Chipmunk soul and pink Polos: The College Dropout is a tragically distant snapshot of Kanye West’s genius 20 years on

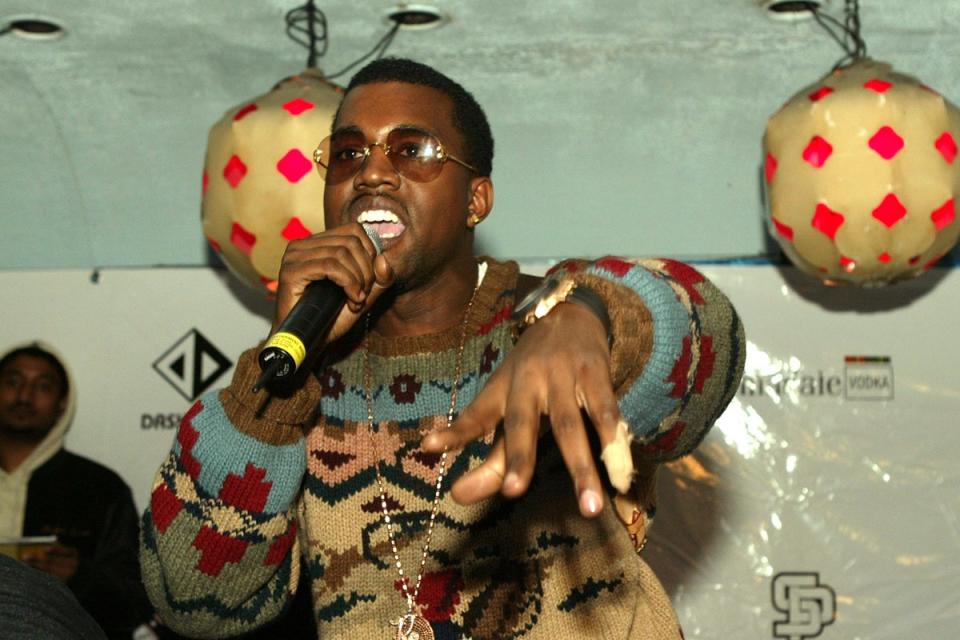

In the year 2024, it’s all but impossible to separate the mythology of Kanye West from the man himself. But long before Ye became a constant lightning rod for controversy and the subject of countless culture wars, he was Kanye: a kid with a daydream, who hustled non-stop to bring his 2004 debut album The College Dropout into the world. Regardless of the parts of Kanye’s legacy that have soured, that instantly iconic album remains sonically fresh. It’s a testament not only to his deft ear for samples, but the overarching creative vision that set him apart from so many of his peers. As the album turns 20 today, its warm chipmunk soul sound, which became Kanye’s early signature, lends itself naturally to the soft glow of nostalgia, evoking a timelessness that’s only sharpened with age.

