Columbine survivors can’t believe that the shootings haven’t stopped 25 years later

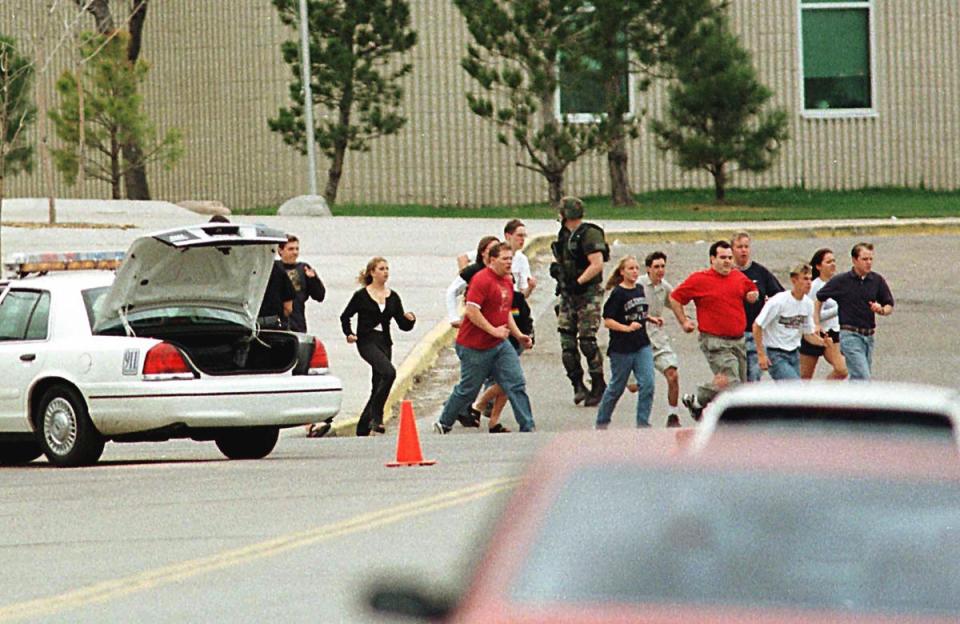

The haunting images have been seared into the minds of generations across the globe since the day footage broke from outside a town in the Colorado foothills that most had never heard of: Littleton.

Students were running for their lives from Columbine High School as gunmen stalked the halls and set off bombs. One desperate teen hung from a window. Nearby homeowners were taking in fleeing children as law enforcement flooded the school, eventually finding the two perpetrators dead of self-inflicted gunshot wounds in the library.

News cameras – and the snowballing behemoth of 24/7 cable – captured almost all of it.

Viewers couldn’t stop watching and then couldn’t forget. There had been school shootings before, but none like this – and none beamed directly into the living rooms of horrified families all over the world. Twelve students and one teacher were dead; 24 others were injured, mowed down in a middle-class high school on an uneventful Tuesday: 20 April 1999. What had happened seemed unthinkable, a tragic and condemnable one-off.

It wasn’t.

Twenty-five years later, Columbine survivors, the relatives of the dead and the wider, still-traumatised local community have watched in horror as the same type of attacks happen over and over and over again. As of April 2024, there have been almost 400 school shootings since that devastating day in 1999.

“A lot of people will say to me, ‘Gee, are you shocked that we’re still having these school shootings?’ And my answer is, unfortunately, no – because it’s happening in our grocery stores, our hospitals, in our shopping malls, in our homes,” says Tom Mauser, whose 15-year-old son, Daniel, was killed at Columbine.

“Why do you think it wouldn’t happen in our schools? They’re a reflection,” he tells The Independent. “Then you have this problem of social media — I think that’s something that’s happening in schools that doesn’t happen in the general population, just such fuel on the fire.”

Mauser, 72, has become an outspoken gun control advocate in the years since his son’s murder. He is speaking on his way home from a trip to Washington DC, where he joined Colorado congressmen, survivors and other advocates in a demand for more gun violence prevention after Rep. Jason Crow introduced a resolution in remembrance of the shooting.

On Friday he’s attending a vigil he helped organise near the Colorado State Capitol. The actual day of the anniversary, he says, is reserved for family.

“The only thing we do is we go to Daniel’s grave, put flowers, and we try to go out and do something that gets our mind off it,” he says.

He and his wife still live in the same house where they raised Daniel, a “straight A student, very shy, very inquisitive” boy who loved to play board games, according to his father.

“You just don’t expect to not have your child with you anymore,” Mauser says. “To me, he’s still 15. I don’t go there, in terms of what he’d be doing today, what he’d be like.”

