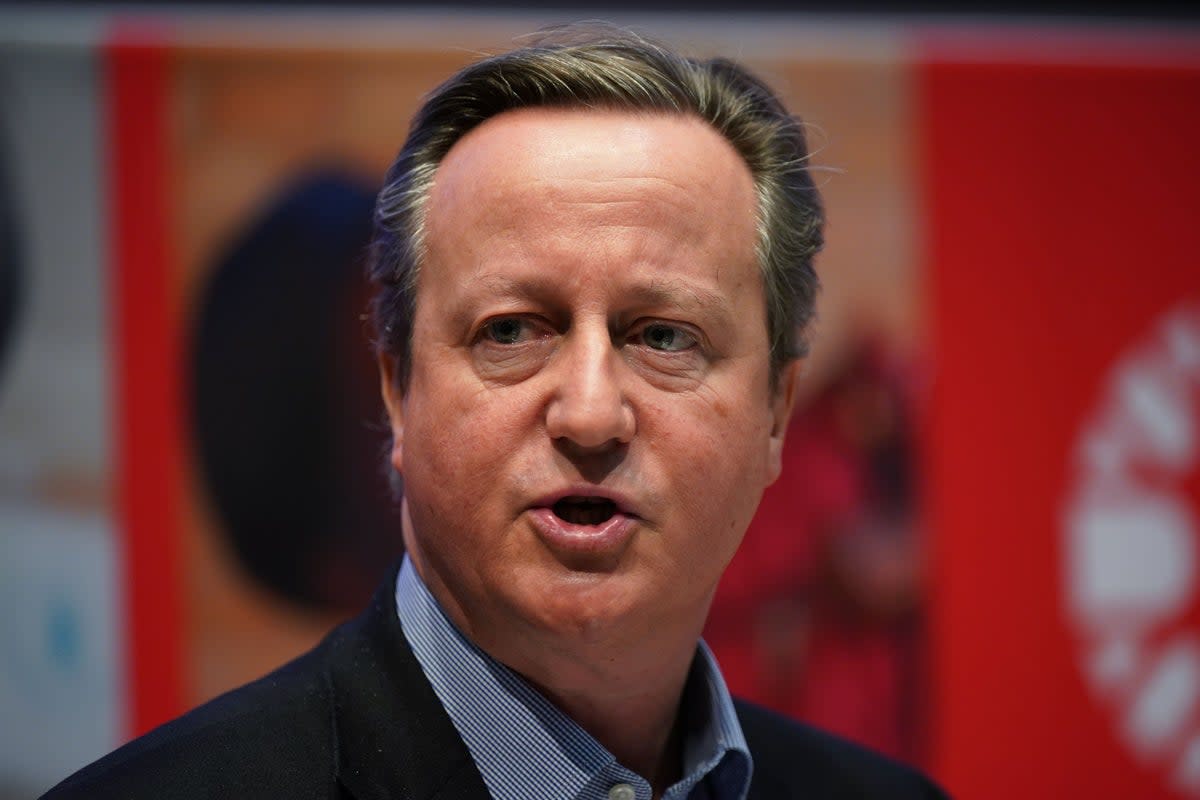

What has David Cameron been doing since resigning from government?

David Cameron has made a surprise return to government after Rishi Sunak sacked home secretary Suella Braverman on Monday morning and reshuffled his Cabinet.

Ms Braverman was fired by Mr Sunak after making inflammatory comments in a newspaper article for The Times, which had not been approved by 10 Downing Street, accusing the Metropolitan Police of exhibiting bias in its approach to political demonstrations.

After far-right marchers descended on London on Saturday for Armistice Day, intent on disrupting a pro-Palestine demonstration that she had branded a “hate march”, violent clashes with officers erupted, over 100 arrests were made and Ms Braverman was widely blamed, leaving her position untenable.

Mr Cameron, who appeared alongside Mr Sunak and other ex-prime ministers at the Cenotaph in Whitehall on Remembrance Sunday, has since been granted a life peerage, enabling him to succeed the Home Office-bound James Cleverly as foreign secretary despite no longer being an elected MP.

The move marks a remarkable political comeback for Mr Cameron, who was elected Conservative Party leader on 6 December 2005, succeeding Michael Howard, led a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats from May 2010 and then a Tory majority administration from May 2015.

Follow all the latest on the Cabinet reshuffle on our live blog.

His tenure in Downing Street ended on 13 July 2016 after the referendum on Britain’s future within the European Union (EU), which he had called, ended with a narrow win for the Leave campaign, prompting the pro-Remain PM to step aside. He duly stood down as MP for Witney in Oxfordshire in September 2016.

Since then, the former PM has taken on the chairmanship of the National Citizen Service Patrons, the presidency of Alzheimer’s Research UK and a number of other positions approved and listed by the government’s Advisory Committee on Business Appointments.

