'I was considered one of Britain's most dangerous prisoners - after 22 years in the toughest jails this is my story'

Once considered so dangerous he was isolated for seven years in a system described as 'torture' by a UN human rights expert, Dwaine Patterson's story begins on an estate in Wandsworth, where a traumatic beating made him vow to never let it happen again.

Here Patterson says he got 'an appetite for blood' and ascended through criminality, cut off another child's thumb with a meat cleaver then, as a young man, shot two men in a robbery. The first crime landed him in a youth jail for five years, the second earned him a two-strike life sentence - an automatic jail term that his since been abolished.

Persistent fighting saw Patterson, now 44, moved to the toughest prisons, then, just as he was turning a corner, allegations of a throat slashing and Islamic extremism, for which he was never convicted, were followed by seven years in isolation. A sentence that began with a minimum of seven years became 22, and accusations of radicalism put him on restrictions that only ended four months ago. Now he is free, he wants people to hear his story.

MyLondon was unable to verify some of the claims made by Patterson in this piece. We put the allegations to the Ministry of Justice, and a Prison Service spokesperson told us: “These claims are historic and unverifiable."

‘I told my mother it would never happen to me again’

On the Patmore Estate, you were either from Deeley Road, Kerry Gardens, Thessaly, or Corunna. But when eight-year-old Patterson arrived at Patmore, he came from none of them. An intergenerational rivalry with his birthplace, Clapham Junction, immediately made him an outsider on his own street.

Back then, he says the Patmore youngsters mindlessly followed history without asking ‘Why?’. “When you’re born,” he tells me, “You’re born into someone else’s story, until you get one of your own.”

Patterson's story began here in the late 1980s with nine sisters and five brothers, a rebellious Rastafarian dad in an otherwise Christian family, and a loving mother. It was a time when ‘Blacks and Irish’ all became friends, when his father’s dreadlocks defied the Christian values of his grandparents, and you had Rastas living upstairs with Hells Angels downstairs.

Unlike some young boys who are led astray into gangs and youth violence, Patterson says he had strong male role models, including a step-dad who taught him the value of hard work. “I can’t say I had a disruptive childhood – I had a good one,” Patterson admits, fondly recalling the Caribbean community spirit and games of dominoes on the kitchen table.

But while life was good at home, the skinny little boy from Clapham Junction took different routes to avoid the kids waiting for him any time his mum sent him to the shops. Then one day, when he was just 10, Patterson was collared and they demanded his 8-ball jacket, an iconic bit of 1990s hip-hop wear.

Surrounded by muggers, most people would just hand over the jacket. Not Patterson though. “I said no,” he said, as he claims he was kicked and punched, while his cries for help were ignored by adults strolling past.

“At the time I never understood it, as adults were protectors," he explained. "I saw people who were supposed to resolve situations were walking away. When my mum took me to the hospital, I told my mother it would never happen to me again.”

It was this sort of injustice, Patterson claims he would constantly fight against for more than two decades. But years before he would find himself considered one of the most dangerous prisoners in Britain, 10-year-old Patterson had to establish himself on the estate by challenging another child for supremacy.

“I think it was just anger and rage,” Patterson said, vaguely recalling how he injured the other child. “I developed an appetite for blood. I realised this is the currency people are living by.”

Armed with a dangerous new mindset, Patterson became the leader of his own little team, going to neighbouring estates for punch-ups, becoming desensitised to the same violence that had damaged him so badly before.

While he was marking himself out from his law-abiding siblings, the other boys from their broken homes were looking for acceptance, and something to eat. Before, he yearned for their freedom. Now, he looks back at those boys as the product of dysfunction.

‘There was one kid everyone surrounded’

It was in this period that Patterson’s behaviour started to count against him in a big way. Describing himself as ‘highly intelligent’, Patterson says his biggest issue was ‘getting involved in things that did not concern me’ and fighting anyone who tried to take advantage of someone else.

Though he passed the Eleven-Plus exam for top private schools Emanuel and Westminster, Patterson's behavioural record at primary school let him down, and the private schools weren’t prepared to risk exposing him to other pupils.

