Charles Spencer Reveals Childhood Trauma in Heartbreaking Account of His Boarding School Experience (Exclusive)

In an exclusive excerpt from his new memoir 'A Very Private School,' Spencer opens up about enduring abuse as a young boy at the elite Maidwell Hall

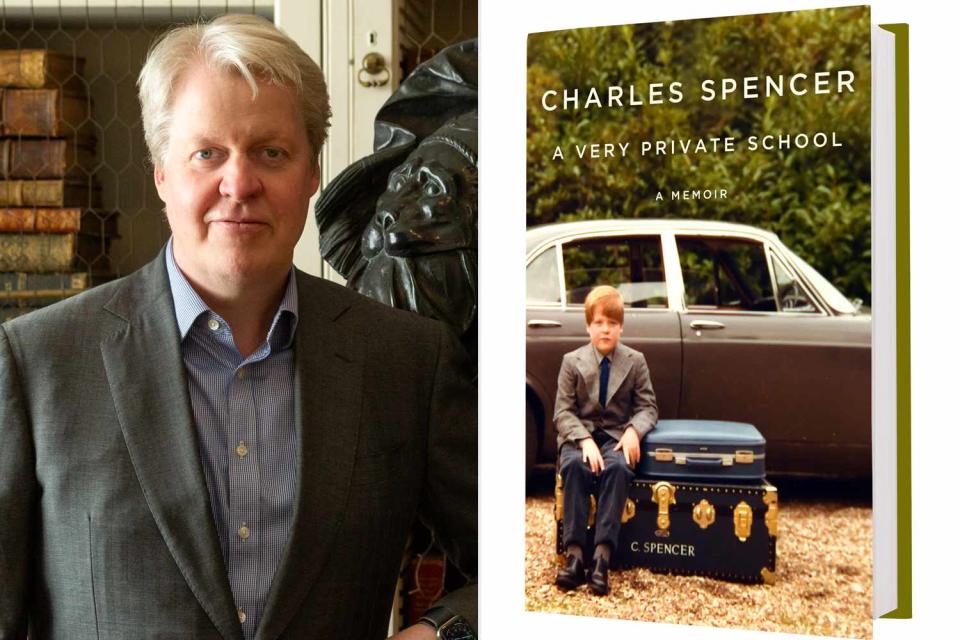

Ian Greeland; Simon and Schuster

Charles Spencer in 2021 at his ancestral home, Althorp (left). Right: His new memoir, 'A Very Private School.'In his new memoir, A Very Private School, Charles Spencer shares a harrowing account of his brutal boarding school experience as a young boy.

The historian and younger brother of Princess Diana revisits his childhood at Maidwell Hall, an elite English boarding school, offering a candid firsthand exploration of the culture of cruelty ingrained within its walls. Throughout his memoir — which will be released March 12 — the 9th Earl Spencer delves into the lasting impact of his experiences, including instances of abuse.

In PEOPLE's exclusive excerpt below, Spencer, 59, vividly recalls the abandonment he felt when he was sent away to school at the age of 8 and reflects on the enduring effects of the trauma on his life and relationships.

Charles’ charmed childhood was rocked by the abandonment of his mother, Frances Shand Kydd, who left her husband for another man and went to live in Australia for six months.

When my mother’s older sister, Mary, pointed out that such a protracted time away would weigh against her in a custody battle, my mother replied, “But when you think about it, what does it matter? All four of my children will be in boarding school in five years’ time — when Charles goes away. And then I will have equal time with each of them, in the holidays, anyway.” It’s a calculation that makes sense when your brain is drunk with love, and when your standard for parental engagement is based on the traditionally distant model of the British upper classes.

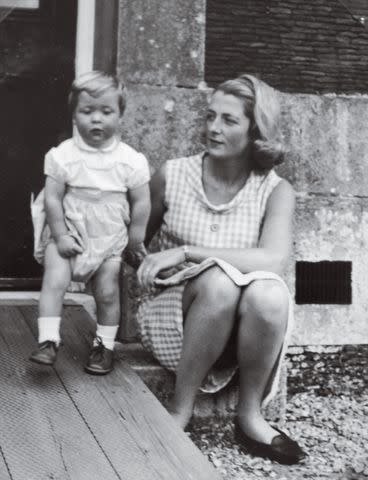

©Earl Spencer

Charles Spencer at age 2, with his mother outside their family home of Park House.At the age of 8, Charles was dropped off at Maidwell Hall by his father John Spencer, 8th Earl Spencer.

I felt exhausted and sick. I knew that, however inconceivable the prospect seemed, my father was on the point of abandoning me. My sister Diana had countered her first-day despair on reaching boarding school with the heroic challenge: “If you loved me, you wouldn’t leave me here.” But she had been a girl of 10 and I was a boy of eight, and I lacked the words or the maturity to express the shocked sense of betrayal that was chewing at me from within.

