‘Carol Doda Topless at the Condor’ Review: Her Breasts Shocked America, Her Documentary Plays It Safe

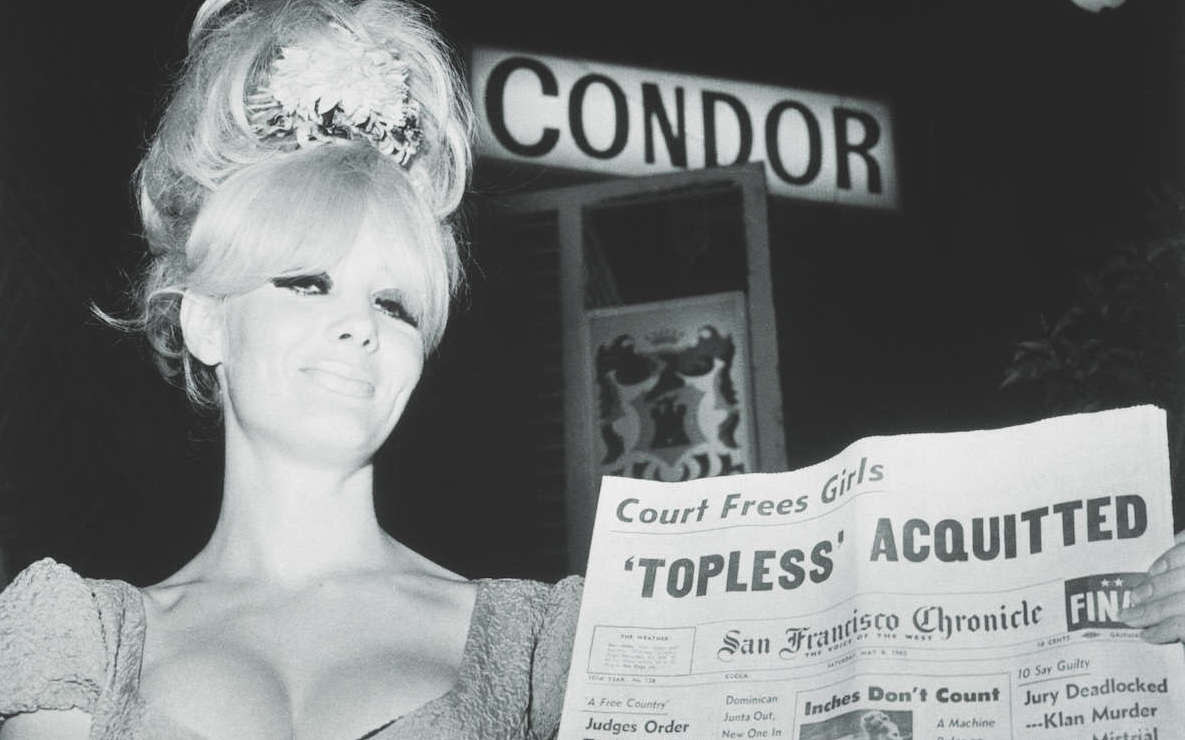

It’s funny to think that the birth of our country’s strip clubs traces back to a total drip like Barry Goldwater, but that conservative also-ran was in San Francisco to accept the Republican Party’s nomination for president when — on the night of June 19, 1964 — a lounge singer by the name of Carol Doda decided to show the city what she thought about his “traditional American values.”

Okay, technically it was PR maven Davey Rosenberg who had the idea for Doda to descend from the ceiling of the Condor Club in a monokini with her nipples on full display, and the fact that Goldwater was in town for the RNC was more of a coincidence than anything else, but those pesky facts didn’t stop Doda from stealing the Republicans’ thunder and becoming a political icon all her own. Goldwater’s sons even came to see Doda’s show before they returned to the campaign trail, blissfully unaware that the half-naked blonde they watched sing atop a baby grand piano would soon be regarded as a symbol of the women’s liberation movement their father was promising to stop in its tracks.

More from IndieWire

'Late Night with the Devil' AI Usage Sparks Debate: Fair or Foul?

