The crazy ways humans are trying to control the weather

The world was shocked by the record-breaking rainfall in Dubai last month.

The desert city was inundated with more rain in a few days than typically falls in an entire year, killing at least 20 people across the United Arab Emirates and neighboring Oman.

It was also surprising that many blamed the downpour on something other than Mother Nature.

“The cause is actually from the use of weather modification,” filmmaker Robby Starbuck tweeted. “Play God, find out,” another person echoed.

Johan Jaques, a meteorologist for environmental tech firm Kisters, claimed the storm was brought on by cloud seeding, a method long used by the UAE for inducing rain by injecting clouds with silver iodide.

But the growing consensus is that cloud seeding had little or nothing to do with it.

“Highly, highly, highly improbable,” said Steven Siems, co-chair of an expert team on weather modification at the World Meteorological Organization. The UAE has “been cloud seeding for more than 10 years and never encountered such a storm,” he told the Post, adding that UAE’s meteorology agency revealed that no seeding missions had been conducted prior to the storm.

Even if cloud seeding hadn’t caused flooding in the desert, it brought to light just how invested the Middle Eastern nation is in weather manipulation.

The UAE has spent millions over the last few decades in “rain enhancement” projects, with 300 seeding missions planned this year alone.

They don’t use traditional cloud seeding, in which planes fly into clouds to release the chemicals.

Instead, they employ drones to shoot clouds with electrical charges.

Scientists in the UAE reveal that seeding clouds can boost rainfall by up to 25%.

Playing God with the weather is not just happening in the Middle East.

More than 15 years ago, for instance, China spent billions to keep the 2008 Beijing Olympics rain free, while more recently Beijing — which has also toyed with cloud-seeding rockets — announced plans to develop a weather modification system by 2025 that could provide rain (or lack of it) on command.

Drought-prone Iran, meanwhile, has long dabbled in cloud seeding, and Bangkok has used it to combat smog.

In 2021, the U.K. launched the Advanced Research & Invention Agency (with a $997 million investment from taxpayers) to conduct research on weather control.

Eleven US states — California, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, North Dakota, Utah, and Idaho — have cloud-seeding programs, which everyone from farmers to politicians fiercely defend.

In Wyoming, former state Rep. Evan Simpson insisted that the state’s $1.1 million investment in the practice is “not voodoo.”

And the science backs him up, with research indicating that cloud-seeding can produce up to 10% more precipitation than would have occurred naturally.

“It’s easy to see the impact cloud seeding can have, and the trust and faith local farmers and ranchers have in the program,” said Jonathan Jennings, project meteorologist for the West Texas Weather Modification Association.

And cloud seeding is just the beginning.

If researchers are to be believed, we’ll soon be able to control our weather in ways that once seemed like science fiction.

A Norwegian startup called OceanTherm is developing perforated pipes called “bubble curtains” that can cool the ocean and slow down hurricanes.

Paris researchers reported last year that they’d successfully used lasers to control lightning strikes.

And in Japan, the Moonshot Research and Development Program, launched in 2019 (at a cost of about $1.3 billion in seed money), is developing giant wind turbines designed to “suppress heavy rainfall by about 20%,” said Kosei Yamaguchi, a professor at Kyoto University’s Disaster Prevention Research Institute involved in the research.

Just how realistic is any of it?

Jeroen Oomen, a Utrecht University professor and author of “Imagining Climate Engineering” (Routledge, 2021), calls full weather control “a pipe dream” and “nearly impossible.”

At least not in any great measure at this current moment.

But Karen Bradshaw, an environmental law professor at Arizona State University, claimed “there’s no doubt (weather manipulation) exists. Normal people are just unaware.

It sounds like something from a James Bond movie, but it’s very real.”

The timeline is also open to debate.

Siems thinks we’re still “decades away” from meaningful weather manipulation, while Yamaguchi expects that their typhoon-squashing wind turbines will be ready for indoor model testing “within the year, and then outdoor testing in the next five years.”

In addition to turbines — each about 720 feet high, roughly the size of Times Square Tower — Yamaguchi and his team are also working on a “giant curtain,” pulled by a kite attached to a boat, that would “directly suppress wind velocity, which in turn reduces water vapor flux, thereby suppressing heavy rainfall,” he said. “We are also considering using the curtain to…create rain at sea and preventing heavy rain on land.”

Florida International University professor Hugh Willoughby doesn’t buy it — “My Japanese colleagues are usually much better than that,” he told The Post — and his cynicism is earned.

During the 1960s, he was a head scientist on Project Stormfury, the U.S. government’s failed attempt to weaken tropical cyclones with silver iodide.

Today’s weather manipulation scientists are just “dressing up and recycling discredited mid-20th-century ideas with 21st-century gizmos,” Willoughby said.

To his point, there are more examples of weather manipulation failing than succeeding. Israel ended their cloud seeding experiments last year after decades of disappointing results.

There have been a myriad of weather manipulation ideas that never quite worked, from “Dyn-O-Gel,” a powder peddled by a Jupiter Beach, Fla.-company in the early 2000s that allegedly stopped hurricanes by turning moisture into a gooey gel, to an anti-hail cannon that fired shock waves into thunderclouds.

And in 2008, the Russian Air Force, en route to disrupt a rainstorm with silver iodine, liquid nitrogen, and cement powder, accidentally dropped their cargo on a suburban Moscow home instead of a cloud.