Instead he went to a local comprehensive and was kicked out within two years. After sticking his foot out to trip an older kid down the stairs, he slipped out of school over a fence and called for backup.

As Patterson recalls, some associates ‘did the job’, but blame for the brawl fell squarely at his feet and he was sent to an Individual Tuition centre (IT), known now as a Pupil Referral Unit.

It was Patterson's first taste of an institution, but he says the adults there ‘did not really care’ and he learned nothing unless he was taught it at home. By 1992, he’d been kicked out of three IT centres, but his friend group on Patmore was growing and the older boys were starting to make introductions.

“There was one kid everyone surrounded,” Patterson remembered. “I used to observe this and think ‘I would like that’. Everyone seemed to hang on the one word of this kid.”

That kid, it turned out, was a member of his extended family, and it was his introduction to him that started his path of criminality. Soon he was ‘snatching from tills’ and walking out of shops in two pairs of trousers, wanting ‘to be part of what they were part of’.

But petty crime turned violent when he sliced the thumb off another 13-year-old. Patterson said he harboured a dislike for the boy, running into him on the estate and feeling outnumbered, then asking him for a cigarette and money to ‘stir the pot’.

Once the pot was stirred, Patterson pulled out a meat cleaver - so sharp that it shredded the inside of his jacket - then took the boy’s thumb off. “You understand what you’re doing as wrong, but you do not understand the magnitude,” he said, reflecting on the crime that had him removed from his family. Patterson is careful when he recalls this incident, and says he wants to spare the victim the grisliest details.

Patterson was too young for prison, and too young even for Feltham Young Offenders Institution (YOI), so as he waited for his court date he passed between secure units for children in Mitcham, Shepherd’s Bush, Crystal Palace, and Bristol. It was the first time Patterson was ‘essentially locked up’, and this is where he claims the pattern of abuse, fights, and transfers, that marked his prison career, would begin.

“Some of the staff were very sadistic,” he alleged. “They would physically abuse you. They would punch you in the stomach.” Continuing the allegations - which the prison service has said were historic and unverifiable - he said: “Imagine grown men bending your arms behind your back, suffocating you. If you showed any emotion they would take the mickey out of you. It was quite horrific.

“You are developing still, and you start to dislike the system. They justify it as ‘you’re a criminal’. I totally understand that I have committed a crime, but how can you justify treating a child in that way? People do not care. They do not want to hear the sob story, they want to throw away the key.”

After the meat cleaver attack, Patterson waited two years to appear at Inner London Crown Court, where he was convicted of GBH and jailed for five years. During this sentence he also picked up another three-and-a-half year concurrent jail term for an attempted robbery he had committed while he absconded ahead of the GBH trial.

“What I realised was punch first, ask questions later,” he said, claiming older bullies would test his nerve by asking for things they had no interest in giving back. “If you did not respond to that, they would see you as weak.”

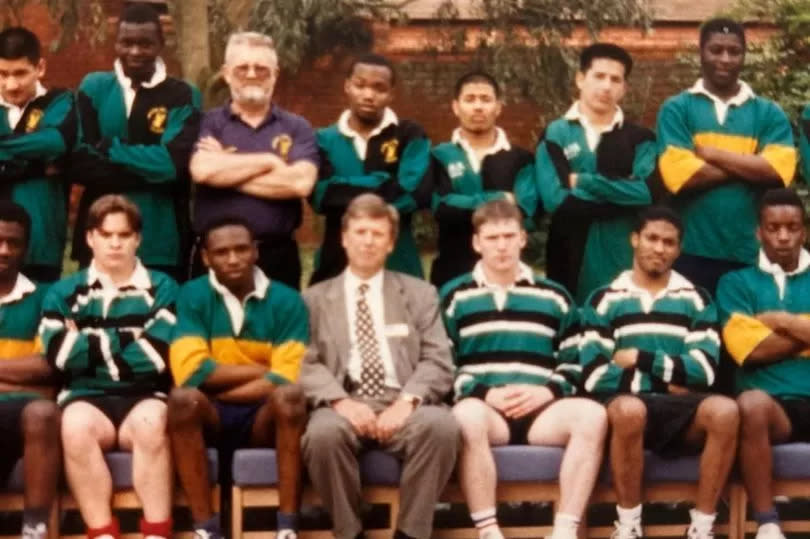

But Patterson rose to the challenge. He started lifting weights and played in a rugby team that made headlines when they stuck it to private school boys at national 7s tournaments. Led by an inspirational prison officer called John Gunning, you can still read match reports about the time Feltham Black Sheep tested Eton and beat Sutton Valance.

