Who’s who at Cop28: the leaders with the world’s future in their hands

Cop28 officially opens on 30 November in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, and the conference is scheduled to end on 14 December, although is likely to run later. World leaders will attend the world climate action summit segment on 1 and 2 December and after they depart the crunch negotiations will be done by their representatives, environment ministers or other high-ranking officials.

Sultan Al Jaber, Cop28 president

Sultan Al Jaber, the president-designate of Cop28, is minister for advanced technology in the government of the UAE, and the co-founder in 2006 of its government-backed renewable energy company, Masdar. Much more significantly, Al Jaber is also the head of the UAE’s national oil company, Adnoc.

This is the first time the chief executive of any company has acted as Cop president – the job usually goes to career cabinet-rank politicians such as the foreign minister. To have the head of an oil company take on the role is not only unprecedented, but for many campaigners – and some other countries – a travesty.

Al Jaber has taken the criticism in his stride. He argues that he can bring a “business mindset” to the talks, and who better to bring fossil fuel interests to the table than someone who speaks their language and knows their business intimately?

Contradictions abound. He has said “the phase-down of fossil fuels is inevitable and necessary”, but Adnoc is still planning a massive expansion of capacity. He will hold a special summit segment on cutting methane, but the Guardian has discovered that Adnoc is flaring methane – contrary to its own claims. Al Jaber hopes to bring together fossil fuel companies into a “decarbonisation accelerator”, but their main goal may be to cut their own emissions, not sell less oil and gas.

The UAE is closely allied with Saudi Arabia – one of the most obstructive nations in 30 years of these talks – if Al Jaber can bring about a change of tone from his Gulf state allies, that could at least be a welcome sign.

António Guterres, UN secretary general

The UN secretary general is probably the most outspoken senior figure on the world stage on the climate crisis. He has talked of humanity committing “collective suicide” and targeted fossil fuel companies who “have humanity by the throat”. This year, amid rapidly rising temperatures, he said: “The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.”

Guterres will champion developing nations at Cop28, encouraging and berating rich countries into providing more support. He is likely to be equally outspoken to leaders of countries with high emissions and inadequate reduction plans, and most of all to the fossil fuel executives who are expected to turn up in large numbers.

Simon Stiell, Grenada’s minister for climate resilience

This will be Stiell’s second conference of the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as executive secretary of the treaty – the official title of the UN’s top climate official. As the former environment minister for the island nation of Grenada, he has long experience of Cops so knows the negotiations inside out. His job will be to work closely with the UAE presidency, acting as an honest broker to all 198 parties, and guiding an agreement through the complexities of the UNFCCC process.

Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados

The prime minister of Barbados, under whom the country removed the British crown as head of state to become a fully fledged republic, has been an electrifying presence at recent Cops and her missions to force the restructuring of international financial institutions has already borne fruit, with a new World Bank president and promises of reform.

Mottley wants to go much further and secure the flow of trillions of dollars of investment each year to the developing world, to transform the global economy and provide protection for those most at risk of climate disaster. She has forged close ties with the French president, Emmanuel Macron, who held a climate finance summit in June, and her Bridgetown agenda is now widely accepted as a potential blueprint for future action.

Ajay Banga, World Bank president

This will be the first Cop for Banga, who took over as president of the World Bank this year after the resignation of David Malpass, a Trump appointee who was forced to resign after a series of gaffes appeared to reveal a degree of climate denial. Banga faces a difficult task: Mottley, the former US president Al Gore, and a substantial number of developed and developing countries want serious reform of the bank, which they say has failed to take the steps necessary to lead the world out of the climate crisis.

