Bradley Cooper Tells Us Acting Wasn’t the Secret of His ‘Maestro’ Success: ‘I Would Believe That I’m Him’

“Maestro” makeup artist Kazu Hiro misses Bradley Cooper’s Lenny. “This is the first show I felt like, ‘Oh, at the end of the filming, we can keep going. He was so fun.'”

For them, every shooting day began with hours in the chair as the two-time Oscar-winning makeup artist Hiro (“Darkest Hour,” “Bombshell”) silently applied Cooper’s makeup that would allow him to portray 40 years of the composer-conductor’s colorful life.

More from IndieWire

“We don’t talk much,” said Hiro, who was part of a “Maestro” panel that I hosted for Netflix’s Tudum event January 13. “It’s a long day, so it’s quite tough. And he asked me to do the makeup by myself. Usually we make a team, but he noticed that everybody has a different brain and eyes and hands. He needed space. That helped Bradley to focus and get ready for the film.”

Even on a normal day, Cooper is up early: Feed the dogs at 5:30 a.m., do a “life changing” cold plunge for three minutes, wake his daughter, make her breakfast, walk her to school. While shooting “Maestro” in New York, his mother took over his routine and Cooper discovered a new one.

“No one’s around base camp,” he told me on Zoom. “There’s like one person there, maybe two, and it’s all dark. It’s still night and you walk in a little trailer. And there’s Kazu waiting. Yeah, it was wonderful. It felt very calm and tranquil. I did enjoy that.”

The makeup time extended to five hours “in the older stages,” said Cooper, “because there was a body, and then arms and hands. One scene when he’s dancing it’s a full-body upper torso prosthetic.”

When Cooper left the makeup chair, he was Leonard Bernstein and he stayed that way. It was just easier, he said. “The crew was like, ‘Oh, we got a young Lenny today. This is going to go faster.’ Older Lenny was a little more bruising.”

Production sound mixer Steve Morrow, another panel member, described it as making the movie “without Bradley. It was kind of weird. But at the end of the movie, when he’s not in makeup, it was like, ‘Whoa, who are you?'”

“But it also wasn’t weird,” said Carey Mulligan, who spent years preparing to play Bernstein’s wife Felicia Montealegre and landed her third Best Actress nomination for her work in the film. “I don’t know how else you could have done it, really.”

Said Cooper, “We did everything we could to create an environment that people felt at ease, and that they don’t have to act, and you just explore. And the best way for me, also to save time, was just to be ready all day. And I really owe that to the crew that didn’t just laugh at me all day long.”

Far from it. Their efforts earned “Maestro” seven Oscar nominations: Picture, Actor, Actress, Original Screenplay, Cinematography, Makeup & Hairstyling, and Sound.

Mulligan said that as a director, Cooper’s own vulnerability set the tone. “An actor’s biggest fear going into something is that people will judge you or that you will somehow make a fool of yourself,” she said. “And if the person who’s directing the film is also taking the biggest swing, from the minute you get to set. … Every other actor that comes in feels like they can play around wherever you want. There’s no judgment and that’s just the biggest gift. I just loved it.”

The crew was the same, said Morrow: “I think we all strived to be as as invested in Bradley.”

Everyone — including Cooper — got used to the director as Lenny. “The leap of faith happens in the trailer before crew call,” he said. “I didn’t have a separate trailer for getting changed. We just have a curtain bisecting the makeup trailer and then Lenny’s wardrobe for that day would be there. I would put that on and then I would always make that leap of faith before I would come back for the finishing touches, to put on the wig or the eyebrows. I would fully go into the voice of Lenny and believe that I’m him.

“I hoped that he would come every day into me,” he said. “It was scary, the idea of it not happening and I would have to act. But thank goodness every day of the 55- or 56-day shoot, it did happen. So then I’m just me as him and then directing and acting in the movie. The crew were so kind to embrace that illusion. I never felt vulnerable in a way that would shut me down. Instead, it felt like everybody was living in this illusion that Lenny was there.”

In one moving scene between Bernstein and his daughter Jamie (Maya Hawke), the father lies to her about rumors that he is having homosexual affairs. “I wasn’t compartmentalizing in my brain,” said Cooper. “Lenny isn’t a liar, and certainly not to his children. And it would be hard for him to reason with himself why he wouldn’t tell Jamie at this time of her life the reality of his relationship, their parents, how he lives his life, what it is to be human. There was a moment where I felt compelled to tell her the truth, which wasn’t in the script that we had written. And I almost did, but in my brain I started to think about the ramifications script-wise and shooting-wise and how we would have to write another fight. That would impede upon the whole structure leading to the huge Thanksgiving fight. That all happened in the in the span of maybe five seconds on film, and then I decided, ‘It’s not worth it.'”

Watch the scene in the movie and you can see it on his face. “I don’t know how much of that is me,” said Cooper. “Again, it’s that leap of faith where I just trusted it was him. There’s the side of me that was processing it as me but he was also processing as him because he wants to tell her, so story-wise, it worked. I could just be there.”

Writing the script with Josh Singer helped. “I would have a harder time directing something that I hadn’t co-written,” he said.

Singer developed the script for a decade with Martin Scorsese, and then Steven Spielberg, before Spielberg passed the baton to Cooper 10 minutes into watching “A Star Is Born.” Cooper met Oscar-winner Singer (“Spotlight”) at that same screening and “liked his energy,” he said. “We were both from Philadelphia. I could tell his love for the project. And if he was open to starting a new journey with me. I would be a fool not to walk down that path with him.”

