Bring it all back: why naff noughties pop is suddenly cool again

The turn of the millennium is not generally considered a vintage era for mainstream music in the UK. Sandwiched between Britpop and the mid-00s indie revival, it was a period dominated by talent show winners, girl- and boybands, ex-boyband and girlband members, acts with tie-ins to kids’ TV shows, and doleful singer-songwriters such as Dido and David Gray. It was sometimes trite, occasionally rapturous and – Dido and Gray aside – frivolous, family-friendly fun.

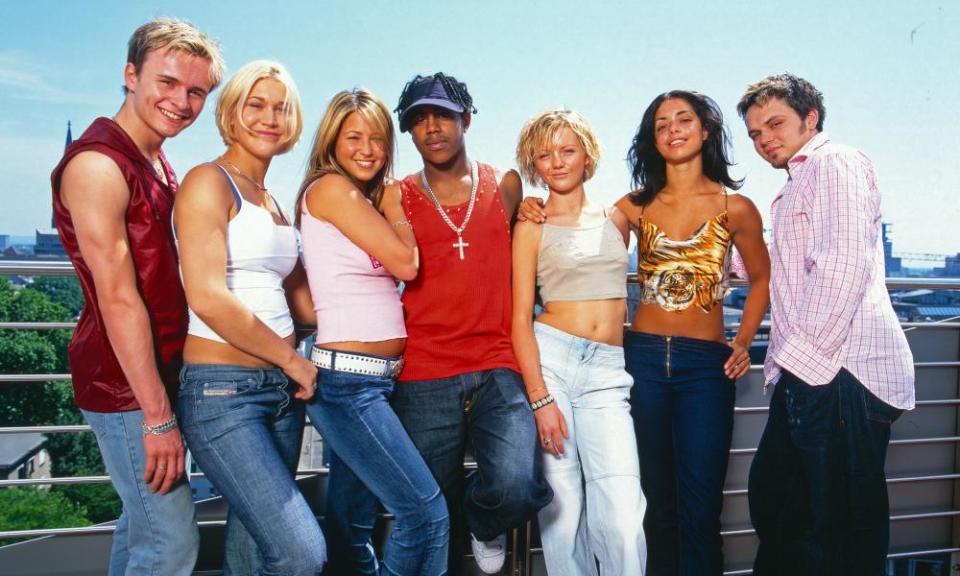

It isn’t, in other words, an era you’d expect a pop star on the cultural vanguard to be into. Yet last month Lorde revealed that her forthcoming third album was influenced by what she calls “early 00s bubblegum pop” – in particular, tween-targeted hitmakers S Club 7, Natasha Bedingfield, Natalie Imbruglia, All Saints and Nelly Furtado. She is not alone – the reclamation of late 90s and early 00s mainstream pop by young artists is now fully under way. Many heard shades of S Club in Dua Lipa’s 2020 album Future Nostalgia, and Lipa’s single Don’t Start Now had more than a bit of Spiller and Sophie Ellis Bextor’s 2000 smash Groovejet in its DNA.