For the first time in our conversation there is a spark in Patteron’s eyes as he remembers studying rugby games from Australia, the future home secretary Jack Straw coming to meet him, and reaching the finals at Lytchett Minster. But the jump to Middlesex 7s, where young lags were up against posh boys with years of experience, was one step too far, and in the end, Patterson went back to what he knew best - Boxing.

‘I did something I’m totally ashamed of’

After leaving Feltham YOI in August 1998, Patterson struggled to adjust to adulthood, no longer receiving the support he had from his parents as a child. "The thing that was demoralising was how unforgiving society can become and the lack of opportunities that were frustrating me," Patterson said, lamenting how he 'just gave up'.

It wasn't long before Patterson found himself back in prison for a bank robbery and double shooting. The bank was a Barclays in Clapham Junction where Patterson says he 'obtained' some money. Back then he says there was a code not to hurt civilians, but pressed on the impact of his crime he recognises there’s such a thing as mental trauma too.

"We would just look at the physical aspect of things, but the psychological aspect is very frightening," Patterson said.

While police were building the case for the bank robbery, Patterson claims one of his family members was jailed for five years [MyLondon has been unable to verify this). Ironically, another family member, the one he looked up to and ‘everyone surrounded’, had already decided a life of crime was not for him.

Patterson carried on though, and one day he got a tip off about a van involved in drugs. Using that cold and methodical verb again, Patterson said: “So we went to obtain. We went into the premises and I done something I’m totally ashamed of.”

Patterson spoke of his mentality back then: “If I show you a gun, I use it.” Now he just thinks that was ‘silly Neanderthal behaviour’. But that night, totally unaware his accomplice was actually a police informant, he pulled out a 357 Magnum and fired three shots at two men when they refused to hand over an envelope full of cash.

“I thought it was justified because I saw them as criminals,” he said, a sentiment noted by a probation officer at the time. In a prison service document, seen by MyLondon, the author wrote: "His allegation the victims were not law-abiding themselves, and involved in criminality, in his view, renders them unworthy of sympathy."

As well as ‘no civilians’, and ‘using the gun when you show it’, Patterson had another ‘demonic rule’: 'Only shoot people you can touch'. “My intention was not to miss,” he said, recalling how a man was left fighting for his life after taking bullets to his chest and stomach, while the other man was struck in the leg. Luckily neither man was killed.

‘Suppression, oppression, depression’

So, at 20-years-old, Patterson was on the run. Already hunting him for a string of shootings, and with the help of the informant, police officers had been waiting at the scene. But Patterson managed to escape.

A few days later though, he handed himself in. Patterson says the informant had used the name of a woman to hire a car. Patterson claims the woman was now being threatened with the removal of her child if she didn’t give up a name.

Looking back at the incident that landed him in jail for over two decades, Patterson claims he was betrayed, but it’s not something he’s still upset about. For him, betrayal was like getting shot: an occupational hazard.

“Let’s be honest. The lives I have ruined myself. That’s what upsets me the most,” Patterson said. “I almost killed men for what reason? Because they had something that I wanted. How is that justified?... It was only a matter of time before I ended up dead or in prison. God gave me the latter: Incarceration.”

Unlike his first time in court, when Patterson maintained a code of silence, this time he pleaded guilty to the armed robbery, two attempted murders, and firearm possession. He was jailed for seven years minimum at the Old Bailey, but the judge also imposed a Section 2 discretionary life sentence – also known as a ‘two strike lifer’.

Introduced in 1997, this type of sentence could be imposed if a defendant had a previous schedule one offence (like GBH), no matter how long ago. They were outlawed in 2003 and replaced with the Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentence, which itself was abolished in 2012.

His schedule one offence came when he was a child, but it still counted against him. It meant he would spend the next 22 years in prison. Those first eight years, Patterson says, were ‘pandemonium’.