Hundreds, if not thousands, of their neighbours in Littleton, Jefferson and Arapahoe Counties will be turning out on Saturday for community projects to honour the victims with an annual Day of Service.

Columbine High School remains in the same location. Jefferson County officials quickly dropped a proposal five years ago to raze and rebuild the school itself – an idea posited to deter morbid tourism that instead hit an emotional nerve for too many – but a memorial in an adjacent park opened in 2007.

The surrounding area has changed dramatically in the past quarter-century, expanding from a sleepy suburb surrounded by undeveloped land to a residential sprawl growing endlessly in size and price. The school uses a Littleton postal address but is technically in Jefferson County, a point of contention for more than two decades with officials in Littleton. The well-heeled Main Street USA vibe of a picturesque town full of boutique shops and restaurants is set against the stunning backdrop of the Rockies.

When news teams and cable vans arrived in April 1999, “very few people would have seen these huge uplink trucks before,” Susan Thornton, Littleton’s mayor pro tem at the time, tells The Independent. (Officials were hiring for a city manager in April 1999 and had three finalists; one withdrew after the shooting because his wife deemed Littleton too dangerous, she says – a taste of the city’s inextricable link with the tragedy to endure.)

Not only were locals taken aback by the media onslaught, but they were also irate – and many still are – at incorrect narratives. Journalists mixing up Littleton and Jefferson County, whose school system ecompasses Columbine, was one more minor, irritating example.

Other wrong narratives that have persisted through the years are more dangerous.

“When I go out and talk to people, and I ask point-blank, I say: ‘How many of you feel the motivation for the two killers doing what they did is because they were picked on and bullied?’” Frank DeAngelis, longtime principal of Columbine and the man who helmed the school in April 1999, tells The Independent. “And I’ll tell you, a majority of people raise up their hands.

“Now, I am not saying Columbine was perfect, but what scares me is the fact that there are people saying – there’s kids out there saying – ‘What they did was wrong, but I get picked on, too, and they were sticking up for people like me.’ And that scares me as motivation for these things to be carried out.”

DeAngelis, who recites the name of the 13 dead every morning when he wakes up, was one of the few to view the “basement tapes” made by the two killers which have never been released.

“They did not talk about being bullied,” he says. “They talked about survival of the fittest. They talked about Nazism. They talked about a hitlist. They went on and on and on and on.”

DeAngelis remained principal at Columbine until 2015. He’d initially promised all students enrolled at the high school in April 1999 that he’d see them through graduation before leaving; he later extended that, crediting his priest with telling him he must have been spared for a reason – and was needed to rebuild the community.

“I went back and said, I’m going to stay until every kid who was in elementary school graduated,” he says. “I wanted to be their principal and give them their diploma.”

As DeAngelis continued to lead and support the Columbine community, however, he also became a de facto leader in another unfortunate network: Principals whose schools have endured similar attacks.

For years, as DeAngelis has watched shooting after shooting hit towns across the country, he’s also counselled other school heads in the aftermath.

“Everybody deals with it differently, and not every situation is the same,” he says, noting that he’d already helmed Columbine for years at the time tragedy struck and had an established “support system.”

“I’ve had principals come up and say, ‘Frank, I can no longer do this. It’s affecting me.’ And I say, ‘No, you have to do what you need to do to take care of yourself.’”

He implements his own advice too; DeAngelis has been in counselling since the shooting and emphasises its importance. It taught him to utilise two religious medals around his neck – a crucifix and a miraculous medal of the Virgin Mary – which he touches upon news of the latest shootings. He rattles off the dates of the incidents with barely a thought.

“I remember when I’m sitting at my computer, hearing about Parkland, and I saw those kids running out of the building with their hands up; it really took me back to 1999,” he says. “It wasn’t February 14, 2018. All of a sudden, I grasped the medals around my neck, saying, This is February 14, 2018. This is not 1999. And so that gets me back to where I need to be.”

No one affected by Columbine – and there are far further ripples of victimhood than most people realise – can believe the frequency and severity with which these shootings continue to happen.

Beverly Kingston, now director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at the University of Colorado Boulder, had just been accepted into a PhD programme at the institution when the Columbine attack occurred. She’d already been working in youth violence prevention beforehand and became heavily involved in post-Columbine research upon her arrival in Colorado.

There was “no way” she could have predicted the continued scourge of such attacks, she says – and, 25 years later, the lyrics from U2’s 40 – “How long to sing this song?” – often play in her head when she hears about the latest shootings.

“Sometimes my initial response is anger; sometimes it’s numbness,” she tells The Independent.

