The Conservatives are paying the terrible price for Britain’s lockdown amnesia

On Tuesday, the BBC led with a report about personal protective equipment (PPE) worth nearly £1.5 billion going unused. It was, we were told in scandalised tones, rotting away in warehouses.

Opposition parties were invited to comment. Labour primly called the surplus a “staggering waste”. The Lib Dems concurred, promising to “take steps to ensure such a colossal misuse of public funds never happened again”.

But hang on. Didn’t the BBC, along with the opposition parties, spend the lockdown howling about the need for more PPE? Didn’t it tell us that NHS staff were being treated like “cannon fodder”? Didn’t it finish every report with a quotation from some public-sector union to the effect that ministers weren’t doing enough? Wasn’t it running headlines like “Covid PPE: How healthcare workers came to feel ‘expendable’”?

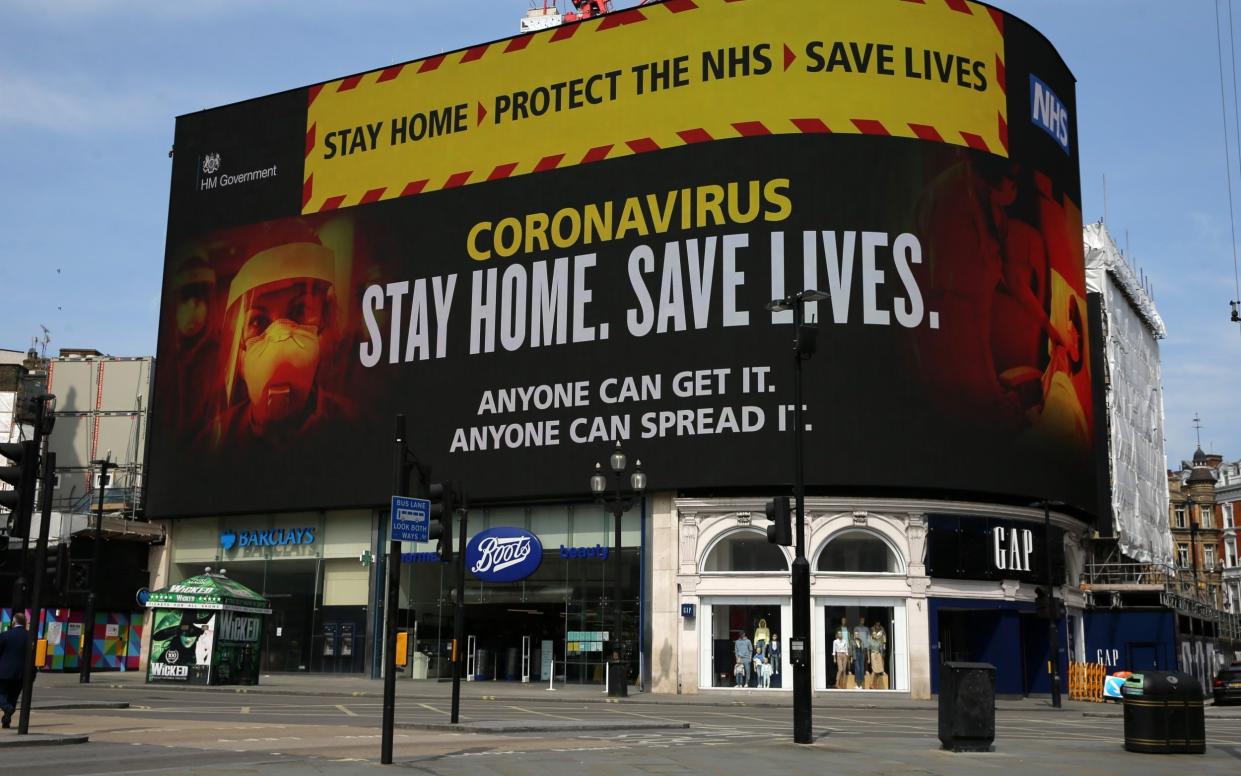

Have we forgotten the demented atmosphere of those days? The pretence that every failure by our procurement-wallahs, whether on PPE, ventilators or testing, was the fault of Boris Johnson? The scramble for kit, which saw reporters despatched to follow a single consignment from Turkey?

I think we have. And I think our amnesia, not just about PPE, but about the lockdown in general, helps explain what is going to happen on Thursday.

We don’t want to think about those phantasmagoric months. We don’t want to remember the enormities, indignities and absurdities we endured. And we certainly don’t want to admit that a policy we ourselves demanded might be at the root of Britain’s problems.

