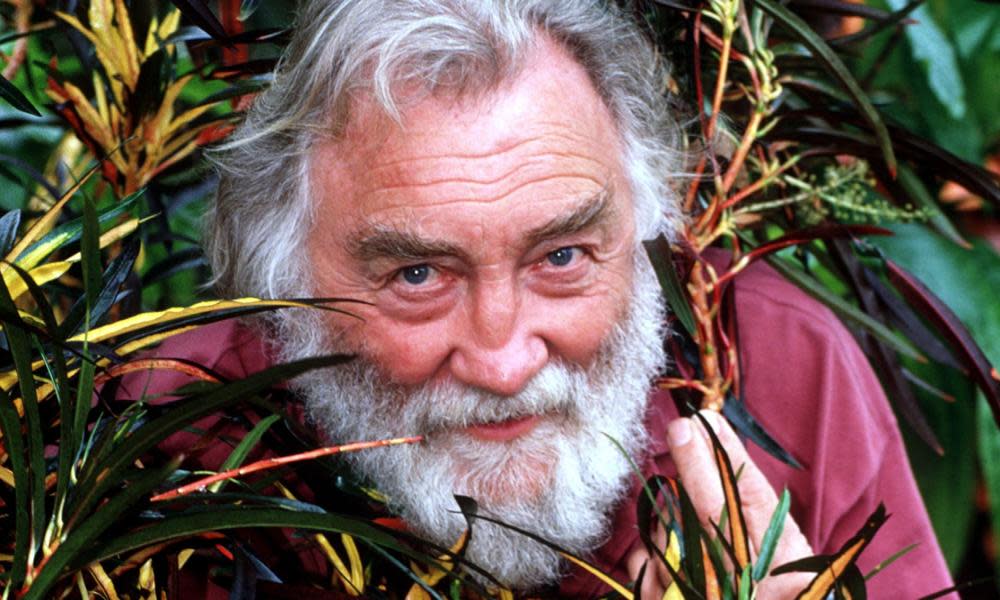

David Bellamy obituary

The botanist David Bellamy, who has died aged 86, fired the imagination of millions of television viewers with the beauty and complexity of the natural world – and our impact upon it. For a generation, his instantly recognisable facial features, surrounded by white hair and matching beard, became synonymous with energetic, vibrant and thoroughly compelling explanations of how our world works. His enthusiasm for his subject, delivered in a style and voice that were as distinctive as his face, held viewers enthralled.

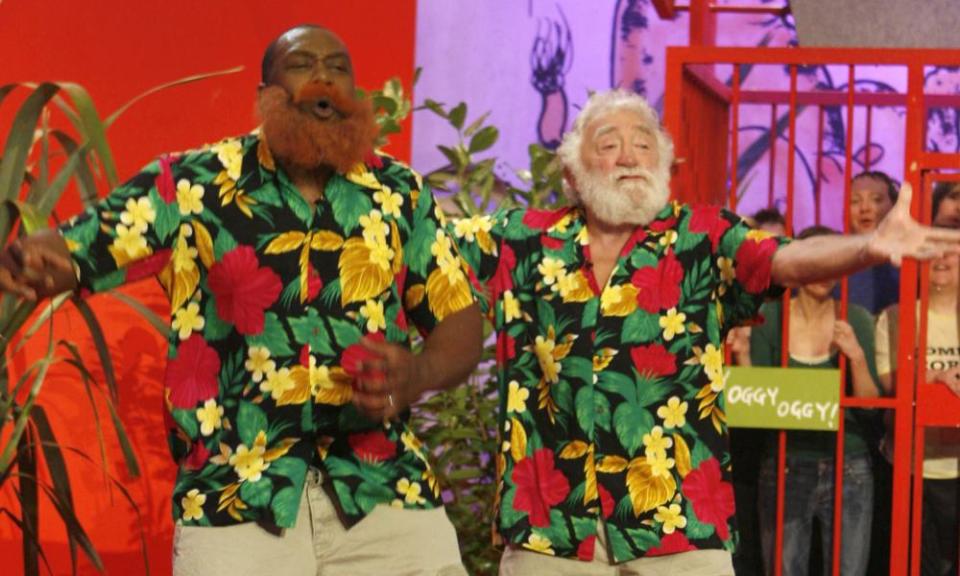

The warmth and honesty with which he delivered his subject brought environmental issues to life. Shows such as Bellamy on Botany (1973), Bellamy’s Britain (1975) and Bellamy’s Backyard Safari (1981) allowed him to develop his trademark attention-grabbing methods, such as surfacing from a pond or river, head covered in foliage, as he explained deposition of silt, say, or the process of photosynthesis. Such eccentricity made him a natural target for imitation, notably by Lenny Henry, which he took in good humour and even appeared to relish, appearing on his TV show, as well as many children’s programmes and chat shows.

The son of Winifred (nee Green) and Thomas Bellamy, David was born in London, into a Baptist family: religion featured prominently during his upbringing and he retained a strong Christian faith all his life. By the time he was six, he had survived pneumonia and acute nephritis. Somehow he survived the second world war years as well: the danger he was exposed to came more from the magnesium fireworks he made as a child, by filing down incendiary bomb cases, than from enemy action.

His obsession with pyrotechnics was curtailed only by an accident that put one of his co-conspirators in hospital. His attention was then drawn to healthier pastimes. An early desire to become a ballet dancer was frustrated when he realised that his “weight to ankle” ratio was not conducive to the profession: as he put it, his “mass exceeded my aspirations”.