These include roles as a consultant to the US biotech company Illumnia and the financial services provider the First Data Corporation, the vice-chairmanship of the UK-China Fund and a directorship on the ONE campaign to tackle extreme poverty.

Mr Cameron is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, chairman of the LSE-Oxford Commission on Growth in Fragile States and is a registered member of the Washington Speakers Bureau, which hires out guest speakers for corporate events.

Earlier this year, it was reported that he had also taken on a teaching job, leading a three-week politics course at New York University Abu Dhabi.

Some of the former prime minister’s post-Downing Street activities have attracted scrutiny and occasionally controversy, most significantly in summer 2021 when he was accused of exploiting his personal connections to members of the government to try to secure investment in Greensill Capital, a firm in which he held shares and to which he had served as an adviser since 2018.

Mr Cameron denied any wrongdoing in his capacity as a lobbyist but conceded that he should have communicated with ministers via “formal channels” rather than through texts and WhatsApp. The BBC’s investigative programme Panorama would later calculate that his role for Greensill, which has since collapsed, had earned him a cool £7m for what amounted to 30 months of part-time work.

More recently, his lobbying activities were again in the spotlight after it emerged he had flown to the UAE to encourage investment in the Colombo Port City project in Sri Lanka, a key part of Chinese premier Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, which saw him labelled “the smiling face of Chinese interests in the Indo-Pacific” by Politico.

Iain Duncan Smith, one of his predecessors as Conservative Party leader, was particularly critical of that venture, telling the magazine: “Cameron of all people must realise that China’s Belt and Road is not about help and support and development, it’s ultimately about gaining control — as they’ve already demonstrated in Sri Lanka. I hope that he will reconsider the position he’s taken on this.”

A spokesman for Mr Cameron denied that he had had any direct contact with the Chinese government and explained that he had been assigned the speaking gigs in Abu Dabi and Dubai by the Washington Speakers Bureau.

Mr Cameron has otherwise spent his time out of public office residing in the enviable Cotswold town of Chipping Norton and used the Theresa May years to write his memoirs in a £25,000 shepherd’s hut in his garden, which were completed and published under the title For the Record by HarperCollins in September 2019.

He typically kept a low profile while Ms May’s government struggled to negotiate the terms of Britain’s withdrawal from the EU but did later admit in an interview with The Times that the outcome of the Brexit vote had left him “hugely depressed” and worried that “some people will never forgive me” for calling the vote in the first place.

He characterised the Brexit campaign as one in which the “very powerful emotional argument” of the Leave side had overrun the careful technical considerations raised by the Remain camp and said certain Conservative colleagues like Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, Penny Mordaunt and Priti Patel had “left the truth at home”, particularly regarding the realities of immigration, lamenting the “terrible Tory psychodrama” that had ensued.

“Every single day I think about it, the referendum and the fact that we lost and the consequences and the things that could have been done differently, and I worry desperately about what is going to happen next,” Mr Cameron said.

“I think we can get to a situation where we leave but we are friends, neighbours and partners. We can get there, but I would love to fast-forward to that moment because it’s painful for the country and it’s painful to watch.”

He was criticised during the Covid-19 pandemic after it emerged that he had volunteered at a local food bank, the Chippy Larder, an ordinarily-welcome gesture that was, in his case, badly undermined by statistics indicating that dependence on such emergency community resources had risen dramatically over the course of his austerity-led premiership.

Foodbank use went up 2,612% while David Cameron was Prime Minister.

Apologise for that before you start posing for photos, @David_Cameron. https://t.co/99D5qCtHR2— Zarah Sultana MP (@zarahsultana) March 18, 2022

Less controversially, it emerged in March 2022 that Mr Cameron had driven a truck of food supplies to Poland’s border with Ukraine in support of refugees fleeing their homeland in response to Russia’s illegal invasion.

Mr Cameron has since been slowly inching his way back towards the political frontline in Britain, telling LBC in a May interview that he supported the now-ousted Ms Braverman’s plan to relocate asylum seekers to Rwanda as the best-available means of breaking up human trafficking gangs operating along the English Channel.

“If you don’t have a better answer to the things that the government is doing to try and stop this illegal trade, then I think there’s no point criticising,” he said.

“So until you’ve got a better answer, you won’t find me in radio and television studios telling Suella Braverman what to do.”

He was less helpful to Mr Sunak’s administration in September when he criticised the announcement that the northern leg of the HS2 high-speed rail line would be scrapped, calling it a “wrong” decision that meant that a “once-in-a-generation opportunity was lost”.

Anticipating those comments coming back to bite him on Monday, Mr Cameron acknowledged that he “may have disagreed with some individual decisions” by the current government but insisted that he considered his new boss “a strong and capable prime minister”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News