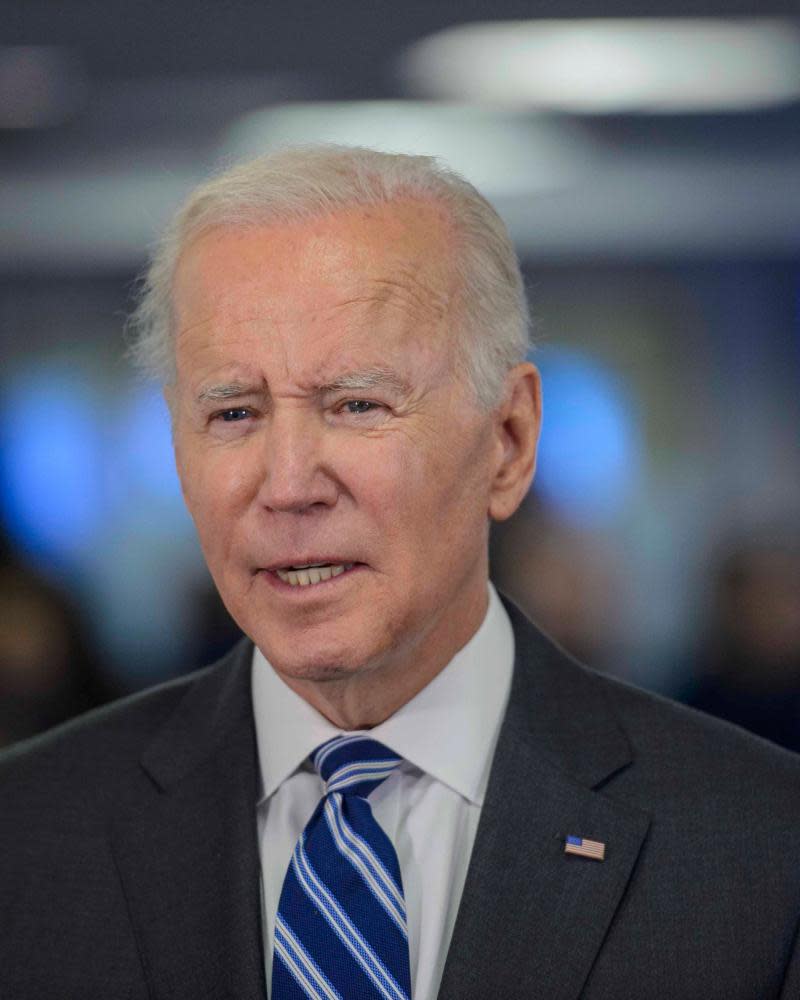

Joe Biden, US president

It is unlikely that Biden will attend Cop this year, though his appearance last year was greeted with enthusiasm. The Inflation Reduction Act is now beginning to have an impact on the US and the global economy and it has spurred not only investment in the US but reactive models from the EU, the UK and other developed countries. But Biden has also presided over a massive expansion of oil and gas drilling across the US, and is so hamstrung by a Republican House there seems small chance of the increase in climate finance that developing countries are – quite reasonably – clamouring for from the world’s biggest historical emitter.

John Kerry, US special presidential envoy for climate

As secretary of state, Kerry signed the Paris climate agreement for the US, with his granddaughter on his lap. The former US senator and presidential candidate, now Biden’s special envoy on climate, is one of the biggest beasts at Cops, and gets on well at a personal level with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua, with whom he had a cordial meeting earlier this month resulting in a declaration that the world’s two biggest emitters would cooperate further on the climate. Kerry will have some tough questions to answer from developing countries, however: the US has consistently come up short in climate finance and is now the world’s biggest exporter of oil and gas, despite Biden’s publicly green stance and the achievements of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Wopke Hoekstra, EU climate commissioner

When the former Dutch foreign minister, Frans Timmermans, resigned this summer to fight in the Dutch general election, he left an outsize vacancy. Timmermans, the vice-president of the European Commission, was one of the most energetic figures at the Cop talks, squeezing sometimes squabbling EU member states into unity – the EU negotiates as a bloc at Cops – and invoking drama at tense moments. His place is taken by Hoekstra, still largely an unknown entity, whose job will be to try to hold the course on the EU green deal and climate action against attacks from the resurgent populist far right.

Xie Zhenhua, China’s climate spokesperson

The veteran Chinese climate envoy has been a key figure at Cops for more than a decade, and he enjoys a cordial relationship with Kerry. China, the world’s biggest emitter, is pivotal at Cop talks, but its national plans on emissions – called nationally determined contributions, under the Paris agreement – have been criticised for not going far enough. However, there are encouraging signs in the form of a surge in renewable energy capacity that could soon herald a peaking of emissions – if China’s strong coal interests do not stage a successful fightback.