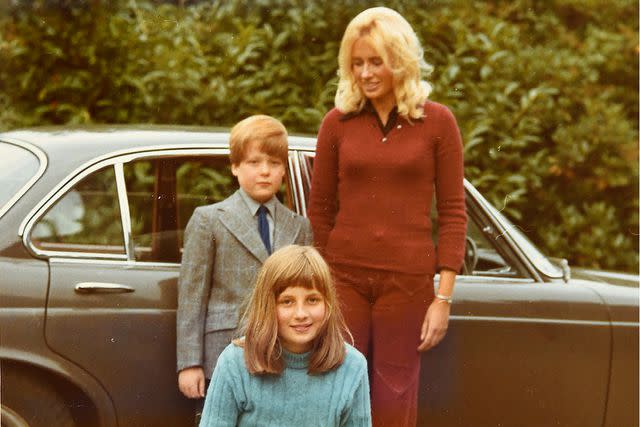

©Earl Spencer

Charles Spencer with his sister Diana (seated) and nanny Mary Clarke as he headed off for Maidwell Hall in 1972.Charles quickly realized that certain students would suffer daily beatings — sometimes with a cane on bare buttocks — by Headmaster Porch, whom the pupils nicknamed “Jack.”

Soon after I arrived at Maidwell, I learned that the school never had a victimless day. After tea, at 10 minutes to six, it would be the turn of at least half a dozen of us boys to disappear into the dimly lit corridor that led from the side of the school kitchen to the private wing, where the Porches had their set of rooms . . . When your time finally came, you were ushered forward by the deputy head boy. As you shuffled into the gloomy study, your eyes acclimatized to find Jack seated, devoid of compassion, ready to dispense physical pain, the quiet blaze in his eyes betraying his inner gratification . . . The head boy witnessed these nightly beatings while standing in the shadows behind the headmaster, his job to record on the school list who had been beaten, for what, on which day, and how many times.

©Earl Spencer

Charles Spencer in his Maidwell "Sunday best" suit in 1972.During one of his nightly patrols, the headmaster caught Charles and his classmates in their dormitory talking after “lights out.”

The handle on the dormitory door slowly turned. Terror. It was Jack. We lay still, hoping to pass for sleeping innocents. Jack put the light on. “Who was talking?” he asked, his low voice choking with excitement, as he sat down on the nearest bed. Four hands went up, including mine. He beckoned us toward him as he flicked a slipper into his right hand. One by one, we were upended on his knee and given swinging blows to the buttocks before being pushed away. I’d been beaten with a slipper several times by him already by now, during his post-tea rituals, but that had been through my trousers. Pajama bottoms presented no protection, and the pain was shocking in its intensity.

©Earl Spencer

Charles Spencer helps clear hurdling fences after Sports Day at Maidwell in 1975.At the age of 11, Charles was groomed and sexually abused by a 19 or 20-year-old assistant matron at the school.

She sat on the side of my bed. She was smiley, kind and chatty. I found it exciting to have such an easy interchange with a member of staff. She talked about things that mattered to me. In the hard, male environment of this traditional boys’ boarding school, where I missed my mother terribly, this calculated deployment of feminine warmth couldn’t fail to entrance, beguile and ensnare me . . . [She] seemed to have an unofficial hierarchy among her prey: We learned, from our secret conversations, that she chose one of us each term to share her bed and would use him for intercourse . . . She added me to the second rank of her victims: those she intimately touched . . . The effect of what she did to me was profound and immediate, awakening in me basic desires that had no place in one so young.

During what he describes as “one of the lowest points” of his life in his early 40s, Charles attended an intensive therapy program focused on processing childhood trauma.

My second marriage had followed the first into failure, leaving two more of my offspring as children of divorce. Feeling beaten, I decided to tackle whatever was attracting partners unsuited to me, and me to them, so the pattern could end. I sought professional help, assuming that something fixable was wrong with me.

©Earl Spencer

Charles Spencer with his sisters (from left) Diana and Sarah, their nanny Sally Percival and his sister Jane on the grounds of Park House in 1969.Writing this book helped him come to terms with his past.

When looking at the wreckage of my first and second marriages, I learned early in therapy that being sent away to boarding school at eight years of age meant that I had next to no understanding of intimacy. It is an almost inevitable consequence of the trauma of which homesickness was the most obvious symptom. Equally, I became highly reactive, so that any slights or threats of abandonment jolted me into “fight or flight” survival mode. I am certain that some things died for me between my eighth and thirteenth birthdays, when in Jack’s care. Innocence, trust, joy — all were trampled on and dismissed in that outdated, snobbish, vicious little world that English high society constructed, endorsed and then handed over to the care of people who could be very dangerous indeed.

From A Very Private School by Charles Spencer. Copyright © 2024 by Charles Spencer. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News