Coronavirus and airborne transmission: scientists warn Australia to be on guard

A collective of Australian researchers across scientific disciplines will call on the government to introduce minimum requirements for building ventilation and to consider caps on the numbers of people sharing indoor spaces as researchers question role of airborne transmission in the Covid-19 pandemic.

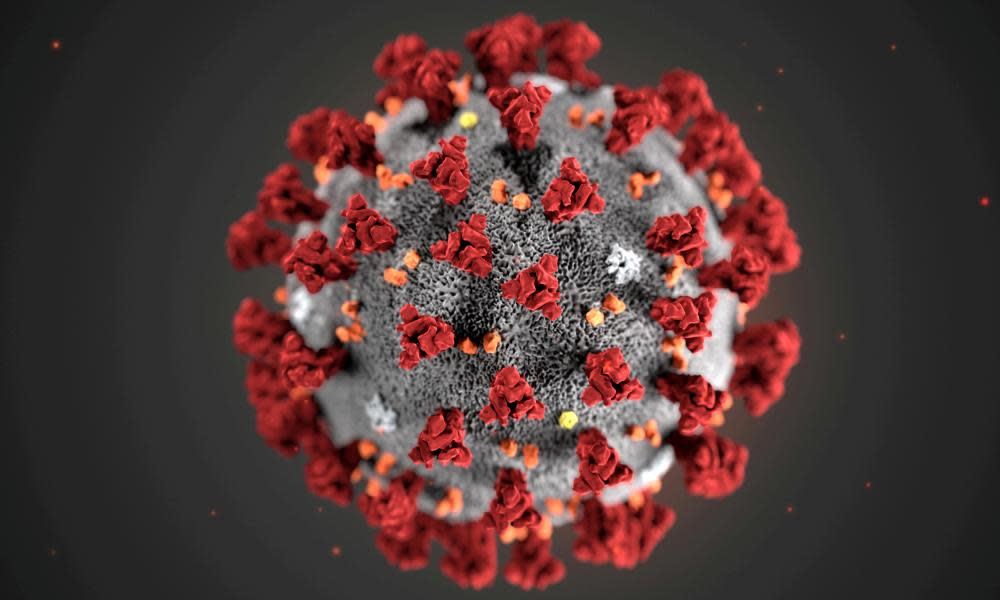

Coughing, sneezing and wheezing generates particles of various sizes. Droplets are defined as large, wet particles generally greater than 20 micrometers in size that fall close to the person. These contaminate surface areas or people nearby. Aerosol spread, also known as airborne spread, comes from dried particles – referred to as “droplet nuclei” – that can disperse over long distances and remain suspended in the air.

Related: Trans-Tasman travel ‘bubble’ to allow flights as soon as lockdowns ease, Morrison and Ardern agree

According to the World Health Organization, Covid-19 is primarily transmitted between people through large respiratory droplets that settle on surface areas and spread through human contact. In an analysis of 75,465 Covid-19 cases in China, airborne transmission was not a major cause of spread.

But Prof Lidia Morawska from Queensland University of Technology said health bodies were underestimating airborne spread. In an an article published in Environment International and co-authored with Prof Junji Cao from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Morawska wrote there were many cases where transmission cause was unclear.

“On numerous cruise ships where thousands of people onboard were infected, many of the infections occurred after passengers had to isolate in their cabins even though hand hygiene was implemented,” she said.

We have more evidence now and we must take it on board

Lidia Morawska

“Therefore, the ventilation system could have spread the airborne virus between the cabins. We know that Covid-19’s predecessor, Sars.CoV-1, did spread in the air in the 2003 outbreak. Several studies have retrospectively explained this pathway of transmission in Hong Kong’s Prince of Wales Hospital as well as in healthcare facilities in Toronto, Canada.”

Morawska said she was worried health authorities were relying on outdated science that suggested staying an arm’s length distance from other people was a way to prevent transmission.