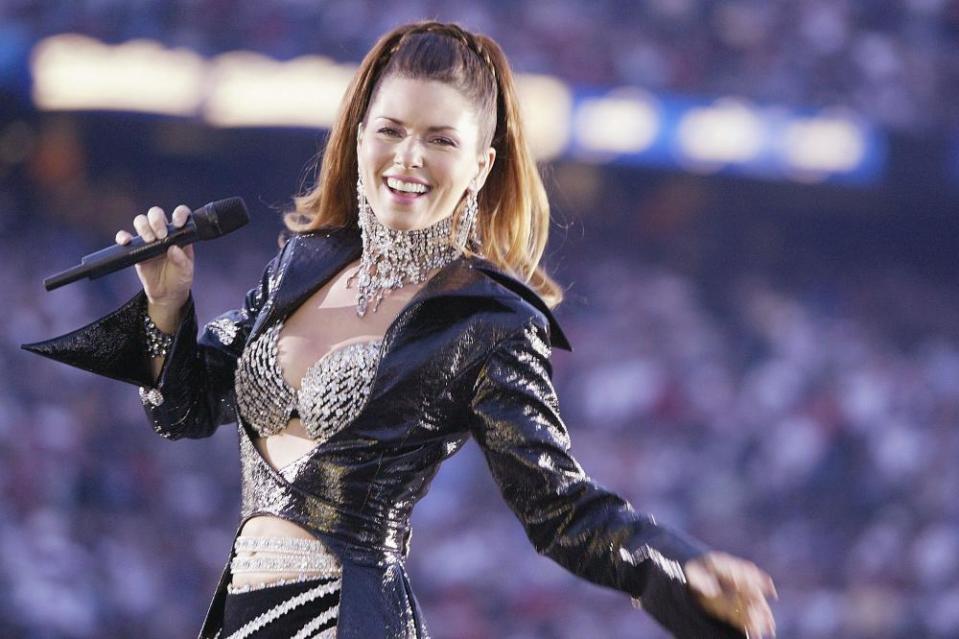

Rina Sawayama, whose debut drew on an array of 00s-era sounds, has cited the “00s Britpop” of Girls Aloud as a key influence on her forthcoming second album. Now I’m in It, from Haim’s last album, was widely compared to Savage Garden. Last year AG Cook, founder of the avant garde pop label PC Music, released Oh Yeah, a deeply turn-of-the-millennium single inspired by the work of Shania Twain, whose influence was also detected in Caroline Polachek’s debut solo album; the former Chairlift frontwoman later covered the Corrs’ 2000 smash Breathless. Last summer, a cover of Dancing in the Moonlight, a 70s hit that Toploader took to No 7 in 2000, peaked at No 11 and spent 20 weeks on the chart.

Online, nostalgia for this era is off the charts. S Club 7 and B*Witched are the subject of much reminiscence on social media (the latter also feature heavily in Maya Erskine and Anna Konkle’s brilliant Y2K-set comedy Pen15), as is Vanessa Carlton’s 2001 hit A Thousand Miles (a particularly beloved sample of young rappers, including Rico Nasty and Yungeen Ace). Natasha Bedingfield’s 2004 single Unwritten has enjoyed a prominent afterlife on Twitter and TikTok, where it has spawned two challenges and soundtracked more than 100,000 videos.

These influences cover a broad sonic range: Twain’s country-pop is not the same as S Club 7’s retro bubblegum pop or Imbruglia’s post-Alanis pop-rock or Bedingfield and Furtado’s looser, R&B-informed pop. What ties them together is a tendency towards hyper-accessible melodies, clean production and commerciality. This was music free of edge, raunch or lyrical complexity, often masterminded by labels, and not taken seriously at the time. It hasn’t attracted much critical scholarship since. Is it time for a re-evaluation?

If fashion is anything to go by, this musical revival is slightly overdue. After the early 90s fashion revival that began a decade ago went stale, the zeitgeist moved on like clockwork, and Gen Z resurrected double denim, small bags, low-rise jeans and butterfly clips. Nowadays, fashion operates reliably by the 20-year rule, whereby the aesthetic most deeply fossilised into uncoolness, ugliness and awkwardness begins to seem fresh, subversive and exciting simply because it has been out of favour for so long. It’s not much of a stretch to apply that mentality to music: as critic Carl Wilson wrote in Let’s Talk About Love, his reappraisal of Celine Dion, there can be a point at which epochs once considered “abject” start to “sound charmingly strange”.

Yet nostalgia for this era may be more than just the result of mechanically revolving trends. There’s a sense of it as a prelapsarian time. Slayyyter is a 24-year-old LA-based musician making waves with her strain of hyperpop, which harks back to sugary Y2K chart fodder. She describes the revival as an “escapist movement”, a rejection of the seriousness and scariness of the present day; an imagined return to a simpler age. “I feel like everyone’s brain was turned off,” she says. “It was vapid in such a fun, cool way. Now everyone’s so overstimulated with all this information, the world is in flames, the environment is heading towards absolute destruction – everyone’s longing for the days of pop music when there wasn’t so much doom in the air.”

It is, she says, a way of resurrecting a carefree childhood, which is also something Charli XCX and Troye Sivan articulated in their collaborative single 1999, a rose-tinted paean to the era of “no-phone” socialising and early Britney that yearned for the salad days of youth from a 20-year remove.

Pre-social media, pre-heightened awareness of the climate disaster and, of course, pre-pandemic, it’s not difficult to see why the period holds such appeal to artists barely old enough to remember it. In hindsight, it seems like a safer era (for privileged westerners, at least), before the threat of terrorism sparked by 9/11 calcified into a routine anxiety; and a more economically optimistic one, before the financial crash that began in 2007. That it was soundtracked in part by such cheerful and catchy tunes reinforces the idea that it was a better, less unsettling time. Jordan Paramor, one-time Smash Hits writer and author of books on Steps and S Club 7, describes those late 90s and early 00s pop acts as “selling happiness”, while Lorde has said she heard “optimism” in this period of pop.

For some artists, the CD:UK years offer an escape from the homogenisation of contemporary music that Slayyyter says “has had the soul sucked out of it. I’ll hear a hit song from now and be like, I feel like I’ve heard this song a thousand times before.”

Despite this era’s preoccupation with slick, glossy pop, much of what is returning now involves “real” instruments – especially what the critic Jessica Hopper has referred to as “toxically cute 90s pop guitar”. Heather Baron-Gracie, frontwoman of Manchester indie-pop group Pale Waves, suggests that this era offers respite from the way much music is created nowadays. “I love pop music but I can’t for hours listen to the same beat made in Logic or the same synths that everyone’s using from a certain synth programme,” she says. “You listen to the radio and it feels like the same song. I love real music with real instruments.”

