Bristol celebrates its poet genius who died at just 17

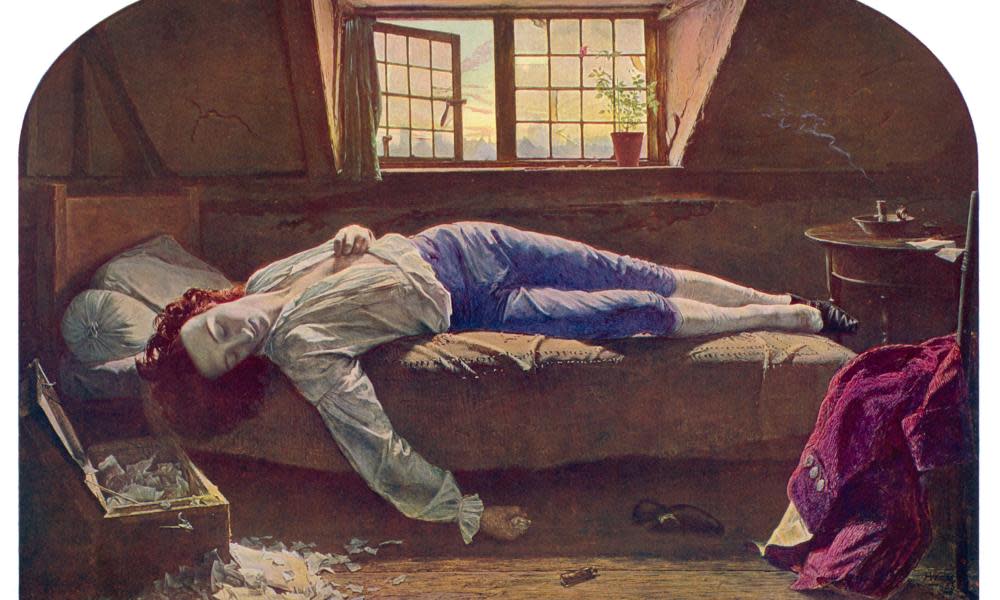

He was revered by poets such as Wordsworth, Shelley and Coleridge and a romanticised painting depicting his deathbed remains an enduring image of doomed artistic talent.

Now a series of projects marking the 250th anniversary of the death, at the age of 17, of Bristol-born Thomas Chatterton is under way to remind people of his extraordinary but often forgotten life, and, perhaps, inspire a new generation of Romantic poets.

The celebration includes the commissioning of new poems based on the deathbed painting of Chatterton by Henry Wallis, which hangs in Tate Britain, London. A comic book relating his life story is being produced, and a competition will be held to design a new monument to him in Bristol.

Andrew Kelly, director of the Bristol Cultural Development Partnership, said one of the main aims of the anniversary celebrations – called A Poetic City – was simply to make sure Bristolians knew about him.

“Despite his accolade by some as the father of Romantic poetry, and the centuries of fascination that he’s held for poets, artists and musicians, he’s largely unknown in his home city,” said Kelly.

Chatterton was born in November 1752. A solitary, precocious child, he spent many hours reading and writing near a tomb in the church of St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol.

He adopted the persona of an imaginary 15th century monk, Thomas Rowley, and produced work – not only poems, but maps, letters, and even fake business accounts – in Rowley’s name.

Chatterton’s death in August 1770 is shrouded in mystery. It has long been thought that he took his own life, but some modern academics believe it was an accident.

Kelly said: “His story raises more themes including artistic credulity and credibility, the role of the fake in art, young artists, arts and mental health, and the nature of celebrity.”

The great Romantic poets became huge Chatterton enthusiasts. “At the time they were writing, Britain was moving towards industrialisation,” said Kelly. “They liked the fact that he looked back to the medieval period, writing under the guise of Thomas Rowley.

“They were influenced by his politics. He was very radical, against the slave trade and kicking against the establishment. There was also the doomed romanticism – his supposed suicide, though the opinion now is that it was accident rather than suicide.”

As well as looking to the past, A Poetic City will touch on issues from Chatterton’s lifetime which are still relevant today, such as young people and mental health, and fake news.

While there is a statue of Chatterton in Millennium Square in Bristol, only the fragments of a monument to him that used to stand at St Mary Redcliffe church survive in a city museum. A competition is to be held to design a new monument, which will hopefully be erected within a few years.

The project will involve the Glenside hospital museum in Bristol, which is based in a former psychiatric hospital and tells the story of mental health care through the ages. The museum’s co-ordinator, Stella Man, said she hoped it could help widen the debate about mental illness and the role art and heritage could play.

Another highlight will be a collection of poems by 12 contemporary writers responding to the Wallis painting. They will be compiled in a book and read in public.

Theresa Lola, the Young People’s Laureate for London, has composed one of the poems, focusing on the window behind Chatterton’s deathbed and wondering why it is open.

Danny Pandolfi, a director of the Lyra Poetry Festival, which has commissioned the work, said: “Chatterton is not someone who is massively talked about or celebrated. He should be.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News