Brief Encounter, Cunard Queen Anne: Cruise-line entertainment has never been this classy

Noël Coward spent a good deal of time travelling by sea, often scribbling as he sailed. He wrote much of the operetta Bitter Sweet (1929) on ocean liners, and set his 1961 musical comedy – Sail Away – on one. Indeed, he first clapped smitten eyes on New York in 1921 after travelling on the beautiful Cunard liner, the Aquitania – which set sail from Southampton.

So it’s fitting that Emma Rice’s adaptation of the classic Coward weepie Brief Encounter – first staged in 2008 in a converted cinema on the Haymarket – should be part of the upper echelon entertainment ‘offer’ on the latest Cunard cruise ship, the Queen Anne.

This behemoth embarks from Southampton on its maiden voyage on Friday, bound for Portugal initially, but with the world its oyster. That’s a romance-stirring prospect in itself. The vessel is a beguiling throwback to the gilded age in which Coward was going full steam ahead – with its art deco stylings, and spick-and-span crew oozing a politeness barely heard since the pre-war years.

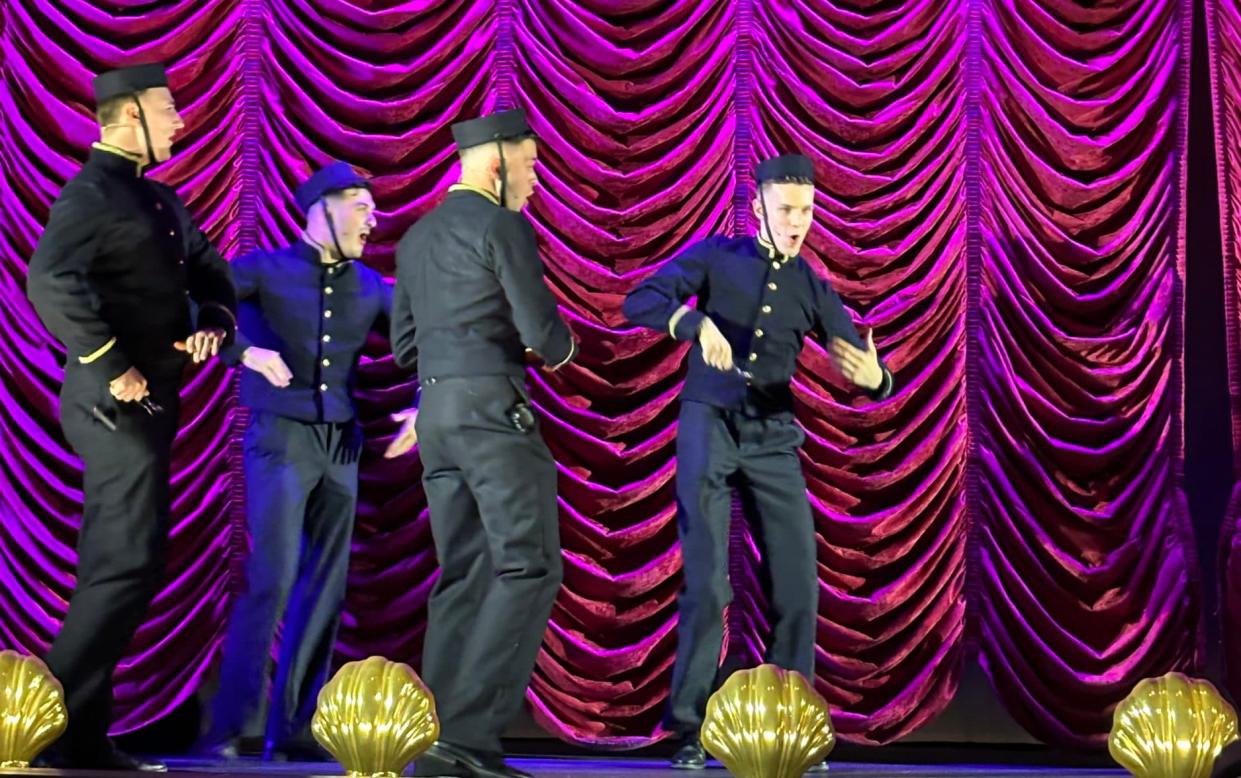

On Wednesday night, Rice’s charmer of a show – snipped to a manageable but not meagre-feeling 65 minutes, and redirected by Simon Harvey – inaugurated the Queen Anne’s plush ‘Royal Court’ theatre, which seats twice the number (800+) as its Sloane Square namesake.

The venture follows in the wake of a few other artistic voyagers (the RSC made its Joan Littlewood musical sea-worthy), but producer David Pugh is really pushing the boat out here. His youthful company of 11 will also take on board another of his hits, Pride and Prejudice (*Sort Of). They’ve signed up for six months, like some nautical equivalent of weekly rep.

Requirements include being in possession of sea-legs, the ability to cope with adverse weather’s impact on the set and the fact that audience-members may drift in and out mid-performance, as they’re free to do.

Losing interest isn’t much on the cards, though. The piece, drawn from the 1936 one-act play Still Life, the resulting screenplay for David Lean and sundry Coward songs and poems, initially brims with comic energy then swells with high emotion. It rolls between theatrical and cinematic elements as it imparts the tempestuous, adulterous affair of Laura Jesson and Alec Harvey, climactically denoted by crashing waves in a homage to the film.

Is Rethea Coles – making her acting debut at 20 (the same age that Celia Johnson, who starred in the 1945 film adaptation, first trod the boards) – too young to convince as the married suburban mother of two who’s amorously stirred when the kindly doctor dabs grit from her eye at Milford Junction caff? Strangely, not – the period-faithful accent gives her an old-fashioned air, and there’s something sweetly girlish, too, about those restrained kisses with Scott Royle’s dashing Alec. The acting is first-class across the boards, and the production values a close match for the West End. A choral arrangement of that Rachmaninoff piano concerto contributes to the winking, all-hands-on-deck ensemble ethos, while technical ingenuity has the protagonists step magically into the silver screen. I’m sure the Master would have approved.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News