California professor repeats history with Pulitzer

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — The first time historian Alan Taylor won a Pulitzer Prize, he had just returned to his office at the University of California, Davis from a tennis match when the telephone started ringing with congratulations and interview requests.

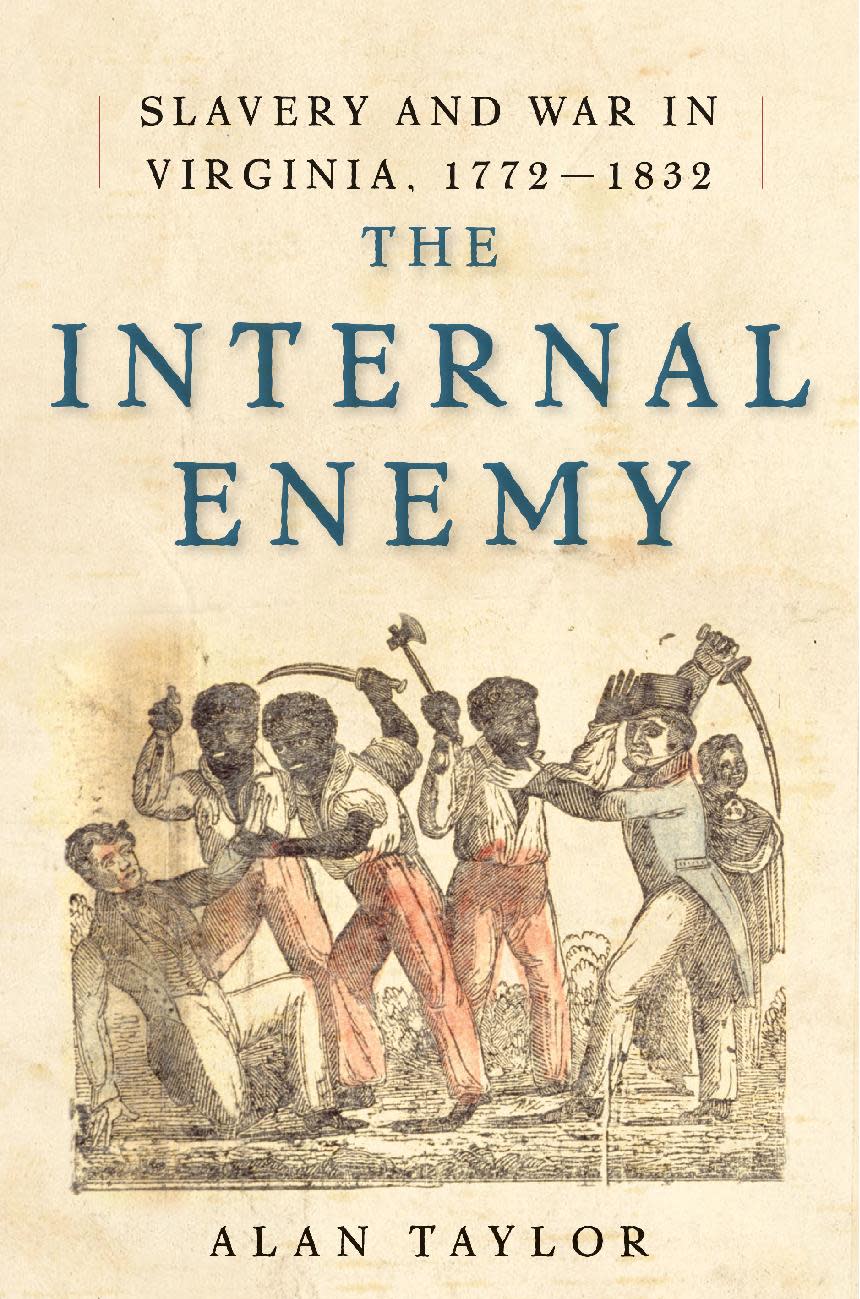

Eighteen years later, the surprise and slight panic Taylor felt repeated themselves when the 58-year-old professor of early American history got the news Monday via a barrage of emails that he had a won a second Pulitzer for "The Internal Enemy," his book about the role escaped slaves around Chesapeake Bay played in the War of 1812.

"It's still stunning news," Taylor said in an interview from a Philadelphia bed-and-breakfast where he was preparing for a lecture and dinner with colleagues. "I'm on the road right now, getting ready to do a talk tonight, so not in an optimal setting to field all this. Not that I'm complaining."

Taylor, a native of Portland, Maine, who has been a professor at Davis since 1994 and will be transferring to the University of Virginia in August, earned his first Pulitzer for history in 1996 for "William Cooper's Town," which used the life of 19th Century novelist James Fenimore Cooper's father as a lens for the nation's early years.

He stumbled upon the kernel for his most recent book, published in September, in Nova Scotia a dozen years ago while researching the relationship between Canada and the U.S. and found records of local African American refugees who had fled north after the War of 1812.

Taylor eventually located letters in Maryland and Virginia "that revealed this extraordinary human drama." He finally eked out enough time amid his teaching and research duties to focus on "The Internal Enemy," which was a finalist for the National Book Award and he hopes will find a broader audience with the Pulitzer's influence.

"I try to write in a way that will be accessible to a broader public, and I try to do the right thing by the people I write about. And I think I have a broad definition of who matters in history," he said. "We could probably do more in general as historians with the more common people, particularly with people about whom we know fairly little, particularly enslaved people."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News