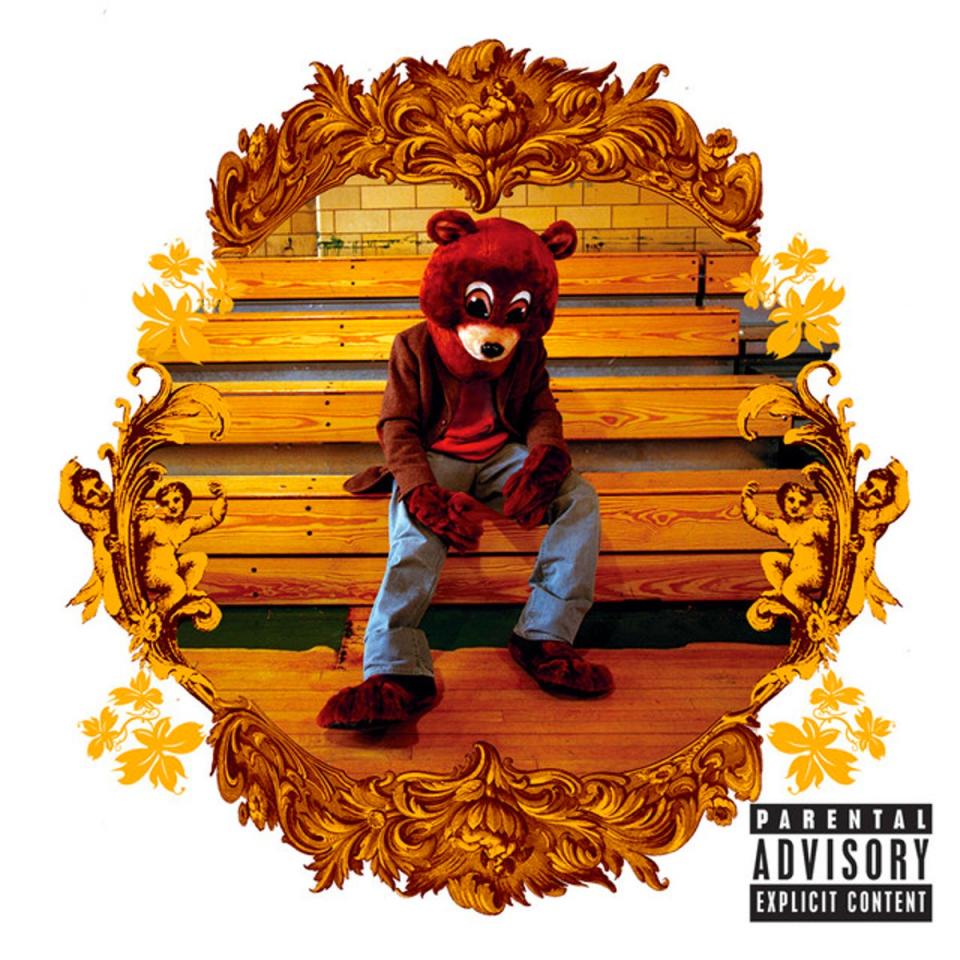

Kanye would develop a singular ability for alienating his audience, but in his early years, he presented himself as a much more relatable and accessible figure. In a retrospective for Noisey, Craig Jenkins described the album’s release as “a watershed moment in 2000s rap history where the nerds stormed the school to seize control from the jocks”, positing Kanye as an awkward polo-clad Peter Parker next to the alpha supermen who dominated the rap game at the time. The very title of The College Dropout and its satirical motif of tongue-in-cheek school spirit – the album cover sees Kanye slouched on the bleachers wearing the head of a bear mascot costume – frames its maker as something of a lower-middle-class everyman. More than a major label rapper, he comes across as an average guy who works a dreary retail job, racks up credit card debt, and disappoints his parents.

For all the braggadocious gymnastics and attention-seeking, Kanye readily presented himself as an imperfect protagonist, frenetically mediating between his id and his superego. He believes in Jesus, but he’s hardly pious or penitent, and he struggles against temptation on the anthemic “Jesus Walks”. He astutely deconstructs the trap of a material culture, but still gives in to the temptation of buying shiny new things. The early Kanye could drop knowledge on a level on par with the most perceptive “conscious” rappers, like Common and Talib Kweli, who appear on the raucous stoner anthem “Get ’Em High”, but instead of scolding from on high, he generally indicted himself along with the system – a sinner seeking forgiveness rather than the outright preacher he would later become.

As he put it on the slam poetry-influenced “All Falls Down”: “We all self-conscious/ I’m just the first to admit it.” The College Dropout does still exhibit the self-indulgence and overconfidence that would become Kanye’s defining traits, but what separates it from the blockbuster bloat of The Life of Pablo (2016) or Donda (2021) is a cohesiveness and intentionality to both the sequencing and the songwriting. It’s carefully considered rather than rushed under the pressure of a deadline.

The hard work and sacrifice that Kanye put into The College Dropout was central to the autobiographical mythos he constructed, as he tells us of “making five beats a day for three summers” just to get noticed. As fellow Chicago rapper GLC put it in an oral history of the album for Complex, “Whenever you heard a new Kanye record, it came from frustration because no one was paying him attention. That’s why it was so good.” On album closer “Last Call”, he breaks down the record’s long journey to fruition in an extended 10-minute outro that functions like a behind-the-scenes director’s commentary, dictating his own origin story in stone before anyone else could write it for him.

A central part of that legend is the infamous 2002 car accident that informs not just the narrative of breakout single “Through the Wire” but his strained vocal delivery on it, as Kanye – through the pain of a jaw wired shut – shows his sceptics just how hard he’ll fight to be heard. The noticeable imperfection of Kanye’s voice made him feel more human, in some ways prefiguring the way he would later use the alien textures of autotune to express a feeling of isolation on albums like 808s & Heartbreak (2008).

As a debut, you can very much hear Kanye learning to find his literal voice on The College Dropout. Tony Williams, his first cousin and a frequent collaborator, described the album as “musically honest” because of how new everything was to Kanye: “Musically, he was naive as to what he was doing and couldn’t articulate. But it was all about what he felt. It was almost like a little kid. If we were to record it now, it would sound so different. We went with how we felt and with what we heard in our heads.”

