Bristol's D-Day role 80 years ago was 'different but vital'

Everyone knew that D-Day was coming. Where and when was, of course a closely-guarded secret. Everyone in Bristol knew that Bristol was doing its bit. But at the time, only a few senior generals and politicians had any real grasp of how significant Bristol’s contribution was going to be.

If you know anything about the preparations for the great invasion of Europe, you’ll know that the ports on the south coast were busy. You’ll also know that the US Army Air Force was bombing Germany, mainly from airfields in the East of England.

All over England, there were large camps of Allied soldiers training for the big event. Not just British troops, but Americans, Canadians, Free French, Free Poles and many more.

Read next

King and Queen hear moving recollections from Portishead D-Day veteran

Bristol D-Day hero recalls being thrown from ship in explosion that killed 31

But Bristol’s contribution was different, and it was absolutely vital. When we think of D-Day, we usually think of the fighting on the beaches, and the fighting through Normandy in the following days and weeks.

It’s only natural that we tend to focus on the dramatic side of the history, the stories from the sharp end of the fighting, tales of heroism and losses which led to eventual victory. The actual fighting, though, is only half the story – less than half the story, in fact. D-Day would never have been possible without a huge amount of careful planning beforehand.

And there would have been no point in even thinking about planning anything were it not for the output of Britain’s war industries and the even bigger output of the United States. D-Day did not just need men. It needed tanks, fuel, munitions, guns, bombs, aircraft, ships, landing craft, ambulances and much more. Those men needed uniforms personal equipment, tents and food, medical supplies and so on. Including cigarettes – especially cigarettes, in fact.

It wasn’t enough to just manufacture all of this stuff. You had to get the right things to wherever they were needed at the right time and the right quantities. If the people fighting at the sharp end don’t have enough fuel and ammunition, no amount of courage will help. As an American general once said: “Amateurs talk about tactics, but professionals study logistics.”

The story of Bristol’s part in D-Day is overwhelmingly the story of logistics. Bristol’s industries were already playing a significant part in the war effort before America entered the conflict, most notably the Bristol Aeroplane Company. But when the USA came in, things upscaled dramatically.

The city docks, and even more so Avonmouth, were among Britain’s main Atlantic ports. This was where prodigious quantities of American weapons and war materials came to Britain to be stockpiled in readiness for D-Day.

Bristol was a key hub for all of this American equipment – for years afterwards, people would remember open spaces being turned into huge parks for trucks, guns and jeeps. At Filton American servicemen assembled the aircraft which came in via Avonmouth.

In the meantime, the preparations for D-Day went on. Clifton College was taken over by the US Army and it was here that many of the preparations for the Normandy landings were made by General Omar Bradley and his staff in early 1944.

Bradley and other senior American officers stayed at The Holmes, a grand Victorian house on the Downs which had been bought by Bristol University in 1943 but which was now used to accommodate the American brass. It’s nowadays at the centre of the Bristol University Botanic Gardens.

The American leadership chose Bristol as a location for planning because it was away from London, and so, they hoped, further away from the prying eyes of any German spies or Nazi sympathisers. Bristol was also chosen by the supreme commander of the D-Day effort, General Eisenhower himself – to store something very special.

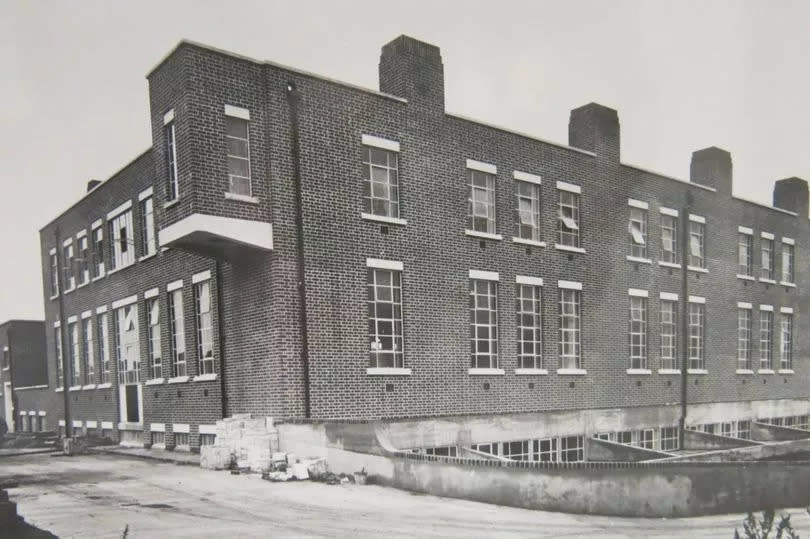

One of those strange-but-true stories about Bristol’s war concerns the new Co-op bakery in Brislington. The Co-op managers had wanted to build a bakery before the war, and the plans were well advanced, but when war broke out, the work had to be put on hold.

Now, the Americans stepped in and paid for it to be built in double-quick time. The only thing was that the Co-op couldn’t have it just yet.

This new building, which to all purposes looked like the ordinary bread factory that it was, was used to store the secret of the invasion. The Germans knew the invasion was coming, but they didn’t know where the Allied forces were going to land. Many German commanders assumed that it would be around Calais, the shortest crossing point between Britain and the continent, but they couldn’t be sure.

Had any German spies taken a close interest in the Brislington bakery, they would have found that its basement air raid shelter was guarded by soldiers with Tommy guns. That’s because it contained some 20 million French Francs which were to be distributed to soldiers at the last minute before Operation Overlord was launched.

But more important still, it had tens of thousands of maps which would be issued to officers. These were maps of the landing beaches and the inland areas in Normandy, not Calais. Had the Germans known of this, they would have known exactly where the landings were to take place.

But the secret was kept safe in Brislington, and the bakery was handed over to the Co-op on the very day the landings started. According to local legend, it baked its first loaves on June 6 1944, the minute the Americans and their maps and French money had left.

In early June, some people had an inkling of what was afoot as a large number of American soldiers had left very suddenly. One lady recalled African-American soldiers billeted in Henleaze giving the children all their English coins. Others returned home to find the American who had been lodging at their house had mysteriously disappeared.

Almost 160,000 Allied troops – British, American, Canadian, Free French and more landed in Normandy on June 6. The fighting in northern France would be bitter for some weeks to come, but Paris was liberated by the end of August, and by then the war’s outcome was no longer in doubt, despite setbacks like the Arnhem campaign or Hitler’s last-gasp offensive in the Ardennes in December.

On June 6, the news was greeted with a great deal of excitement and enthusiasm, but also a lot of trepidation. In one sense though, Bristolians were very lucky in that many of them could do something to help. They rolled up their sleeves to give blood.

At the start of the war, Bristol became the HQ for what was known as the National Blood Transfusion scheme, and a major collection and distribution facility was set up at Southmead Hospital. By 1944, the system was running well, processing huge amounts of blood and plasma, and with huts near workplaces and hospitals for collections. Workers, men and women, at Bristol’s big factories such as Wills and BAC, were now asked to come forward to donate.

As the news of D-Day was sinking in among the civilian population, there was an urgent appeal for Bristolians to make every effort to attend. Workers at the BAC factory, close to Southmead, were particularly encouraged, and medical staff worked into the early hours of June 7 taking donations which would be in France – saving lives – just 24 hours later.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News