“When I was on remand, I must have visited every London prison about two to three times. No place wanted me because of my behaviour.," he said. Now he just cringes at the memory. “Looking back, it’s quite embarrassing," he admits.

Patterson returned to Feltham YOI, where he alleges the prison officers fought the inmates. Here, Patterson insists, he only fought people who took advantage of others. “I was a violent prisoner, there’s no denying that,” he said, "but I still think the system was totally unacceptable. What is an excuse for a person with a duty of care to behave in that fashion?”. The prison service says these claims are historic and unverifiable.

Patterson also claims there was a constant threat of ‘liquid cosh’, prison slang for a cocktail of psychotropic drugs used to pacify difficult inmates. He heard unverified rumours the drugs could be used to ‘develop’ mental health issues that weren’t there, which would then become the basis for a transfer to a high-security psychiatric hospital like Broadmoor.

Through his time in the system, he claims the system of violence adapted to modern sensibilities, and by the time he was freed, bureaucracy was the biggest tool of oppression. “They became pen pushers and destroyed you in that way," he alleged in a claim MyLondon has not been able to verify.

Five years into his sentence, the prisons in London were 'fed up' with Patterson’s behaviour and he was moved into the dispersal system. This was a system of five Category A prisons set up in the wake of high-profile escapes in the late 1960s. The original plan was to house all the problem prisoners in an Alcatraz-style prison on the Isle of Wight, but the government decided it would be better to split everyone up. Hence ‘dispersal’.

In 2005 Patterson ended up at HMP Whitemoor in Cambridgeshire, a move that felt like playing at the national standard rugby tournament. “It was a whole different ball game,” Patterson said, recalling how some of the men there would never be released. It meant violence was now even cheaper.

“They would kill you for a slice of bread,” Patterson alleged, claiming even the prison officers were too scared to go on the prison landing. But even surrounded by the toughest men in the criminal justice system, Patterson maintained his reputation for violence and had to be transferred at least six more times.

At the same time, Patterson was getting closer to his faith, having already converted to Islam at the age of 16. It should have been a positive, but he claims this also made him a target in the post 9/11 world, with growing fears about Islamist radicalisation after the London bombings.

The attack on London was 'barbaric' and 'an act of evil', Patterson said, but he also accused officials of 'scaremongering'. "The backlash against people in the prison system was crazy. It gave people with racist views carte blanche to do what they want," he claimed. It was against this backdrop, that a series of events would land Patterson inside an isolation unit for nearly seven years.

‘Something is going to go down’

At Whitemoor in 2010, Patterson claims he intervened when he saw prison officers restraining another inmate - something he describes as ‘a George Floyd moment’. He maintains it was his ‘civic duty’ to stop the restraint, but he was accused of assaulting six officers, moved to segregation, and hit with criminal charges.

But Patterson was moved back into the wings when he would normally have expected to stay in ‘seg’. “Everyone said it was suspicious. Everyone said ‘Be careful, they are trying to set you up, something is going to go down,’" Patterson said.

Two weeks later, Patterson was standing next to the Imam in the prison mosque when he says a man’s throat was cut in front of around 100 people. Almost immediately Patterson was dragged out and accused of carrying out the attack, even though he maintains he was nowhere near the victim. The prison service told MyLondon these claims were historic and unverifiable.

As well as the slashing, he was accused of leading a ‘Muslim boy gang’, controlling others and forcing them to convert to Islam. Patterson has always denied this. Dismissing the ‘weirdos’ who give people like him a bad name, Patterson said: “Those people do not even think I’m a proper Muslim. They were very weird, in their own corner blaming the whole world.”

It was at this point he was referred to the Close Supervision Centre (CSC), an isolated unit, with extremely limited outside contact and recreation, first established in 1998 for the most violent and disruptive prisoners. The former UN special rapporteur on torturer, Nils Melzer, has said the CSC regime may amount to torture.

Stuck in the most confined unit, with two criminal cases pending against him, Patterson says his cell could only be unlocked by a seven-man squad in riot gear plus a dog handler. Later he was moved to another CSC at HMP Woodhill where he was managed by a Tornado Squad – which he says was 'like the SAS of prison officers'.

