Carbonara, English muffins, Caesar salad and other dishes that aren’t from where you think they are

Sacrilegio! Italian food expert Alberto Grandi has rocked the Italian gastronomic world by calling into question the origins of some of their sacred cows – and pasta dishes, desserts and cheese.

This isn’t the usual pedantry pointing out that the Chinese may have invented pasta first or that tomatoes didn’t reach Europe until the 16th century, so pomodoro sauce is a relative newcomer. No, Grandi, the author of the Italian bestseller Denominazione di Origine Inventata (“Invented Designation of Origin”, a play on the highly regarded Protected Designation of Origin or PDO rating) is busy toppling more recent – and arguably more cherished – golden calves.

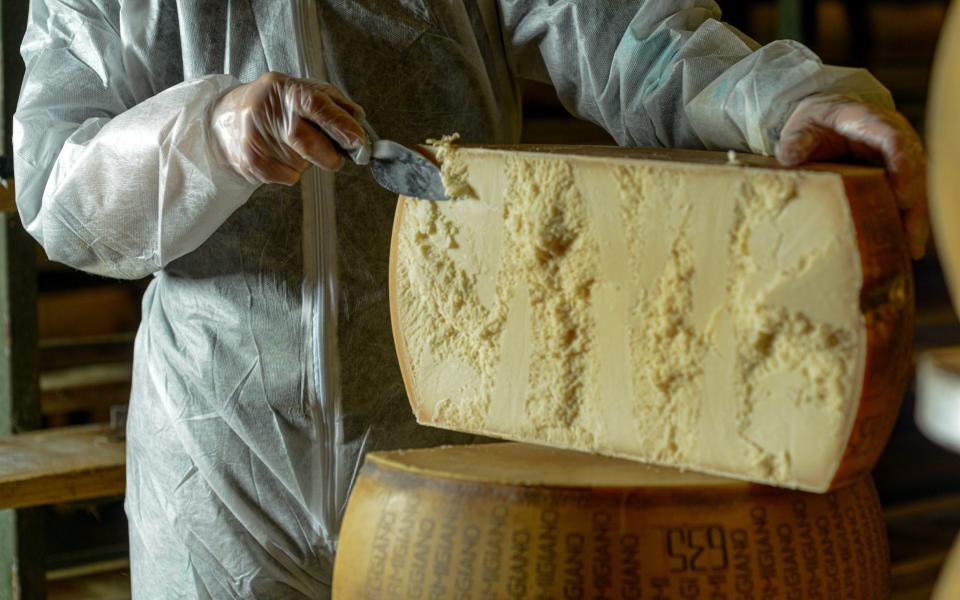

Take parmesan, the king of Italian cheeses and the bedrock of countless dishes, with its savoury flavour and crystalline texture. Grandi says that until the 1960s parmesan was not a huge hard cheese in wheels weighing 40kg, but a softer, semi-hard cheese in black wheels of just 10kg.

It’s still made in a similar way in Wisconsin, where Italian immigrants have preserved that older style, while still calling it parmesan – much to the disgust of Italian parmesan makers, who have a monopoly on the name in Europe but not the States.

Then there’s panettone, which feels like a centuries-old tradition. In fact the light Italian bread, an answer to our heavy dark Christmas cake, was invented by manufacturers Motta in the 1920s. It remained largely an industrial product until the 1970s, when independent bakeries began making artisan versions.

Other foods are more disputed, like tiramisu. This most Italian of trifles may have been invented in a Treviso brothel in the early 19th century, if you believe the Accademia del Tiramisu. But they have skin in the game, or at least marsala in the marscapone. A more plausible story has it originating in a Treviso trattoria in 1969.

Pizza is in the firing line too, as Grandi points out that it was a southern Italian street food of the poor until after the Second World War, and pizza restaurants are an American invention.

Pasta carbonara, possibly the pasta dish that dogmatists get most wound up about, was invented in 1944 when Italian chef Renato Gualandi cooked it up for guests, including Harold Macmillan and members of the US army. If you are an Italophile you may want to sit down here – the recipe used bacon not guanciale, the cured pork jowl that is considered the sine qua non of a true carbonara by purists.

Mamma mia – it seems that the creation of the Italian food tradition, with its hard-line purist approach that’s been nicknamed “gastronationalism”, came out of a need to reclaim the Italian identity after the deprivations of the first half of the 20th century. But Italian dishes aren’t the only ones with invented origins. Gastromythology is all around – but if it tastes good, do we care?

Culinary origins contested

Pavlova is Australian: fiction

Both Australia and New Zealand lay claim to the meringue, cream and fruit extravaganza, with the legend that it was created during one of Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova’s tours of the Antipodes in the 1920s. New Zealand seems to win out with the first “Pavlova cake” recipe that fits the bill being published in 1929, while Australia lags behind with its version making it into print in 1935.

But could they both be wide of the mark? Quibblers point out that pavlova-like meringue cakes were commonplace in Europe long before the 20th century, and a recipe for “strawberries pavlova”, a frozen pud rather than meringue, had been published back in 1911, with a pavlova layered jelly in 1926. So our friends Down Under didn’t invent the recipe, or the name – but they were the first to put the two together.

Vichyssoise is French: fiction

An elegant chilled leek and potato soup, vichyssoise is French chic in food form. Except it’s American, invented by the chef Louis Felix Diat at the Ritz-Carlton in New York, where it was an antidote to the sweltering summer temperatures in Manhattan.

Diat was born in France, not far from the spa town of Vichy, and the name is a tribute. However the French have distanced themselves from the recipe, with the first Francophone mention of the soup, in La Revue Culinaire of 1923, classifying the soup as American.

English muffins are actually American: fiction

Americans have laid claim to “English muffins”, and you’ll find countless stories online that they were invented by immigrant Samuel Bath Thomas in 1880 and subsequently sold in his New York bakery. These are balderdash.

Yes, it’s true that muffins of the bread type (as opposed to true American muffins, a sort of bloated cup cake) fell out of favour over here in the 20th century, while thriving in Stateside supermarket aisles.

But versions of the nursery rhyme “Have you seen the muffin man” date back to the 18th century, and food writer Hannah Glasse has a precise recipe in her 1747 bestseller The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy, right down to instruction to split the muffin with your hands not a knife or it “will be heavy as lead”.

Still not convinced? Oscar Wilde has quintessential Englishmen Jack and Algernon squabble over the muffins in The Importance of Being Earnest, first performed in 1895. “Good heavens! I suppose a man may eat his own muffins in his own garden,” says Jack. Without being told they are American, he might have added.

Caesar salad is American: fiction

The enticing concoction of cos lettuce, parmesan, egg and croutons might be the most American of lunch dishes, but it’s not a US invention. The first Caesar salad was whipped up in 1924, in Tijuana, just over the border with Mexico, by Italian-born restaurateur Caesar Cardini.

The original recipe included a lightly cooked, not raw, egg, no anchovies, and parmesan cheese – presumably the softer, moister kind that Grandi refers to, not the ultra hard cheese we use today.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News