Bullied but not broken: How this woman survived years of torment

Kelsey Clarke was bullied for over a decade. She says the effects still haunt her. (Sarah Antle/CBC)

WARNING: This story contains disturbing content and details of suicide.

Kelsey Clarke looked like any other kid. She liked colouring and reading and hanging out with her friends.

But when she went to school, Clarke faced a nightmare that, a decade later, she still hasn't woken up from.

The bullying started in grade one. Name calling, exclusion, and social ridicule marked her days through to graduation.

"High school, I would say, was the hardest time of my life," she said. "I know people say high school is the best years of your life, but I would beg to differ."

During junior high and high school, many of Clarke's days started with a panic attack. She wondered what her bullies would say to her each day as she got ready to leave her house.

"It didn't really matter what I did, what I said, who I was with," she said. "People just sought me out."

It's a problem that kids across Canada face every day.

WATCH | Kelsey Clarke shares her story

Last year, the Kids Help Phone received 4.7 million calls, texts and messages. Kids Help Phone senior director Gayle Browne said 3.6 per cent of those contacts were from Newfoundland and Labrador.

Most of those calls, Browne said, were related to bullying.

"It's ruining lives," Clarke said. "It's taking lives."

Words that stick

Clarke, 28, says her life is much better now. She married her husband, Adam Waterman, in December. She has friends, a job and hobbies. She's comfortable.

But daily and debilitating anxiety is unwanted company that has pestered Clarke since her schoolyard days in Spaniard's Bay.

Behind the contagious smile and bubbly attitude are invisible bruises she's spent her whole life poking at.

She used to ask herself, "If these are the best years of my life, what do I have to look forward to?"

The bullying started when Clarke was in Grade 1, she says, and got worse every year. (Submitted by Kelsey Clarke)

She said people would make fun of her for crying, for being anxious, for her appearance. And though she had friends, no one stood up for her.

"I think I was just an easy target," she said. "My grandmother always told me I was very soft-hearted, so I would take everything personally."

In Grade 10, Clarke was diagnosed with anxiety and depression. At first, she thought things would finally get better because she could get treatment and support.

Instead, her classmates called her "crazy."

For a while, she refused to take her medication for the fear of being ridiculed.

"I was convinced that these people were right," she said.

Clarke grew up before social media became a staple in every child's life, when bullying was still confined to the school and playground. At that time, Clarke said, she would go home from school and find reprieve in her books — an escape strategy she still uses years later.

But as social media became prevalent in her life, the bullying became worse. It was no longer a problem only during school hours.

Clarke was accessible to her bullies 24/7.

"I used to get anonymous statements saying that I was a baby and I cried and no wonder I didn't have friends," she explained.

Kelsey Clarke and her husband, Adam Waterman, married in 2023. She says she always hoped to meet someone as supportive as him. (Submitted by Kelsey Clarke)

She would tell them, "Ignore me if you don't like me."

"It's really hard to ignore you when I hear your fat stomping down the hallway," one of the faceless replies read.

Those taunting voices dug deep into Clarke's psyche.

"Those are your cognitive years," she said. "Your brain is developing and you're being told you're fat, you're ugly, you're a terrible person, and it just stays there."

"And sometimes I still have those feelings," she said. "Am I that person that they claim I am?"

The comments stuck to Clarke's mind like a psychological leech. Her high school years were coloured by self-doubt and fear, and she still feels the effects today.

"I still deal with a lot of confidence issues. I'm really not a confident person. I fear people's opinions. I have trouble making friends. I have trouble picking up new hobbies, doing new things because of that fear of being ridiculed."

Clarke still sometimes wakes up in the middle of the night with nightmares.

"They haunt me," she said.

A parent's nightmare

Clarke's mother, Paula, found out about the bullying from a family member who saw some comments on a Facebook post calling her daughter fat and ugly and telling her to kill herself.

"Kelsey got a heart of gold," said Paula Clarke. "A beautiful young woman. She was always beautiful and … to say to someone kill yourself… like, it shouldn't be."

Clarke said when she told her mother and teachers what was happening, nothing changed.

"It's your word against theirs," she said. "They say nothing happened. You say this happened. I can't prove it."

Her mother lived in fear.

"There was days I'd come home from work and I was afraid to go up to her bedroom. Because I really thought one day she may commit suicide," she said.

"The cruellest thing in the world is knowing that your child is hurting."

Paula Clarke says she was terrified to come home from work because she feared Kelsey would commit suicide. When her daughter graduated, she says, she was relieved. (Sarah Antle/CBC)

"I just didn't know what to do at first because it was so severe and she'd come home every day crying and she had no friends. I was her best friend," Paula Clarke said. "I wanted to be in her place, really."

Browne said 75 per cent of youths who used the Kids Help Phone last year struggled with telling someone for all kinds of reasons.

"Going to your teacher, talking to your parents, telling your other friends, It can be both, you know, shameful, embarrassing, could make things worse," she said.

Is bullying getting worse?

With anti-bullying campaigns like Pink Shirt Day, awareness of the problem has never been higher. So why is it still an issue?

"On a national scale right now, you know, bullying I would say is one of the things that's really impacting our young people quite significantly and has been for quite a while," Browne said.

And according to the data, bullying is changing: it's happening online, it's happening earlier, and it's happening all the time.

Browne said the most predominant group the Kids Help Phone hears from is ages 14 to 17, but the statistic is getting younger.

She says social media is "100 per cent, without a doubt" making bullying worse, noting more callers are talking about social media and cyberbullying.

