Bridget Fonda at 60: the Nineties great who vanished without a trace

Before she retired in 2002, the actor Bridget Fonda had perfected the art of inscrutable decision-making. She picked projects as if she were in a pinball machine: a romcom here, a psycho-thriller there. “Do you want to star in a colonic irrigation comedy with Sir Anthony Hopkins?” she was (more or less) asked in the early Nineties. She’d say yes, then find herself on the set of a forgotten debacle called The Road to Wellville. It was just another inscrutable detour in a career defined by its indefinability.

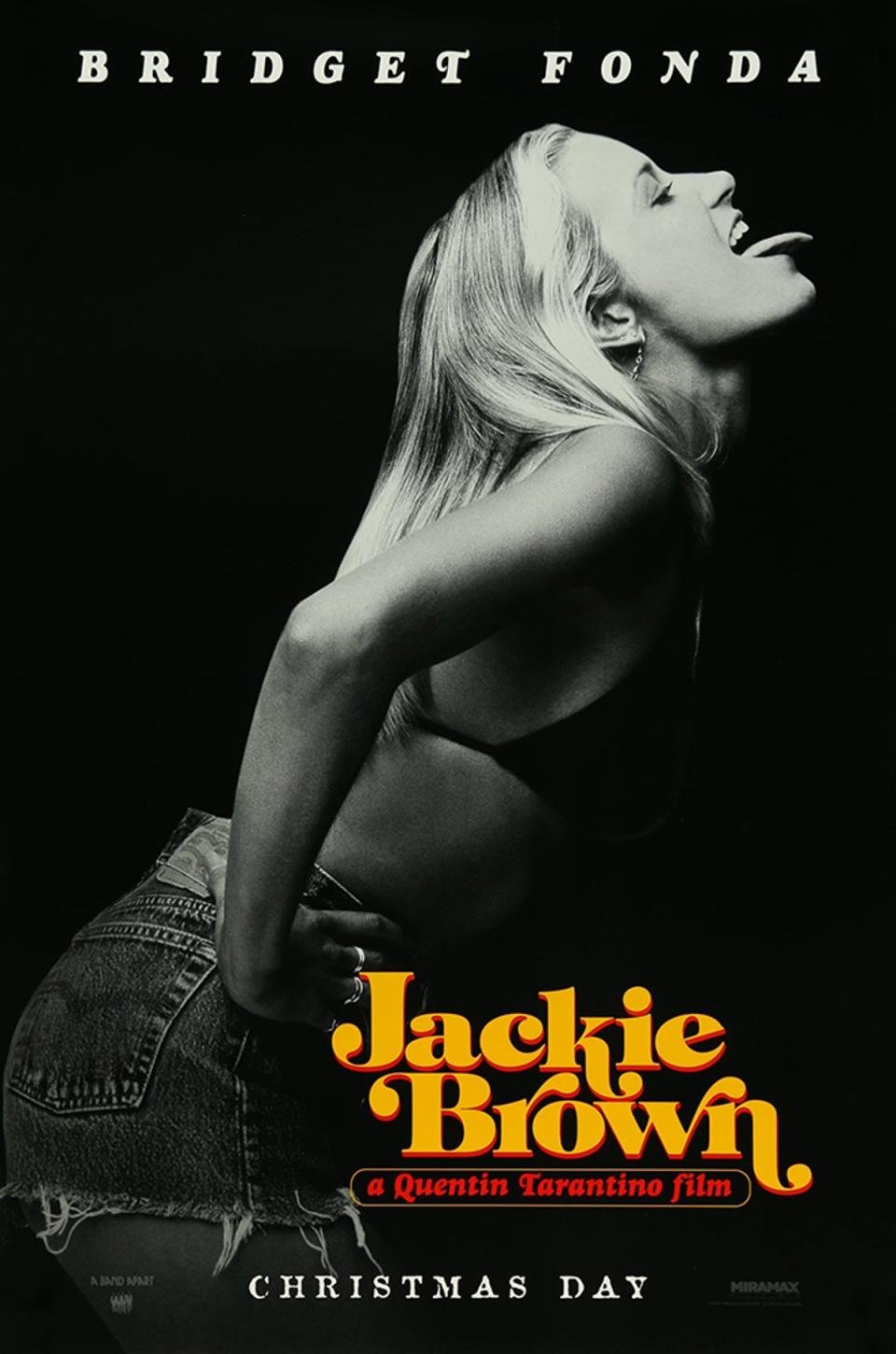

Fonda – the granddaughter of Henry, daughter of Peter and niece of Jane – turns 60 on Saturday. It’s been 22 years since she last acted. But many of her movies hold up, markers of a time in filmmaking that valued sex and romance, ideas and provocation. She was a ribald Mandy Rice-Davies in the Profumo affair movie Scandal (1989), and a Minnesotan Lady Macbeth in Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan (1998). In Cameron Crowe’s Seattle grunge tapestry Singles (1992), she dreamt of love, body modification and rock stars. She had such an enviable haircut in the lurid B-movie Single White Female (1992) that her loopy new roommate Jennifer Jason Leigh swiped it, then her boyfriend, and then everything else. In 1997’s Jackie Brown, Quentin Tarantino cast her as a scheming, perma-stoned surfer girl, all bikinis and toe rings.

Fonda appeared in almost too many films for someone only in the public eye for 15 or so years. Some are well remembered (that’s her as Andy Garcia’s photojournalist fling in 1990’s The Godfather Part III, for instance). Others are cult curios: that farcical crocodile movie Lake Placid (1999); Point of No Return (1993), the ill-fated US remake of La Femme Nikita; Henry Sellick’s doomed animated/live-action hybrid Monkeybone (2001). A few only sound made-up. Rough Magic? A supernatural romcom from 1995 in which Russell Crowe tails her to New Mexico before she’s given mystical powers by a legendary shaman? Surely not! What I’m saying is that Fonda had an intriguing, quietly brilliant acting career for a while. Then, in the blink of an eye, it stopped.

Here’s what we know. In 2002, Fonda starred in a made-for-TV film adaptation of The Snow Queen. In early 2003, she signed up for a recurring role on the legal drama series The Practice. Weeks before filming was due to begin, she was driving down the Pacific Coast Highway when her car lost control, flipped over an embankment and tumbled downhill. She emerged – “miraculously”, according to a Page Six article from the time – with mere cuts and