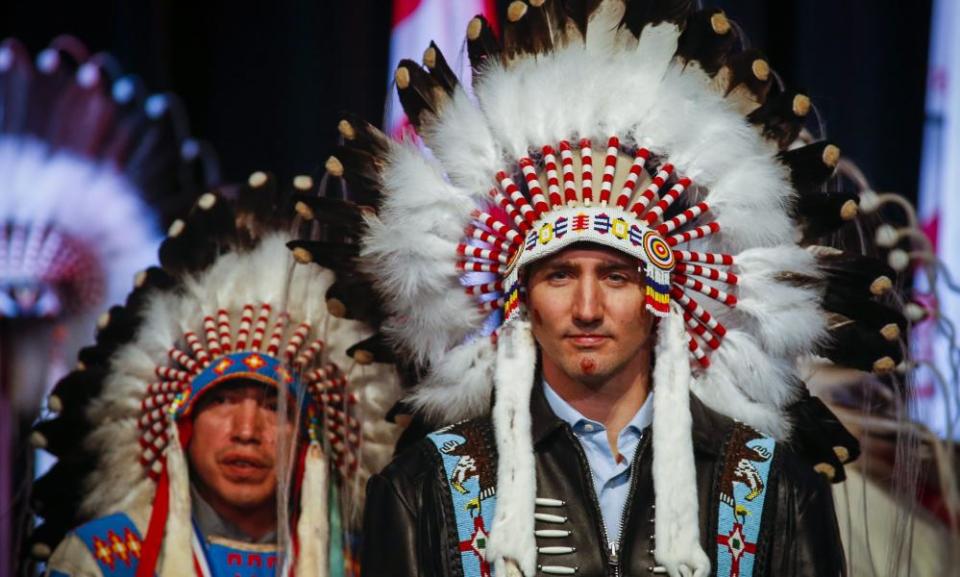

Canada indigenous leaders divided over Trudeau's pledge to put them first

When the Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, came to power in 2015, he pledged to mend the broken relationship with indigenous peoples across the country, recognizing that “the rights of First Nations in Canada are not an inconvenience but rather a sacred obligation”.

In speech to the House of Commons this week, he admitted the promise has gone unfulfilled.

The address came in a turbulent week of rallies and protests after farmer Gerald Stanley was acquitted by an all-white jury in the murder of Colten Boushie, a young Cree man.

“Too many feel and fear that our country and its institutions will never deliver the fairness, justice, and real reconciliation that indigenous peoples deserve,” said Trudeau in his address.

Indigenous leaders were cautiously optimistic over the announcement.

“I welcome his words. It’s an entire paradigm shift in how the crown will deal with our rights and title,” said the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Perry Bellegarde. “It’s going to be done in a true partnership and that’s going to be the key.”

Natan Obed, the National Inuit leader, said that the overhaul “requires systematic recognition and redress for outstanding human rights violations”, and that “respect for Inuit as rights-holders – not as stakeholders” is critical for the success of any talks moving forward.

But not everyone was “wooed by [Trudeau’s] great words”, said Pam Palmater a prominent Mi’kmaw lawyer, professor and chair of indigenous governance at Ryerson University, who called the speech a way to distract from the negative press surrounding the Stanley verdict.

Her biggest concern with the speech is what Trudeau left out. “The question that he never talks about in any of speeches or announcements is lands, resources and power. Those are big ticket items that are the crux of reconciliation,” she said. “He’s staying well within the realm of the superficial.”

The proposed overhaul marks the largest change to legal relationship between indigenous peoples and the federal government since Section 35 of the Constitution Act – which guarantees rights to First Nations, Métis and Inuit – enacted 36 years ago.

Despite numerous reports and commissions to determine a path towards indigenous self governance, the pace has remained frustratingly slow, says Naiomi Metallic, a law professor at Dalhousie University.

“There’s always this dance between the courts and the federal government, with indigenous people caught in the middle.”

For years, one of the only avenues for indigenous peoples to have rights confirmed is through the court system – a costly, drawn out process that costs millions of dollars.

Trudeau himself admitted the failures of past governments, lamenting the disregard for court-affirmed rights for indigenous peoples.

“Indigenous peoples were forced to prove, time and time again, through costly and drawn-out court challenges, that their rights existed, must be recognized and implemented,” he said.

For communities that have lived those extended court battles, the news was long overdue.

“As Tsilhqot’in, we have pushed for over 150 years for change in this country and progress is far too slow,” said Chief Joe Alphonse, the tribal chairman of Tsilhqot’in national government in central British Columbia.

The Tsilhqot’in were forced to fight an expensive, decades-long battle with the provincial government over title rights after land they had long hunted was slated to be logged.

Their struggle culminated in a 2014 victory at the supreme court of Canada – part of

30 year string of court battles fought by indigenous communities for recognition of pre-existing rights.

Palmater and others worry that instead of fixing a broken system, the Trudeau government is developing a new one that effectively prevents and discourages indigenous groups from using the courts to win back pre-existing rights the government has refused to recognize.

“Instead of doing a nation-wide review of Canada’s laws, which are the problem, he’s going to create a new set of laws that will define and effectively limit the scope of aboriginal and treaty rights. And that’s the part that most people don’t hear,” she says. “They’re going to try to rush and legislate and define and limit aboriginal and treaty rights so that there isn’t consent from indigenous peoples. That’s a huge concern.”

She worries the speech may lull Canadians into thinking a messy tangle of laws, promises and treaties might easily be resolved – all before the next election in 2019.

“It’s almost easier to fight the bully government than it is the oozing ‘we love you so much’ government,” she says. “But the facts of the matter, and their actions, speak far different.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News