Like Lorde, Baron-Gracie drew on the “90s acoustic feel” of Natalie Imbruglia’s sound for Pale Waves’ second album (the band also recently covered her 1997 hit Torn). And while her initial material drew from Britney-esque pop, Slayyyter found herself increasingly drawn to live instrumentation on her debut album Troubled Paradise, finding inspiration in the early 00s “era of pop-rock girls” such as Ashlee Simpson, Lindsay Lohan and Michelle Branch. Meanwhile, on her clean, crisp recent single Your Power, Billie Eilish recalls the limpid earnestness of David Gray and Dido.

Some artists have revelled in unpicking the seams of these immaculately packaged childhood artefacts. PC Music founder AG Cook brought acoustic guitar-driven pop-rock into his previously hyper-digital sound, using Shania Twain’s work as a reference point. “It has a lot of personality, and is also really airtight and slick,” he told me last year. “It’s so overproduced in the way that I like but she’s a country singer vocalist, so you have this strange interaction.” (Incidentally, paintings of Twain and her horse featured in the latest show by artist Sam McKinniss, who painted the cover of Lorde’s second album, 2017’s Melodrama.)

Considering the interplay of artifice and authenticity in the work of Twain – or, indeed, any of these acts – is a postmodern enterprise: it was scarcely considered meaningful back then, neither by critics nor the labels behind it. Unlike the Timbaland-aided innovation taking place in mainstream R&B in the US at the time, this strain of pop was widely considered a throwaway art form: CD sales made it a short-term profitable enterprise for labels, who were “pumping out loads of new acts” in order to make as much money as possible, explains Paramor.

It was also designed to be heard in a superficial way, she says. “Deep down, people knew some of it was a bit crap but didn’t really care, we enjoyed it at face value.” There was an assumption that manufactured bands did not write their own material, meaning their work seemed more like a consumer product designed to provide pleasure than a meaningful form of self-expression. For many, this two-dimensional quality was a reason to scorn the whole thing. Colin Kennedy, who was commissioning editor at Smash Hits in the late 90s, remembers pop being “mostly dismissed as a phase teens needed to pass through before they discovered real music”.

Natasha Bedingfield, the singer-songwriter whose jubilant early 00s pop is celebrated daily on social media, was no industry puppet. Her label was extremely involved though, attempting to model her on its previous success Dido, and banning her from wearing hats. And she recalls “some stigma around” the idea of pop at the time. “I remember always explaining myself – ‘It’s pop music because it’s popular, it’s anthemic.’ Reframing the word ‘pop’ a bit.”

She puts today’s revival down to people needing something “positive”, and her presence in childhood memories of young artists: she recalls Lorde telling her how her sister sang Unwritten at her graduation. (The influence has come full circle: Bedingfield’s new single, Lighthearted, is an exercise in cool, sparse Lorde-like pop, and the video features the dancers who made Unwritten trend on TikTok.) She also attributes it to a belated acknowledgment of the skill that goes into making good pop: creating clever rhymes and ensuring a song is “for everybody”, she says, is a fine art (one she sometimes collaborated on with Danielle Brisebois of the New Radicals, another vestige of this era). “It’s like tabloids. It takes a lot of skill to put all of those puns together. Those are the things that get in your brain.” Over the past 20 years, she says, “my own respect for the craft of pop has really grown”.

Bedingfield is not the only one who has changed her tune. The recognition of pop music artistry is now expected. Granular, chin-stroking critical discussion is the norm, thanks to poptimism, the mid-00s backlash against rockism – the prevailing prejudice that the only meaningful and serious music was created by men with guitars. But poptimism came slightly too late for the obvious, unashamedly commercial pop that arrived in a cluster around the turn of the millennium. A new generation that never internalised those old assumptions may be rectifying that.

“That whole chorus-verse-chorus song structure that was designed to punch through radio blandness has turned out to have the catchy immediacy that TikTok thrives on,” says Kennedy. “Personally, I am not surprised that today’s generation – released from all music snobbery and tribalism – have scoured Spotify and found the ideal soundtrack for their TikToks and IGTV clips in the bright, breezy and disposable pop of 20-plus years ago.”

Perhaps, too, the embrace of this music is a rejection of poptimism’s seriousness and respectability: a response to the po-faced chic of much contemporary pop, says Slayyyter. “Everyone’s trying so hard to be the coolest person in the room that a lot of magic in pop music is lost.” However many dimensions are at play here – nostalgia, rediscovery, post-irony, genuine enjoyment – one thing is clear: for the current generation of history-raiding musicians, absolutely nothing is off limits.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News