bruises. Her role was recast in The Practice, then a few months later married her boyfriend, composer Danny Elfman, had a baby in 2005, and made her last official public appearance in 2009, at the premiere of Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds. That’s, believe it or not, the entirety of it. Pestered by a paparazzo at a Los Angeles airport last year and asked if she’d ever return to acting, Fonda replied politely yet firmly: “I don’t think so – it’s too nice being a civilian.”

Fonda didn’t retire like Gwyneth Paltrow retired. She didn’t shift her public profile to a different part of popular culture, as in moving from movies to vagina candles. Fonda just upped and left. There were no airs and graces, no statement to the press. Her last major movie was 2001’s stylish Jet Li actioner Kiss of the Dragon, and it made bank at the box office. There wasn’t a slow, depressing professional decline. So it’s no surprise that a Reddit thread pops up every once in a while fielding theories on why she vanished, as if “the disappearance of Bridget Fonda” is one plot twist away from becoming a Netflix true crime series.

I, admittedly, used to be one of those armchair detectives, ginned up for the most part on Nineties nostalgia. I remember discovering her as a child of five or six, left dazzled by her on the poster for Jackie Brown. Fonda occupied an unusual amount of my mind after that. She always seemed to be in the pages of Empire or Neon, film magazines I’d cut up for scrapbooking after my dad had read them, as well as newspaper ads for her many, many movies. Then she went away, and only years later did I begin to actually explore her filmography. Her CV, it turned out, was a glorious mish-mash of things. She changed hair colours and accents, played glamorous sophisticates and reckless naifs. She was a superlative movie star. I had to know why she stopped.

When I see people from a non-entertainment-industry family who’ve made it, I’m like, ‘Wow, you’re here because of your own efforts.’ I can’t allow myself that, because I always factor in nepotism

Bridget Fonda in 2000

Dig into the Fonda archives, though, and her early retirement isn’t quite the mystery it’s made out to be. Throughout her career she would speak uncomfortably of herself, as if her job was an itchy jumper she threw on without thinking. “What is it with my low self-esteem?” she once asked herself during an interview. “I’m trying to be happy with my career. I think I should give myself a break, but I’ve got this bug that rides me. ‘You should be doing better.’ Every time I work, I’m frustrated with my physical inability to catch up to my mental picture.”