Patterson says that here officers could use tear gas and rubber bullets, and he was not allowed to put anything in his cell. Unwashed in dirty clothes two sizes too small, he claims officers tried to break his confidence. “It’s to play with your mind, you feel insecure, you feel naked,” he said.

Here Patterson also alleges there was an officer who asked him what he thought about suicide bombings, suggesting he might be a terrorist. Patterson still remembers feeling confused by the questions, having been imprisoned for something completely different.

The questions persisted though, and Patterson claims the officer came out with racist and Islamophobic views; he allegedly told him to ‘go back to his own country’ and said 'white women who sleep with Black men should be killed'. The prison service told MyLondon these claims were historic and unverifiable.

Patterson, who says he felt isolated and frustrated, eventually lashed out during a six-man unlock, something he admits and was later convicted of. But the cases against him for his restraint intervention and the accusation of attempted murder he refused to plead guilty to.

Patterson claims another man handed himself in for the throat slashing, the Imam corroborated his position in the room and says his legal team had 109 witnesses prepared to say he did not do it. But, he says, prosecutors still pressed on with the case.

In the end, it took three trials over three years for Patterson to be cleared of the most serious charges. He was convicted of assault and ABH during the six-man unlock, but was acquitted of attempted murder and for assaulting the officers who were restraining another inmate.

Patterson claims the prosecution showed he was being stigmatised as a Muslim, just at a time when he was starting to make progress. A prison service document from the time said prison staff observed Patterson had 'matured in the last year', but the board still recommended isolation due to 'numerous adjudications which included assaults on a prison officer'.

Patterson said that the presence of 'EDL and neo-Nazi types', who he claims were able to smuggle weapons into the prison with the help of sympathetic officers, were more of a concern to him. Violent racists were a real threat, but Patterson says they often got disarmed and stabbed themselves.

He also remembers one particular incident when he alleges a man was made to parade naked in front of prison officers after kicking off about their refusal to give him a phone call after the death of his mum. The prison service told MyLondon this incident was historic and unverifiable.

“He was a racist, so why would we feel sorry for him?" Patterson added. "But I remember thinking ‘Enough is enough’. I think that’s a memory that sticks with me, how they beat that prisoner with no compassion.”

From 2010 to December 2016, Patterson had no neighbours, was only allowed out for one hour a day, and visits were limited. Prison service documents show successive justice ministers, Kenneth Clarke and Chris Grayling, agreed with the parole board's view that Patterson was too dangerous to live in the prison population.

In 2014, Patterson's fifth parole board review said his record was 'extremely serious' set against 'a background of violence from a young age' and he had 'not addressed in any depth' his use of violence. But, the report writer also recognised the effect of isolation, stating 'It may be of course that this is due to his continued placement, as a result of behaviour, on the CSC'.

The report concluded he was 'highly unlikely' to return to open conditions as he 'has not yet addressed the major risk factor of violence'. With prison service officials repeatedly concluding Patterson was too dangerous, his stay in the CSC would drag on for over two more years.

'God, family, patience, and discipline', Patterson says, kept him going during his seven years in the CSC. He used the time to read classics like Les Miserables, a fictional story about a man who serves 19 years for stealing a loaf of bread, and a book about the Soledad Brothers, three men accused of murdering a prison guard at a Californian prison in 1970.

Patterson also learned from more hardened inmates like Robbo, who had been there 20 years and told him to watch one cartoon a week 'to soften the heart’. Consuming documentaries and news also kept Patterson in touch with the world outside.

After he eventually left the CSC, it didn’t matter that Patterson was found not guilty of attempted murder at his trial. His fate still lay with the parole board, whose decision it was to assess if Patterson was safe enough for society. Sixteen years after the double shooting, he was moved down a level into HMP Full Sutton in Yorkshire, a small step towards freedom.

While it was no CSC, Full Sutton was still part of the dispersal system. But unlike his tumultuous time in Whitemoor, Patterson was allegedly told by the governor to come to them before taking any issues into his own hands.

After another year, Patterson moved down again to HMP Dovegate in Staffordshire, a Cat B, where he says he was given responsibilities as a wing representative. Another 18 months went by and he was moved to a London Pathway at HMP Brixton, a Cat C resettlement prison that is just short of being open.