“We have more evidence now and we must take it on board,” she said.

Morawska said reports from Italy that restaurants were reopening, but with partitions between tables, were worrying. “None of these restaurants mention increasing ventilation,” she said. “These partitions will only create more stagnant air and will only make the situation worse. I am worried about what will happen in Australia as discussions occur about reopening restaurants.”

She has written a letter co-signed by hundreds of Australian scientists calling on the government to consider these issues, and she hopes the letter will soon be published by a medical journal. Earlier in May, a group of leading US scientists and doctors launched a petition calling on the World Health Organization to provide clear guidelines on the recommended levels of humidity in public buildings. Morwaska is calling for increased ventilation rate, natural ventilation, avoiding air recirculation, avoiding staying in another person’s direct air flow, and minimising the number of people sharing the same environment, among other measures.

The Rapid Research Information Forum chaired by Australia’s chief scientist Dr Alan Finkel, advised the government that Covid-19 “is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets, although aerosol transmission may also be possible”. The review referred to evidence from China that high temperatures and high humidity reduced transmission of Covid-19.

Related: The indispensable nation? Covid-19 tests the US-Australian alliance

However La Trobe university epidemiologist Prof Hassan Vally said it was important to note that just because a virus could become aerosolised, it didn’t mean those particles were infectious, nor did it mean that it represented a major route of transmission.

“To date, attempts to answer this question in the real world have suggested the virus can be aerosolised but these studies have generally not addressed the viability of the virus,” Vally said. “More theoretical approaches to answer this same question have suggested that the virus may be viable in aerosols for up to three hours, but it is not clear how these laboratory studies translate into the real world. As a result the answer to this question remains unknown.

If you don’t pay attention to it, you will have infected staff and patients

Dr Paul Preisz

“What we do know, however, is that social distancing and hand washing have been effective in reducing the spread of the virus and so this would suggest that direct person-to-person contact is the most important mode of transmission.”

A professor of infectious diseases epidemiology, Allen Cheng, described airborne transmission of Covid-19 as a “controversial area”.

Cheng said detecting the nucleic acid (the DNA or RNA) of the virus in air particles did not mean those particles were infectious, “just as detecting DNA from a prehistoric body doesn’t mean they are alive”. Factors such as humidity and temperature are also important factors in determining virus viability in the air, as are the turbulence and distance with which particles are propelled, and how long particles stay suspended in the air.

But Cheng said there were certain medical procedures that can generate airborne spread even in diseases primarily spread by contact. These “aerosol generating procedures” spread particles further than through coughing, breathing, sneezing or talking. Procedures like tracheal intubation – routine at the start of most surgical procedures and in intensive care units – open suctioning, manual ventilation before intubation, turning the patient to the prone position and cardiopulmonary resuscitation all carry an aerosol risk.

Related: Coronavirus map of Australia: how many new cases are there? Covid-19 numbers, statistics and graphs

Dr Paul Preisz, an emergency medicine specialist at Sydney’s St Vincent’s hospital, said the hospital, along with other major tertiary hospitals, had specialised negative pressure rooms where those aerosol-generating procedures could be performed.

“We built them early after coming out of ebola,” he said. “We can put the patient in the room and change the room settings so air blows out almost like a vacuum and into a separate circulation system so it doesn’t contaminate the hospital.

“We are all very careful with this, and it’s one of the most important measures we have, because if you don’t pay attention to it you will have infected staff and patients.”

Email: sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter

App: download it and never miss the biggest stories

Social: follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter

Podcast: listen to our daily episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or search "Full Story" in your favourite app

Associate Prof Euan Tovey, an aerobiologist from the University of Sydney, said there was an urgent need for high quality research into airborne spread. He is in the early stages of designing studies to examine this in Australian patients. He said people should not confuse low risk of airborne spread with no risk at all.

“The way I think about it is there is less clear delineation between separate routes of transmission, and they overlap more than we realise,” he said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News