When she was promoting the 1994 road movie Camilla – think Thelma & Louise with less cliff-edge and more of Jessica Tandy skinny-dipping – she seemed to use its press tour to get to grips with herself. “I play a musician with terrible stage fright who has these big, hungry dreams,” she said. “She’s got talent, but she is so acutely aware of those who are geniuses that she feels small and not good enough. It’s my life.”

Fonda does, of course, come from phenomenal stock, so it’s not hard to imagine her feeling dwarfed by comparisons. Potentially to her detriment, there was never any proto-nepo baby defensiveness when her famous relatives were brought up in interviews, either. “When I see people from a non-entertainment-industry family who’ve made it, I’m like, ‘Wow, you’re here because of your own efforts,’” she told The Guardian in 2000. “I can’t allow myself that, because I always factor in nepotism.”

Quotes like that make Fonda seem remarkably level-headed, but you almost wish she had a little more delusion back then. Regardless of whether she got a leg-up in Hollywood because of her name, her performances made her one of the best American actors of the Nineties – and, with that decade more than 20 years in the rearview, increasingly one of its most unsung.

Fonda could be daffy, dark, urbane and downbeat, and had a smile that could read as both radiant or aloof. She excelled at uncertainty and aimlessness, at women struggling to find their way in the world. Two of her best early performances hinge on shock moments of clarity: in Bodies, Rest & Motion, a 1993 drama she made with Tim Roth, her then-boyfriend Eric Stoltz and the similarly retired-early Phoebe Cates, her character is told by a man that he’s all she can hope for. She snaps back, newly enlightened: “You’re ‘the one’? I’m 20-f******-8 years old, I’ve had lots of ‘ones’ – you’re just the latest.”

That sense of creeping resolve underpins the best of Singles, too, a film that only ever touches greatness when she’s on screen. Its peak is when her character, a meandering waitress, finally decides to put herself above the demands of the men in her life. We see her dance in her kitchen, read literature, then sunbathe on her rooftop while listening to The Replacements. “Being alone…,” she says in a voiceover, “there’s a certain dignity to it.”

As Fonda moved through the Nineties, her work became more textured and complex. Tarantino once said he cast Fonda in Jackie Brown because he thought she had “a performance in her that she hadn’t given – I wanted to be able to bring out that wild, cunning side that I felt was bubbling underneath her work”. It’s why her sluggish, slippery Melanie is so thrilling to watch. It’s as if she’s taken the anxious discomfort of her earlier work (“What if your ambition is to get high and watch TV?” Melanie asks at one point), before adding shades of sociopathy. A Simple Plan, released a year later, went one further. We meet her barefoot and pregnant, an ancillary supporting player to three men who stumble upon – then steal – $4m. As the film unfolds, though, she becomes its most ruthless character, someone sly and manipulative and completely naked in their greed.

Fonda had been great for years by the tail end of the Nineties, but both Jackie Brown and A Simple Plan seemed to propel her to new creative heights. Today I wish they were the beginning of something, rather than her final bow. That said, Fonda was never an actor who followed a traditional trajectory. Her picker was always pleasingly erratic, a random assortment of crowd-pleasers and arty gambles. She worked with some of our most revered directors, but often in their most underseen movies: Noah Baumbach (in 1997’s Mr. Jealousy), Paul Schrader (in Touch, also from 1997) and Bernardo Bertolucci (in 1993’s Little Buddha). She once called self-promotion “sort of shameful”. Is it any wonder she’d go even further into idiosyncrasy by leaving the business altogether?

In one of her last splashy profile interviews, for Mirabella to promote Jackie Brown, she recounted an experience that seems to get to the crux of her and everything that happened over the subsequent few years: the stopping, the vanishing, the “civilian life”. It was early 1997, she recalled, and she was bedridden with flu. She slipped into what she described as an “outrageous depression”, and found herself becoming increasingly emotional, crying over the brightness of the light outside her home and unable to explain it. She asked her mother for help.

“She said, ‘Oh god, Bridget, you get that from me – it’s that thing that happens to you at a certain time in life, when you realise that life isn’t going to happen to you. It’s not for you to discover. You actually have to make your life’.”

And when you think about it, and whether we like it or not, she sort of did.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News