the Yemen war has also spawned rampant corruption within Darfur and the security apparatus.

He spoke of “ghost soldiers”, where powerful families bribe officials to put down names of their sons, although they never serve.

“A friend who is a driver for the RSF boasted to me about how his name has been on the list to go to Yemen three times, but he has never left Darfur. He was still paid as if he fought,” Mohamed told The Independent.

“People with powerful connections put forward their names but never go, just their names travel to Yemen,” he added.

Another local journalist, Ahmed*, whose own brother fought in Yemen with the Sudanese army this year, said the war had even sparked clashes within the RSF.

Returning soldiers had reportedly been robbed by their colleagues shortly after taking out their massive earnings from the bank.

He said that the Yemen war has also helped morph the RSF into the most powerful body in the country.

“It’s allowed them to expand into unrelated businesses and industries, including construction and gold.”

Experts say it has been a major source of funding for Hemedti, who is believed to be a billionaire.

Profits are allegedly made by converting the Gulf’s dollar payments into Sudanese pounds using better black-market exchange rates, before paying salaries in local currency and pocketing the difference.

Hemedti himself admitted, in a televised address just days after Bashir’s ousting, that he was able to bail out the country to the tune of $1bn, partly because of the RSF’s earnings from the war.

The commander downplayed this in an interview with The Independent, saying “it was not a personal agreement”. He vehemently denied the accusations of rampant profit-making.

But Salman Baldo, from the Enough Project, which has extensively investigated the RSF, disagreed.

A warlord sitting on huge private wealth from a war in Yemen, acceding to the position of deputy head of state is very dangerous

Salman Baldo, the Enough Project

“A lot of funding comes personally to [Hemedti] from the UAE and Saudi Arabia. It doesn’t go through the central bank of Sudan, which Hemedti admits himself. It’s essentially a private military force,” said Salman Baldo.

“A warlord sitting on huge private wealth from a war in Yemen, acceding to the position of deputy head of state is very dangerous,” he added.

Jehane Henry from Human Rights Watch agreed, saying it was worrying that such a wealthy paramilitary commander remained deputy head of the Sovereign Council while the country was going through a tricky transitional phase.

“Having Hemedti remain in his position gives the impression that he is above the law. The forces he commands are allowed to do whatever they want without any real consequences,” she said.

“It is not doing enough to repair the wounds inflicted on the community in Darfur.”

* Not their real names

Read Bel Trew’s A Nation on the Edge series here:

‘Isis will be small fry’: Sudanese PM warns country will implode unless US sanctions are lifted

Women do not protest to be fetishised – their bravery should be better supported

Genocide, gold and foreign wars: Sudan’s most feared commander speaks out

Read more

Sudan’s most feared commander speaks out

As Bashir faces trial verdict, victims fear he’ll evade justice

Sudanese PM warns country will implode unless US sanctions are lifted

Inside war-ravaged Darfur where violence is killing the revolution

What Omar al-Bashir’s two-year sentence says about Sudan’s progress

Former Sudan dictator Bashir sentenced to two years ‘rehabilitation’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News