Kanye proudly represented Chicago, and The College Dropout was shaped by the city’s thoughtful rap scene, highlighting local talent like GLC on “Spaceship” and slam poet J Ivy on the triumphant “Never Let Me Down”. But The College Dropout in many ways had a cross-regional appeal, reflecting Kanye’s own geographic journey: Chicago was his home, but he was born in Atlanta, and spent formative years churning out beats in a New Jersey apartment. Kanye strode a metaphorical Mason-Dixon line, effortlessly working with gritty New York legends like Jay-Z and Southern charmers like Ludacris, who shows up on the snappy “Breathe In, Breathe Out”.

There’s even a little West Coast flavour, too: as Kanye readily admits on “Last Call”, his early beats frequently borrow the drum pattern from Dr. Dre’s 1999 track “Xxplosive”. The old-school charm of the chipmunk soul sound drew in multiple demographics too: the smarm and fashion sense appealed to younger listeners, but the deep crate of vintage R&B samples, from Aretha Franklin and Luther Vandross to Chaka Khan, made it safer to bring home to your parents.

In an era when hip-hop was still regarded by many music writers as a special interest, The College Dropout resonated across the critical spectrum. The album topped that year’s Pazz & Jop Poll for The Village Voice, and would be dubbed the best record of 2004 by publications like Rolling Stone, Spin, and Vibe. Some descriptions of Kanye from early in his career – when he was just one rapper among many, and not an industry unto himself – can read a little quaint with hindsight.

He was never the most technically gifted rapper or the most vocally adept singer, but he transformed those weaknesses into strengths, using the audible limits of his voice to foster a sense of vulnerability

Spin’s year-end write-up of The College Dropout described West as the “bling-swinging son of a college professor and Black Panther… preaching fidgety sermons that address life’s soulless grind with soulful sass”. For Rolling Stone, Jon Caramanica wrote that Kanye had “perfected a warm, almost sentimental brand of hip-hop”, but still noted that he “wasn’t quite MC enough to hold down the entire disc” and needed the assistance from more assured lyricists like Talib Kweli and Mos Def.

Kanye himself self-effacingly acknowledged that he wasn’t the most nimble rapper. On the delectably seductive “Slow Jamz”, Kanye’s lover urges him to pick up the pace, and he quips: “I can’t do it that fast, but I know someone who can,” prompting fellow Chicago native Twista to unleash his supersonic flow. That coy acknowledgment of his own deficiencies speaks to Kanye’s approach to collaboration, as he intentionally recruits guests with strengths that fill in for his own weaknesses.

As his own clout as a rapper was still fledgling, Kanye needed credible co-signers, and Jay-Z pulled through on “Never Let Me Down” to offer his blessing. Kanye’s public reputation at this point was largely because of his collaborations with Jay, producing the iconic beats for tracks like “Izzo (H.O.V.A.)” and “Lucifer”. By the time of their 2011 collaboration Watch the Throne, the two mavericks might have been on equal footing in terms of their celebrity, but on “Never Let Me Down”, you can feel Kanye seeking the approval of the man he would refer to as “big brother”.

At the height of Kanye’s critical acclaim, few publications heralded his perceived genius as much as Pitchfork, which awarded a rare perfect 10.0 score to My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy in 2010. The College Dropout earned him the first of a staggering seven Best New Music designations in the publication, but the 8.2 review of the album is actually fairly restrained in its praise. Critic Rob Mitchum pointed out a “bloated tracklist, guest star overload, and lyrical paradoxes”, going so far as to encourage listeners to “take the editing into their own hands” and delete the abundance of skits from their iPods.

Still, in Mitchum’s view, the record’s “flaws tend to only help make Kanye West all the more personable as an artist”, which speaks to the unique connection with audiences Kanye fostered from the jump. He was never the most technically gifted rapper or the most vocally adept singer, but he transformed those weaknesses into strengths, using the audible limits of his voice to foster a sense of vulnerability.

That Kanye was once genuinely relatable makes his current calcification even sadder – the hollow emptiness of his most recent demos just magnifies the warmth of his best work. On “Family Business”, one of the most overtly heartfelt tracks of Kanye’s career, he conjures sentimental memories of childhood days gone by, which is almost what listening to The College Dropout today feels like.

Revisiting the album brings to mind a simpler time, when Kanye was a hungry underdog instead of an embittered billionaire in search of his own private Xanadu – a time when engaging with his work didn’t feel like taking a political stance. Kanye might have bought into the myth of his own genius, but one thing he never pretended to be is perfect: he was telling us about his flaws and failures from the very beginning.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News