Plummeting temperatures force Afghan families back into cracked homes as quake aftershocks persist

Should they face the cold or the cracks? As night-time temperatures plummeted to zero degrees, Masoud Fayeq Alkozai decided it was time to leave the tent and return indoors.

It was an agonising decision. After a series of violent earthquakes devastated Afghanistan’s Herat province in early October – killing at least 2,000 people, including Mr Alkozai’s nephew – the 37-year-old, his wife and two young sons fled their home and took shelter under tarpaulin.

With aftershocks continuing to jolt the region, their structurally damaged house no longer felt safe. But 12 days ago, concerned their sons Adib and Moez were getting sick as the temperatures plunged, Mr Alkozai and his wife went home. Now they’re warm but on edge.

“It’s impossible right now to live in the tent in the open because the weather has got very cold during the night,” Mr Alkozai, an aid worker for Islamic Relief, told the Telegraph. “So we were obliged to come home and live under the cracked ceiling.

“But my children are very scared. The cracks are getting bigger and bigger as there are still aftershocks – we fear it may collapse at any moment and we will lose our lives like so many others we know. But I think there is no other option. We must just continue,” he said.

Between October 7 and October 15, Herat province in western Afghanistan was hit by four back-to-back earthquakes, each registering a magnitude of 6.3. This seismic cascade was interspersed with frequent and ongoing tremors, which have left people in “a persistent state of anxiety and fear”, the World Health Organization has said.

Seven weeks later people are still struggling to recover, with shelter a central issue. Remote villages in the province remain flattened and much of Herat city, a centuries-old citadel, is structurally unsound.

According to a response plan issued earlier this month by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 48,000 homes were destroyed or damaged, alongside 144 schools and 40 health centres. Some 37,000 families have been forced into makeshift tents and open spaces, and a further 8,800 resorted to temporary shelters.

“[These] do not provide adequate protection from the elements,” a separate situation report from the International Federation of Red Cross warned this week. “As winter approaches, it is essential to provide more sustainable and durable shelter solutions to protect the affected families from the cold weather.”

But amid significant funding gaps – OCHA has estimated that $173 million is needed to help 275,000 people in the region, but just $37.5 million has been received to date – assistance is stretched, and many of those who have the option of returning home are doing so despite the risks.

“Even if those homes are now more vulnerable to further earthquakes, shocks or other extreme weather … [some] have decided to go back due to the extreme cold,” said Arshad Malik, Save the Children’s Afghanistan country director. “They do not have any other option.”

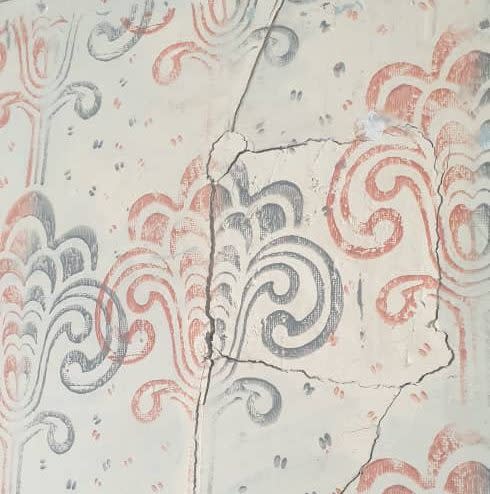

For Mr Alkozai, there is little end in sight; with a salary of around $400 a month, there’s limited spare cash to repair his home in Herat City. Photos shared with The Telegraph show long, forked cracks covering the walls and ceiling.

“I’m not an engineer, so it’s hard to know exactly how risky they are,” he said. “All I know is the house is cracked, the cracks are getting bigger … but I can’t fix my home right now because I don’t have the money right now. I think it is the same for most people, I am not aware of many houses across Herat city that have been fixed.”

The 37-year-old, who has been distributing aid in the worst hit villages for Islamic Relief, added that thousands of people across the region are struggling with their mental health. Not only does the future feel uncertain, but many have suffered significant loss – including him.

When the first earthquake struck, Mr Alkozai’s sister-in-law scooped up her disabled son Arian and ran out of the house seeking safety. But as the ground trembled she lost her footing and fell – Arian crashed to the ground and struck the back of his head. Unable to find medical care amid the chaos, the 12-year-old died the following day.

“We lost my sweet, sweet nephew,” said Mr Alkozai. “My brother – you know, it’s very hard for any parent to lose a child. He is very worried every time there is another mini earthquake, that it could kill his other children.”

The exact death toll varies by source, but almost certainly exceeds 2,000 people. According to Yahya Kalilah, head of programs at Medecins Sans Frontieres in Afghanistan, health teams have encountered many patients who are the sole surviving member of their family.

“Many individuals [are] in need of mental health support to cope with the trauma stemming from the earthquakes,” he said. He added that assessments have identified “significant needs for shelter”, and there are concerns the inadequate housing is making children sick.

“Our medical teams at the Herat Regional Hospital have noticed a surge in respiratory tract infections among children,” Mr Kalilah said. “Typically, winter brings an increase in respiratory conditions as temperatures usually drop several degrees Celsius below zero, but this year’s spike is also suspected to be related to people sleeping outdoors in tents.”

He added: “The most challenging aspect ahead will be reconstruction, which includes restoring healthcare facilities damaged during the earthquakes.”

Amid these challenges, many across Herat are losing hope.

“People are very sad about their futures in this area,” said Mr Alkozai, speaking to the Telegraph via WhatsApp this week. “They don’t have anything to rebuild their houses, they fear that at any time an earthquake could happen again and destroy their cracked houses, and that aid organisations will leave in three or four months.

“The situation is very horrible.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News