She became director of the CU Boulder centre in 2012, the same year as the Sandy Hook massacre. Journalists and others came to her for answers following that elementary school atrocity, which left 20 students and six adults dead. She reached for her copy of a 2001 governmental report commissioned after Columbine by the Clinton administration and Congress as she considered how to respond.

“I just broke down crying, because I couldn’t believe this quote,” she says, again taking the report from her shelf and reading aloud to The Independent from the preface the main conclusion “that as a Nation, we possess knowledge and have translated that knowledge into programs that are unequivocally effective in preventing much serious youth violence.”

Eleven years after that report, she said, she could not believe “that, here we were, that we could allow Sandy Hook to happen.”

Much did, of course, change and prompt new protocols after Columbine; studies have shown that there were missed signs in more than 90% of such shootings, and countless schools across the nation have put in place behaviour threat assessments and reporting systems.

Kingston watched and helped as Colorado, in the immediate years after Columbine, created and implemented Safe2Tell – an anonymous reporting tool that can be used by peers and members of the community.

“The idea is, if you see anything that’s a safety concern, make a report … you can make a tip through the app, you can go online, you can make a call,” she says. “And it has a 24/7 answering point, and it has trained people answering the calls.”

Still, though, she emphasises that more robust uptake of preventative programs supporting people who are “hurting” has yet to occur.

“A lot of the things that also happened after Columbine was a focus on crisis response, security, and that’s not prevention,” she says. “That’s not addressing the root causes of why someone would get a grievance and would be motivated to attack a school. And we’re going to do a lot better as a society when we make a decision … then put resources behind addressing these root causes of violence.

“And when we do that, we’ll not only prevent these shootings, but we’ll also be helping our young people be on a positive trajectory for their lives.”

The years since Columbine have seen the violence come to her own backyard, even closer than Littleton; she was deeply rattled by the 2021 King Soopers supermarket attack in Boulder that left ten dead. The daughter of Tom Mauser’s family friends was also there; traumatised, she was helped by counselling through a group set up by Columbine survivors.

The ripple effects of the violence are endless. DeAngelis talks about everything from survivors’ guilt among teachers who weren’t at Columbine on the day of the shooting to residents around the school who witnessed the carnage. He was brought in to speak after the same King Soopers shooting and noticed the same patterns being replicated.

“There were people that were living in the neighbourhood that weren’t necessarily in the grocery store, but they saw everything that was happening,” he says. “They said, ‘Every time I look out my window, there’s this makeshift memorial with people walking by with flowers … I’m traumatised and I keep reliving that day.’”

Kingston, for her part, sounds both exhausted and exasperated after decades of research into preventative programs proven to help.

“I am just spread so thin, trying to write for grants, trying to talk, influence policy, trying to communicate in a way that gets people’s attention,” she says. “We need some of the best minds from advertising and communication as thought partners … We have yet to implement these things. I mean, it’s unbelievable.

“They’re bipartisan solutions,” she says “They’re not about guns or no guns. They’re about putting infrastructure in place to prevent violence.”

Tom Mauser, for his part, thinks the gun narrative has lost its way.

“I am not anti-gun … I am anti-gun violence,” he says. “Because that’s what this is about. Gun violence. It’s not about confiscation or anything radical like that.”

While he’ll be laying flowers on Daniel’s grave on Saturday, Kingston will be lighting a candle and taking time for reflection. DeAngelis will be back at Columbine, at the gym, honouring one of the most awe-inspiring stories from the tragedy.

As the two shooters stalked the halls 25 years ago, the principal tried to shepherd a group of girls to safety in the gym – only to find the doors locked. He fumbled desperately with his overladen key ring, grabbing one from the 30 or so. As the shots got closer, the key worked – and the girls were saved.

Remembrance, support and prevention has become a mission in the lives of so many – those who remain determined to fight despite the ongoing national scourge.

“I feel like I have to keep going to do the best that I can to get out what we know works,” Kingston tells The Independent. “And I think about the survivors and the suffering that is created by this horrendous violence.

“It feels like I just have to do it. I guess it’s like a calling … that we have to do everything we can.”

And Columbine’s long-time principal, 25 years after the day that forever entered his school’s name into the public lexicon, will recite their names – as he does every single morning.

Cassie Bernall. Steven Curnow. Corey DePooter. Kelly Fleming. Matthew Kechter. Daniel Mauser. Daniel Rohrbough. Dave Sanders. Rachel Scott. Isaiah Shoels. John Tomlin. Lauren Townsend. Kyle Velasquez.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News