This is where his story could easily have ended, but here Patterson claims he was ‘smeared’. He alleges he was accused of giving a radical sermon to other inmates and his cell was searched for a phone every week. In 22 years, Patterson says a phone was never found in his cell, and he has always denied trying to radicalise other inmates. This claim has not been verified.

"It was harassment on the highest level," Patterson claimed. "If someone sent me a book it would take six weeks for me to obtain it because they had special people reading my books. They handed me down books and said it was all fine. But then when I had my parole hearing they said I had books of an extremist nature. But the books weren't even on the banned list."

But there was more to come. When Patterson was moved down to Standford Hill, a Cat D open prison in Kent, he got what he calls the biggest shock of his life. He said: “One day I was asked to attend a probation appointment. I saw this young lady come up on the screen. She said ‘I would like to introduce myself, I’m from national security supervision. I will now be taking over your case’.”

For the next three years, even after his release from the open prison in November 2022, he says he was assigned an SO17 counter terror officer, put on a GPS tag, and had to report back to his approved premises every two hours.

Patterson claims he was excluded from his own parole hearing due to ‘national security reasons’ and his lawyer was not allowed to say what happened. The only reason he can explain the reasons for the national security supervision is because he saw a partially unredacted document, which included a litany of allegations against him.

Patterson alleges: “They said I had underground cells waiting to commit an atrocity. They said I had international links. They said I have connections with the Taliban.”

"I said to them it was the equivalent of calling someone a paedophile. How upset would you feel? You would fight every ounce to clear your name. They were calling me a terrorist. A murderer of kids. They were saying I was inspiring those people. It could not sit well with me, it never sat well with me." This claim has not been verified.

Patterson alleges the accusations stretched to his family too. After an uncle sent him a card saying ‘keep your chin up’, Patterson claims his supervisor told him that was a signal for him to commit an atrocity. The ‘final insult’, he alleged, was the alleged accusation he radicalised his own mother.

Our London Court & Crime newsletter brings you the latest major court updates and breaking news straight to your inbox. You can sign up HERE.

MyLondon has seen parole board document that show Patterson was released on life license in 2022 under the National Security Division (NSD) due to 'concerns about potential extremist ideology' with a 'range of conditions linked to extremism to manage risk'.

The conditions listed in the document included not to attend meetings, other than those purely for worship, without permission from the supervising officer; not having material that promotes religious violence; not to contact those with convictions for extremist offences; not to give sermons without approval; not to promote extremist grooming; and only to attend agreed places of worship.

But, Patterson says, when a trained Imam was sent to assess him, he concluded he was not a threat. Patterson also claims the Imam was asked to double-check after failing to identify any concerns. The prison service told MyLondon these allegations are historic and unverifiable.

Patterson's national security supervision ended in November 2023, when, according to the document seen by MyLondon, he had made enough 'progress' to revoke the license conditions and move him to regular supervision under the probation service. While the facts around the allegations of radicalisation remain sparse, Patterson believes it all ties back to the man whose throat was cut.

“They can watch me all they want, I don’t care. I’m not doing nothing,” Patterson says as our conversation draws to a close. It’s been four hours and we've barely spoken about how much the world has changed since his time inside.

After two decades to think about what he will do with freedom, Patterson is busy. He has plans to run as a Lib Dem councillor in 2026, and he’s got a clothing brand called Primrose Hill. He’s also speaking on a podcast called Uncles and doing outreach with young people on street corners.

Perhaps most importantly, Patterson is using his long and painful experience to work as a prisoner mentor with St Giles Trust. When we sit down, he's just been at HMP Isis in Thamesmead and he's still trying to make sense of the visit. He's upbeat at the opportunity to impart his wisdom, but he can't help sounding forlorn about the reality younger prisoners face.

"Just seeing the young men knowing they are going to serve the time I have served," Patterson tells me. Then he trails off and begins his story about life on Patmore Estate in the late 1980s.

Got a story or a court case we should cover? Please email callum.cuddeford@reachplc.com or WhatsApp 07580255582

Yahoo News

Yahoo News