"Your bully's right there with you in your pocket, in your hand, whatever. And then that bully, that person who's harassing you, feels a bit safe and protected behind a screen.

"It can be really relentless for young people.… That kind of harassment can go on all night, all year, all day in your home, in your safe place."

Bret Holfeld, a psychology professor at Memorial University's Grenfell Campus, conducted a cyberbullying-focused study of 900 school-age children in Newfoundland and Labrador in 2023.

Holfield said the research points to a paradigm shift in what bullying looks like to kids. By Grade 6, he said, 90 per cent of the children surveyed had a smartphone.

Holfeld said it's hard to tell if the problem is getting worse or just changing. With so little data available on bullying statistics in the province, there isn't much comparable data.

"Certainly there's more avenues and opportunities to engage in the behaviour than ever before. If you really wanted to engage in the behaviour and direct it at certain individuals, there's way more ways to do it than ever before."

Kelsey Clarke didn’t know what to do when she graduated from high school. A decade later, she still struggles with the effects of the years of bullying. (Submitted by Kelsey Clarke)

And bullying behaviour is trickling down to younger kids, he said.

"What we used to see in Grade 7 and 8, we're now seeing in grades, like, 4 to 6," he said.

The survey asked kids about being cyberbullied and about perpetrating bullying.

"The rates of cyberbullying were around 10 per cent and rates of cybervictimization were around 30 per cent. That's with the direct questions, and with those rates, there didn't seem to be a difference across grade or gender."

But when researchers asked more indirect questions, the victimization rates were higher.

Those questions included whether respondents had had embarrassing pictures posted of them online, been excluded online, or had other experiences characteristic of cyberbullying.

"There is some variability across the items, but the most frequent experience was being excluded or left out online, and that was over 50 per cent of kids," he said.

And the longevity of the effects of bullying — the effects Clarke still struggles with today — is a no-brainer, Browne said.

"Anything that's happening to you in your childhood, in your developmental years has a lasting impact, right? We know that."

The aftermath

For Clarke, her grandmother, Martha Sheppard, got her through.

"She was one of the most important people, still is one of the most important people in my life. She's no longer with us, but she always had my back," Clarke said.

"She always had calming words. We would drink tea together and play board games and watch, like, The Price is Right and I'd forget about it when I was with her sometimes."

But she knows the mental health issues she deals with as an adult are directly correlated to how she was treated in those locker-lined halls.

Clarke's mother marvels at her strength.

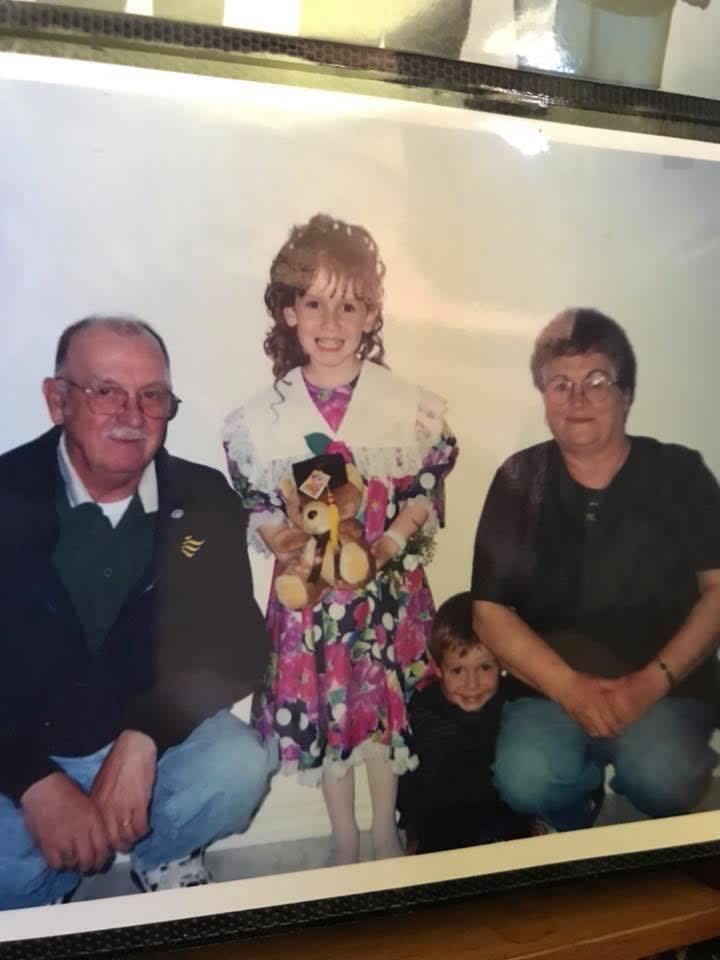

Kelsey Clarke says spending time with her nan, Martha Sheppard, was one of the few escapes she had from bullying. She's pictured here also with her grandfather Absalom Sheppard and brother, Nicholas Clarke. (Submitted by Kelsey Clarke)

"If I was Kelsey, I don't think I would have made it through it," Paula Clarke said.

And she almost didn't.

"I was ready to end it all and just be like, free of it. Maybe find peace finally," Kelsey Clarke said.

"But I had hope."

Clarke hoped things would get better, that she would find friends who wouldn't leave her, and that she would find a partner to support her.

Her advice to anyone being bullied is to hold onto, at all costs, whatever gives you hope.

"Ignoring people who are bullying you is so hard because those little pieces, they get in your brain and they grow roots," she said.

Life moves on, she said. Even if someone's not ready to move on, they should just keep trying.

"It's not the end of everything, even though it might feel like it."

If you or someone you know is struggling, here's where to get help:

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News