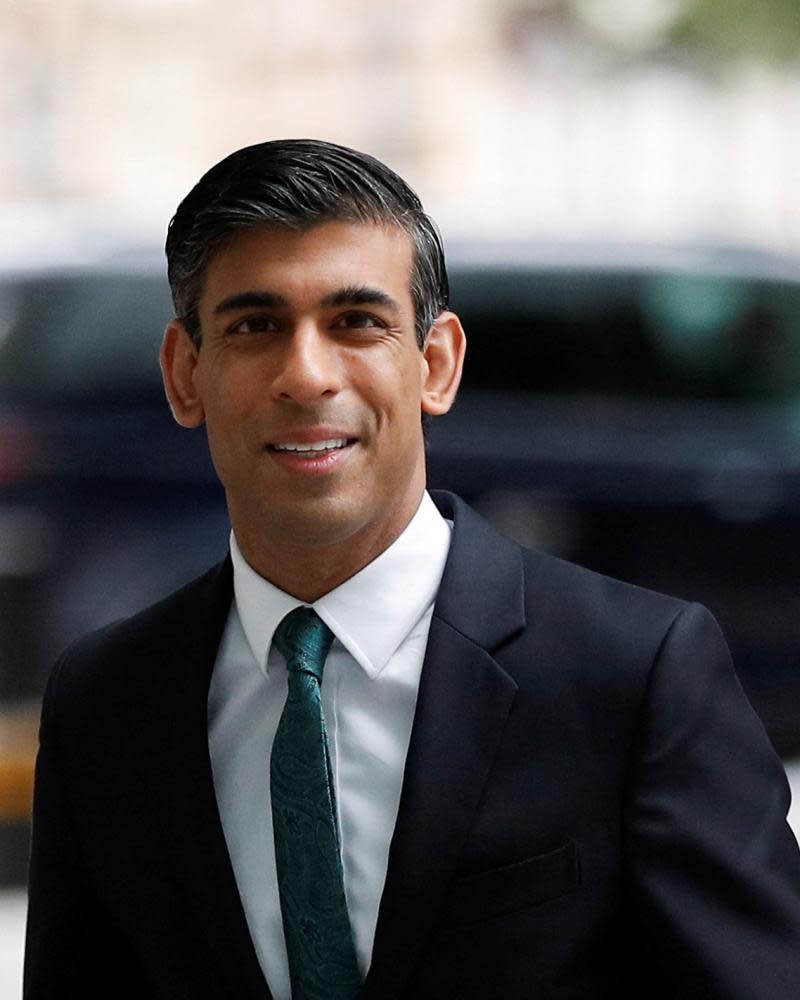

Rishi Sunak, UK prime minister

Sunak snubbed the UN general assembly this year where an invitation-only meeting of world leaders was convened by Guterres. He will attend Cop28, but in the shadow of recent U-turns on key climate policies, which the government’s climate watchdog said would damage the UK’s ability to meet its legally binding net zero targets, and of his vows to “max out” the North Sea.

These policies are unlikely to endear him to world leaders and have provoked outrage, even from members of his own party. He will face charges of recidivism and betrayal. A roll call of UK heavyweights have poured criticism on him: Lord Stern, the economist, excoriated Sunak’s record of “backsliding” on the climate recently in the House of Lords; Lord Deben, the former Tory environment secretary, has decried his hypocrisy; and Lord Turner, the former chief of the committee on climate change, said the UK’s green light to a new coalmine was encouraging coal proponents in other countries.

Perhaps more concerning for Sunak, opinion polls appear to show that his anti-green rhetoric has turned off even more voters.

King Charles III

As Prince of Wales, Charles made his first public speech on the environment in 1970 and has been a staunch advocate of conservation and other environmental causes since, assembling groups of businesses to commit to emissions targets. Ahead of Cop26, he launched Terra Carta, asking organisations to sign up to environmental principles, and has hosted business leaders, dignitaries and diplomats, including Kerry, with whom he gets on well. He has attended previous Cops, including the Paris summit of 2015 and Cop26. The ban on his appearing at last year’s Cop27, initiated by Liz Truss and reinforced by Rishi Sunak, came as a bitter blow to many who applaud his advocacy and convening power. The UAE’s ruling family, which has close ties to the UK’s monarchy, was keen to have Charles deliver a keynote speech this year and he will relish the opportunity.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News