He chose science instead and after Sutton grammar school and a first job as a lab technician at Ewell technical college, he gained a BSc from Chelsea College of Science and Technology (now part of King’s College London) in 1957 and went on to do a PhD at Bedford College, London University. At Ewell he had met Rosemary Froy and they married in 1959. The following year he was appointed lecturer in botany at Durham University.

He was discovered by the BBC in 1967, when he was interviewed about the Torrey Canyon oil spill, and his first programme was Life in Our Sea (1970); thereafter his output was prolific. He wrote and presented more than 400 TV series and programmes in the UK, the far east and in Australasia, on botany, ecology and the environment. His 40 books include Botanic Man (1978), and Bellamy’s Changing Countryside (1987) and an autobiography, Jolly Green Giant (2002).

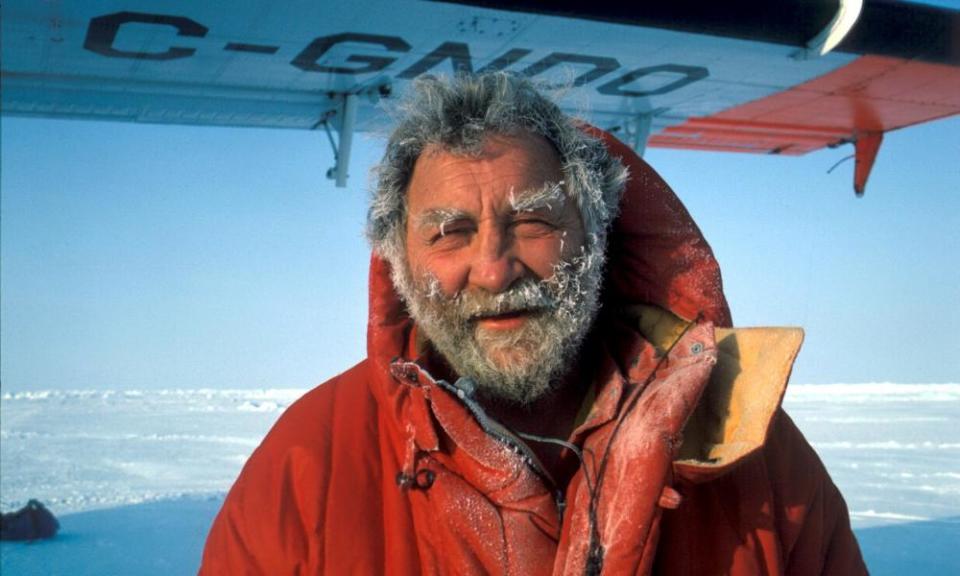

Bellamy was not reluctant to use his body as well as his brain in defence of the environment. In the 1980s, his growing celebrity in Australia and New Zealand led him to offer his support to groups protesting about the planned damming of the Gordon River in Tasmania for an unnecessary hydroelectric scheme.

Receiving little response in the UK to his appeals (apart from a donation from Spike Milligan), Bellamy went to Tasmania and stood on the picket lines himself, with 1,200 other protesters. Arrested and refusing to accept bail, he spent his 50th birthday in jail and enamoured himself to a generation of protesters.

He would never turn his back on an idea that appealed to him, no matter how improbable. Countless initiatives were given a boost by Bellamy’s unflagging energy as, often with the help of the Conservation Foundation, which he established in 1982 with David Shreeve, he endorsed and supported a wide range of projects and ideas.

He maintained his academic career throughout, at Durham as senior lecturer (1968-82) and professor of adult and continuing education (1980-82), and as professor of geography at Nottingham University from 1987. He was also an honorary professor of the University of Central Queensland (1999). In 1994 he was appointed OBE.

Despite his close association with the environmental lobby over three decades, during which he was president, vice-president, trustee, patron or honorary member of dozens of organisations, in later years Bellamy became disillusioned with mainstream green organisations. He saw them as unrealistic where he was a pragmatist, and sentimental where he was a realist. He antagonised animal rights groups by his ambivalence towards hunting and upset greens with increasingly vociferous attacks on windfarms.

He became dogged and unrelenting in his dismissal of climate change. His questioning of the scientific basis for the assertion that anthropogenic carbon emissions are the primary drivers for climate change alienated him from his natural constituency and caused some of his former allies to view his pronouncements – some of which amounted to outright denials about global warming – with scorn. In 2004 he had a well-publicised spat with the Guardian journalist George Monbiot, who accused him of causing “incalculable harm to environmentalism”.

In the 1997 election Bellamy stood as a Referendum party candidate against John Major, a decision he later regretted. His views were seen as increasingly extreme and his figurehead positions with some organisations began to be seen by their trustees as a liability. He appeared to some to present himself as a lone voice of contradiction to compensate for a waning media profile that he found difficult to accept.

To others, his alternative views and his deep convictions, whether they followed the trend or not, were all part and parcel of the man, and came with the privilege of knowing such a warm, considerate, immensely knowledgable and affectionate person who did much good, and re-engaged a generation with the natural world.

Bellamy’s 80th birthday was celebrated with a lecture at Buckingham Palace. The Duke of Edinburgh and more than 100 friends and colleagues attended the inaugural David Bellamy lecture, now an annual event.

Rosemary died last year, and a daughter, Henrietta, died two years ago. He is survived by two sons, Rufus and Eoghain, and two daughters, Brighid and Hannah.

• David James Bellamy, botanist and environmentalist, born 18 January 1933; died 11 December 2019

Yahoo News

Yahoo News