Borat v Trump: can entertainment really affect an election?

Even with the United States on red alert for pandemic containment, a pernicious phrase has been creeping into the public lexicon at an unprecedented rate of spread. We’ve been beset by a plague known as “the film we need right now”, a noxious concept used to justify and amplify the profiles of nearly a dozen releases over the past year.

Related: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm review – cinema's top troll goes baiting in Trump's US

The run-up to the presidential election has brought about an explosion of topical projects announcing themselves as a noble bulwark against the encroaching threat of another Trump term. And with them, the age-old debate over what any of this actually accomplishes has been reignited. Every time a film introduces itself as the one we need right now, it must first answer the question of whether a film is what we really need. As of late, the arguments have not been especially compelling.

A variety of approaches to critique and cinematic styles have been bound together by their shared objective of pushback against the currents of Trumpism, most prominent among them the new documentary Totally Under Control. Alex Gibney’s documentary about the current administration’s grossly incompetent coronavirus response touts itself as filmed in secret, rushed to press in time for election day with the urgency of a breaking news story. Alexandra Pelosi (yes, they’re related) and Showtime have also positioned her new documentary American Selfie: One Nation Shoots Itself in close proximity to the first Tuesday in November, its broad portraiture of a nation in crisis speaking directly to its moment. This week, Brittany Huckabee (no, they’re not related) brings a more granular analysis to the electoral process in her non-fiction film How to Fix a Primary. In each case, time appears to be of the essence.

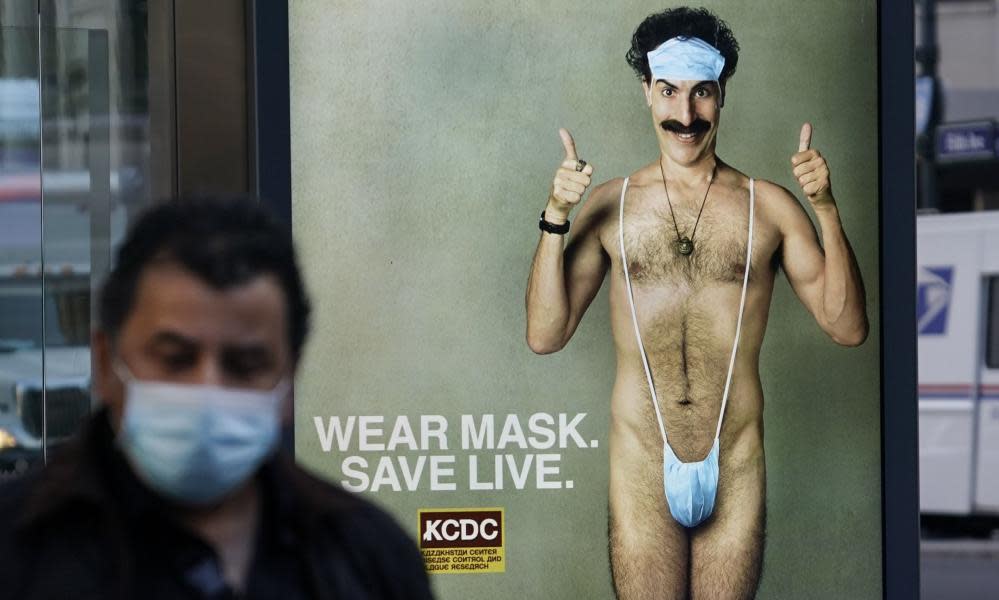

While perhaps less rigorous in terms of reportage, the Borat sequel Subsequent Moviefilm has arrived with a similar sense of gravity, with less than two weeks on the clock before the vote. And though the small-screen series The Comey Rule gave itself a bit more lead time, the Trump critiques nonetheless gesture to the coming reckoning that may or may not result in four more years of his White House. Baldest in its intentions would be the recent reunion of executive-branch drama The West Wing, the promo copy explicitly using the phrase “a call to action” to describe the program’s star-spangled defense of the democratic process. Yet there’s an air of futility to this campaign behind the campaign.

On matters like this, I often refer back to the troubling anecdote in which Donald Trump watches the 1988 Jean-Claude Van Damme vehicle Bloodsport on a plane, fast-forwarding through all dialogue so he can get to the violence and destruction. Suffice it to say that many subscribers to the Trumpist worldview are not the most receptive to the swaying powers of art. And that’s when they engage with it in the first place, the vast majority being unlikely to give the time of day to an entertainment so openly trumpeting its liberal bona fides. Those films that make an active effort to reach across the aisle and appeal to a theoretical rightwing viewership often undermine the point they’re making. The Comey Rule often strains to paint Republican higher-ups as helpless objectors against Trump’s bulldozing influence, where complicity didn’t have to be dragged out of anyone. For this seeming reluctance to alienate the unconverted, it’s a weaker work.

In this light, many of the aforementioned productions start to look like acts of self-congratulation in the guise of activism. This flattery of an agreeable faction was the cardinal sin of the ardently anti-Trump Coastal Elites. To mix religious metaphors, it delivered a full-throated sermon to the choir it characterized as more enlightened than the poor saps in Trumpland. Even something as steeped in journalistic motivations as Totally Under Control runs through the talking points half of America already knows by heart, leaning on the holistic awfulness of Trump as a conclusion unto itself. This tendency clarifies itself on the opposite end of the political spectrum; everyone’s favorite propagandist wingnut Dinesh D’Souza has readied another one of what could be charitably termed his “movies” in time for November, the conspiracy-mongering screed Trump Card. The D’Souzian approach favors directness in how it affirms all the beliefs of its simpatico partisans, but his ideological opposites indulge in saner versions of the same tactics.

The most successful films tackling the horrors of this hellacious year have come at it from an angle, remembering all the while to be a movie before a message. Ai Weiwei’s pandemic documentary Coronation made its case through elegant juxtapositions of editing, letting his points organically arise from the footage instead of through voiceover narration. In the case of Borat, it helps that Sacha Baron Cohen is still hysterically funny after all these years. The film only falters near the end, as a final title card belittles everything that’s come before by framing the whole thing as an exhortation to get to the polls. The undecided voter who’s remained steadfastly on the fence for the past year, waiting until Borat’s endorsement to form an opinion two weeks out from the big day in November, must surely be a myth. As the oft-misattributed saying goes, if you want to send a message, try Western Union. If you truly want to sway voters, sign up to phone-bank.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News