'Free Time' Review: A New Yorker Chases the Ever-So-Elusive Work-Life Balance in Dry Comedy

Not that Doda ever claimed to be much of an activist. “I wanted to be in show business,” she said, “and I didn’t know any other way than showing my business.” Her business — in both senses of the word — would soon grow bigger than she had ever imagined.

Save for the liquid silicone injections that swelled Doda’s “fried egg” B-cups into a pair of rock-hard DDs (Doda became known as “two of San Francisco’s most famous landmarks”), all of this is covered in the opening minutes of Marlo McKenzie and Jonathan Parker’s “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor,” a fittingly overinflated film that spends the rest of its runtime filling in the local history as it halfheartedly debates whether Doda surrendered to the male gaze or if she hijacked it for her own purposes of self-expression. This documentary tribute is far too fawning and affectionate to engender any real discussion about that (while the movie’s talking heads are mostly people who knew Doda firsthand, even the younger academics interviewed here credit her as an unalloyed hero), but also too vague in its praise and presentation to make anyone rethink their position on sex work as a form of social empowerment.

Like so many pieces of light, streaming-era infotainment, McKenzie and Parker’s film is petrified of becoming too substantive for people to watch with one eye while the other looks at their phone, and so “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” would rather blur itself into a Rorschach Test than make a more full-throated case that feminism can take any number of forms. Too safe and soft around the edges to meaningfully capture the spirit of an unsung American pioneer, this documentary is more valuable as a niche time capsule — one that vividly remembers a moment in history when North Beach nightlife was at the center of the universe.

Doda died in 2015, and so McKenzie and Parker are left to create an impression of their subject from the people who knew her. The trouble with that — if also the greatest source of this film’s squandered potential — is that no one really did. “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” features interviews with just about every living person who was part of that scene (you can tell that many of them are speaking on camera about it for the first time, eager to ensure their memories won’t die along with them), and they lend this movie an overabundance of local color.

We get deep dives into the dance crazes that informed Doda’s act, nebulous tangents about the interplay between risqué night clubs and racially integrated music acts, and even a history lesson on how Doda inspired a short-lived fad of topless businesses throughout San Francisco (topless shoe shine, anyone?). Through it all, however, Doda can’t help but seem like more of a social conduit than she was a woman unto herself. The filmmakers simply concede to the fact that Doda was a private soul (the press notes mention that she once backed out of a biopic at the last moment because of cold feet), and perhaps a lonely one as well, and they take that as an excuse to ignore the person behind the breasts. The only insight the directors manage to elicit from Doda’s ex-boyfriend? Her boobs were heavy.

It’s mentioned that Doda had two kids prior to her topless career, but her decision not to raise them goes unexplored as it pertains to her progressive interpretation of modern womanhood. She “never felt like a mother,” but did she feel a political justification in resisting that role? It’s a relevant question in a film that frequently wavers about whether Doda was subversive out of personal interest or financial necessity.

She always claimed that she was in it for the money, and that if she didn’t keep raising the stakes — going bottomless, getting 44 silicone injections, etc. — some other girl would, but that doesn’t entirely square with the iconoclastic spirit of a woman who claimed she was “too stupid” to realize what she was doing, only to turn herself into a media superstar who leveraged her local renown into national fame, received a Harvard Business Person of the Year award, and gave Tom Wolfe a run for his money when he profiled her for “The Pump House Gang.”

At the very least, it seems safe to assume that Doda wouldn’t mind how this documentary casts her as a quasi-deliberate revolutionary, but McKenzie and Parker lack the intel to see any deeper into Doda’s bimbo savviness, just as they lack the ambition to explore whether intentionality even matters when it comes to changing the world. Because the film offers so little detail into the specifics of who Doda was, it perversely makes it that much harder to contextualize Doda against the backdrop of the history she helped to shape. The one thing that’s clear is that Doda loved to be seen, and for that reason — as much as any other — it’s easy to imagine that she would love “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” for projecting her image into the 21st century, just as it’s easy to appreciate McKenzie and Parker for making that happen. But if being seen was all Doda needed to help spark the sexual revolution, this movie about her doesn’t seem to realize that it would have to clear a higher bar in order to be considered a success.

Grade: C

Picturehouse will release “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” in theaters on Friday, March 22.

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News