Cooper zeroed in on the marital drama at the center of Bernstein’s life. “I’m always thinking about the audience,” he said. “‘What story do I want to watch, and can learn from?’ Their relationship can teach us so many things about just being human. There was so much hypocrisy, complications, beauty, joy. And that could function as a wonderful way to incorporate his achievement musically, because the melody with which they spoke, it just started to feel like music to me.”

For the soundtrack, Cooper did not pick the best-known or most accessible Bernstein pieces. For every piece of music that he chose, he asked the question, “What’s the story and what music serves the story?”

“The idea of the clarinet, for example, being identified with David Oppenheim [Matt Bomer], who was a clarinetist, this other element of his life. The musical theater aspect, ‘On the Town’ felt like the perfect way to represent that contribution. Mahler felt like the perfect example of watching how he was able to stand in the center of the sun and not be burned alive, but instead diffuse the light to all of us.”

Cooper started working on Bernstein’s voice with dialogue coach Tim Monich back in 2017. In one early recording, “he has this wonderful, melodic, high-pitched voice. And then there’s all of the Norton lectures where you’re hearing him much more raspy. He had a deviated septum, and he became emphysemic when he was older because he had asthma since he was a kid. I observed how dramatically his voice changed as he grew older.”

Bernstein’s earlier time periods are shot in a classic 1.33:1 aspect ratio, in black-and-white. “[We never wanted] the audience to feel like they had to work to go into that time period, or that they were being told that these actors are pretending it’s 1945 or 1955,” Cooper said. “Our incredible crew created an environment that we feel is a living breathing time period. Yeah, if I saw it in color, I would have to do some sort of gymnastics in my brain to then believe it’s real.”

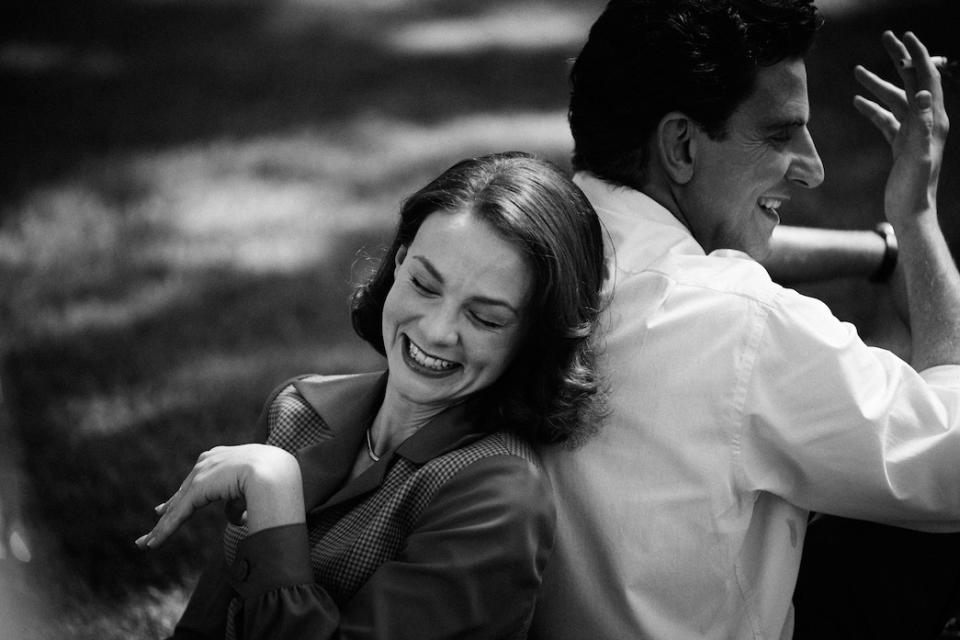

Some of Cooper and Mulligan’s early improvisations and game-playing wound up in the movie; the numbers guessing game came from their work in dream workshops. “We were doing an exploration during preparation and we found ourselves being back to back,” said Cooper. “It was just a beautiful feeling of both of our weight on each other, and one person giving over one point and the other person holding the other person up. We thought, ‘This is a wonderful visual motif for the film.'”

The last section of the movie is devoted to Felicia’s illness. “I just wanted the audience to fall in love with her,” he said. “I’ve been in love with people who I’ve had to watch suffer. We were trying to create a story where you’re sitting with them and their sickness and it’s just absolutely devastating. That was also a part of the toll of her choices. That’s why there’s smoking everywhere. She’s always playing with a lighter.”

The “Maestro” piece de resistance is a six-minute sequence of Bernstein conducting the London Symphony Orchestra playing Gustav Mahler’s Symphony Number 2 at Ely Cathedral in Cambridge, England. Cooper tried five or six set-ups on the first day, but was dissatisfied with the results. On the second day, he deployed an uninterrupted shot on a techno-crane.

“I stopped worrying about getting it wrong and allowed myself to really communicate with the orchestra,” said Cooper. “That’s all I was trying to do was receive and provoke this Mahler composition from them through me, and for us to celebrate in that Cathedral. That take, I completely gave over to that fearlessly. Of course, there are tons of mistakes but that communication between conductor and orchestra was occurring. On the previous day, I would forget where I was, I was self-conscious, all of those things, and I just was acting it.”

The timpanist went up to Cooper afterward and said, “Yesterday, you didn’t get it at all. Today, you just conducted us.”

Cooper felt pressure on that scene, he said. “The pressure was, if I don’t serve Lenny and his gift in this scene, the whole movie doesn’t work. The movie had to somehow replicate the magic which he was able to wield and then impart on others.”

“Maestro” is now streaming on Netflix.

Best of IndieWire

2023 Emmy Predictions: Who Will Win at the Primetime Emmy Awards?

2023 Emmy Predictions: Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Special

2023 Emmy Predictions: Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Series

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News