Another problem, said Oomen, is that historically weather control science has “always been connected to nationalistic and military ideas.”

This was certainly true during the Vietnam War, when Operation Popeye attempted to use cloud-seeding to slow down the enemy. (The practice was outlawed by the UN in 1976.)

In recent years, it’s mostly been the stuff of conspiracy theories, whether it’s Iran accusing neighboring nations of stealing rain with its cloud seeding experiments, or rumors that circulated online last January that snow had been manufactured by devious forces “to rig the Iowa Caucus.”

Altough weather manipulation remains unproven, companies are still pushing forward with new inventions.

Olav Hollingsaeter, a retired submarine officer in the Norwegian Navy who now serves as CEO for OceanTherm, said he was inspired by the devastation from Hurricane Katrina, which was fueled by warmer water temperatures.

“Bubble curtains,” the company’s still-unproven tech, involves perforated pipes submerged into deep ocean waters that release compressed air.

“Bubbles will rise towards the surface and entrain the surrounding water on their way up,” Hollingsæter tells the Post. “Done correctly, this will create a well-mixed upper layer with colder water.”

During hurricane season, OceanTherm hopes to deploy “a fleet of vessels” carrying “about 60 miles of bubble curtains,” said Hollingsæter.

Although they’re still in the experimental phase, their simulations have shown that just a 2-degree celsius reduction can reduce hurricane intensity “by about 15%,” said Hollingsæter.

Real world results, beyond just simulations, are now happening in the realm of lightning control.

A classical Franklin lightning rod can only offer so much protection from lightning strikes—which cause billions of dollars of damage every year in the US — and is virtually useless for airports or other large structures, said Aurélien Houard, a research scientist at Ecole Polytechnique in France.

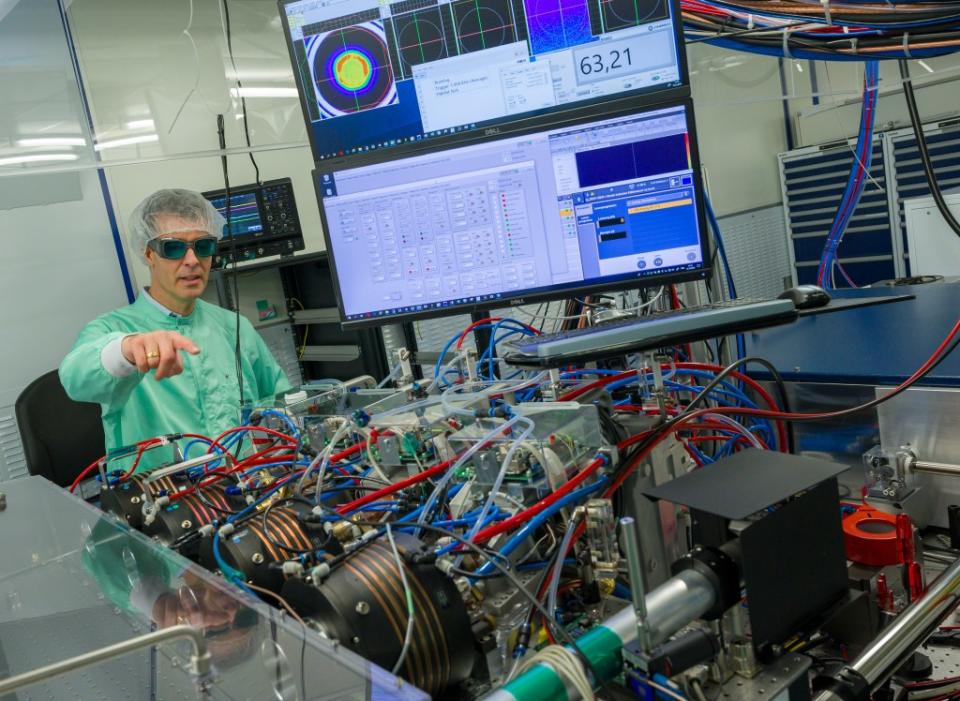

So in January of 2023, he and other researchers tested a terawatt laser, roughly the size of a car, on Säntis Mountain in northeastern Switzerland, a hot spot for lightning activity.

The laser fired picosecond pulses that “ionized the air, creating very long channels of plasma over 50 to 100 meters,” said Houard. “These plasma channels can guide lightning very efficiently.”

In layman’s terms, the layers push lightning in a different direction.

The experiments worked, with lighting strikes on Säntis guided safely away by over 65 yards.

But Houard and his team are working on improvements, capable of sending lightning miles in the other direction. But that, Houard said, would take “a bigger laser,” which could take decades to build and test.

How many of these big ideas become a reality remains to be seen. Some critics, like Oomen, worry that bold claims by scientists could lull the public into a false sense of security.

“We should make sure we don’t over-promise what it can do,” he said. “People will start to think it is a technological solution to a systemic problem, [and] we have to be less concerned about climate change. It really doesn’t.”

But Bradshaw believes we should be paying closer attention to the science, not less.

When discussing her work recently, she noticed that friends and colleagues were uncomfortable with weather manipulation. “People associate any discussion of cloud seeding with chemtrails. They’re automatically skeptical.”

But they should be more curious and even concerned, Bradshaw said, before the technology reaches a tipping point and “private actors can unilaterally affect the weather than affects millions of lives.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News