It takes an effort, four years on, to think about what we went through. The taped-off playgrounds. The insolent police. The bankruptcies. The school children who never got their chance to perform their solo, captain their team or say a proper goodbye. The pensioners suffering in solitary confinement. The mounting national debt. The mental health problems hatching in silence. The snitching. The furlough scams. The money-printing. The cancelled weddings. The missed cancer screenings. The police drones pursuing hikers.

God, it was awful. But the worst thing was how popular these restrictions were. Ninety-three per cent of people backed the first lockdown, 85 per cent the second, and a sizeable majority opposed the lifting of restrictions in 2021.

Already those numbers feel ridiculous, don’t they? A lot of people have edited their memories, and now complain about restrictions which, at the time, they wanted to be harsher. Psychologists call it “hindsight bias”.

Having opposed the lockdown from day one, I can’t forget the abuse hurled at the tiny number of sceptics. Those who did the hurling, naturally, find it easier to forget.

Thus, Labour, which fulminated about ministers being “slow on protective equipment,” now has the gall to complain that they bought too much of it.

The Lib Dems, who tore into the Tories for their “failure to ensure adequate supplies of protective equipment reaching the frontline workers”, now chastise them for having over-ordered.

They get away with it because the country as a whole has done the same thing. It is as if we have woken with a terrible hangover, uneasily aware that we behaved foolishly the night before, but unwilling to think about it.

When Rishi Sunak was challenged about NHS waiting lists during the first leaders’ debate, he replied that Britain had been through a pandemic, but that Conservative-run England had shorter waiting times than Labour-run Wales. The audience groaned. If you don’t want to be reminded of the lockdown, any reference to it by a politician comes across as whingeing.

Yet the lockdown cannot be wished away. It squats like a poisonous toad in the middle of every policy discussion. We edge carefully around it. We affect not to see it. Yet there it is, wart-covered and malign, regarding us with cold, protuberant eyes.

Take any issue you like. Education? The number of children “persistently absent” from school has surged since before the lockdown.

The economy? Growth remains sluggish because people haven’t returned to work. It makes life tougher in lots of small ways. Suitcases are slow to reach airport carousels because there are fewer baggage handlers. Trains run less punctually because there are fewer railwaymen. A secondary market has developed in dates for driving tests.

Figures from the ONS suggest that, while the private sector has more or less recovered its pre-lockdown productivity levels, the public sector is years behind. It turns out that government staff who insist on working from home are less efficient. Who’d have thunk it?

What goes for education and public services goes for everything else.

Tax? We dropped the better part of half a trillion pounds on the lockdown.

The NHS? The lockdown caused the waiting lists.

Human rights? There has been no more grievous violation than the confinement of the population to house arrest; yet our activist human rights lawyers cheered it on.

The cost of living? To pay for the lockdown, we printed money like Robert Mugabe on speed. The surge in sickness benefits claims? Once people had become used to… oh, you get the picture.

We talk as if our troubles were wantonly inflicted on us by malicious ministers. But one of the reasons taxes have risen with no commensurate improvement in public services is that we paid people to stay home for the better part of two years, borrowed money to do it, and still don’t want to return to work.

Tolstoy wrote that “everybody thinks of changing humanity, and nobody thinks of changing himself”. He was right. Ask people whether they want change, and every hand in the room will rise. Ask whether they want to change and the arms snap back down. That’s what’s so clever about the slogan “Britain needs Reform”.

Those months of being paid to stay at home altered the relationship between state and citizen. We have become more demanding, less willing to acknowledge trade-offs, readier to blame any annoyance on the supposed meanness of the government.

One politician who recognises the cost of the lockdown is Nigel Farage, who told a crowd in Sunderland on Thursday that the second and third lockdowns had been the worst mistakes made by a British government in peacetime.

It is to his credit that he says so. But what about the first lockdown, which was more severe and more economically damaging? Why does Farage not count it? Is he generously allowing that decisions made during those heated weeks necessarily look different in retrospect?

Or is it that he himself wanted the first lockdown? Our memory-holing of the whole episode means that we rarely recall Farage calling the original strategy of controlled spread “immoral” and demanding that Tony Blair lead a vaccine task force. We forget the sight of him, in a plum jumper and mustard cords, banging his saucepan for the NHS.

Not that I blame him. Most of the country followed the same trajectory, first demanding a crackdown and then moaning about its effects. Farage came around far quicker than most and was indeed a critic of the later lockdowns. But governments, unlike commentators, are not permitted such inconsistencies.

The paradox of the current election is that both Johnson and Sunak were more sceptical of the lockdown than most of those who now blame them for it. Recall that Keir Starmer opposed the loosening of restrictions, and even wanted them reimposed at the end of 2021.

Except that no one does recall it. Our anger, whether directly over the lockdown or, more commonly, indirectly over its costs, is aimed at the politicians who held out against pressure to go even further. Funny old world.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News