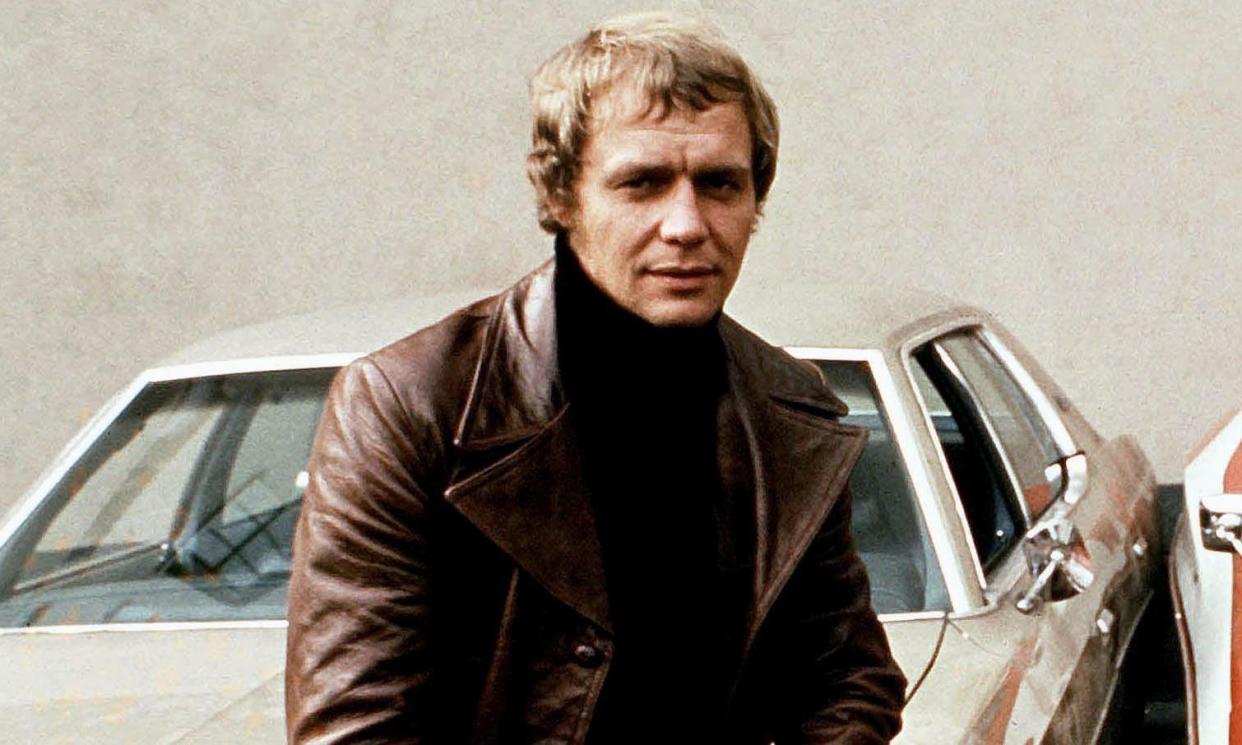

David Soul: the British-American star who made crime-fighting cool

Trying to explain the appeal of Starsky and Hutch to the younger generations, one often falls back on: well, we only had three channels then. With the death of David Soul, aged 80, it’s tempting to repurpose that to explain his popularity, which at times was so intense as to cause a Beatlemania-style moral panic, the New York Times worrying in 1977 that his audiences emitted a “continual squealing”. It was the 70s, and we only had four types of men then: classically handsome, ruggedly handsome, special-interest handsome and funny.

Related: Starsky & Hutch actor David Soul dies aged 80

Soul was rugged, a man with the kind of face that didn’t stop to think about what would happen to his nose when he threw a punch. So was his co-star, Paul Michael Glaser, and it mattered to their vibe that they were so evenly pitched; if you walked into a bar with your best friend, you wouldn’t have a fight about who got which. They pretty much invented the detective bromance, their easy physical affection as novel to the genre as their hipster dress sense and unrufflable side-eyes. There was a rumour, of which Soul said in a documentary in 1999 he’d got wind of, that people in the industry called them “French-kissing, prime-time homos”, a more or less perfect epithet for the challenge they posed to the genre: suck it, grandad. In 2021, Glaser put a throwback pic on to Instagram of his Starsky and Soul’s Hutch, walking down a beach, holding each other by the butt-cheek, wearing matching Husky and Starch T-shirts, so close they’d melded with their roles and, more to the point, each other.

Starsky and Hutch, when it first landed in the UK in 1976, was so immediately popular that the BBC would go to the wire to screen it as soon as possible after the US, and old-timers remember repeats going out on Saturday night because the film hadn’t arrived in time. What’s peculiar is that even on repeat, it seemed exquisitely glamorous, recalling an era where the US just seemed awe-inspiringly better at everything: shinier, sleeker, richer, smarter. We’d watch Starsky and Hutch alongside The Sweeney, and it was the entire story of the “special relationship” written in crime-fighting; Hollywood production values versus rattling doorframes; endless sunshine versus puddles; effortless style against manly indifference. Even their wit was sunnier, ours a lot more mordant. Don’t get me wrong, The Sweeney was also great. But it was an interesting and actually quite long period, the whole back end of the 20th century, when American culture was extremely attractive to British audiences – exotic, somehow larger, paradoxically more flamboyant and more grown-up – but we weren’t trying to ape it. It was just too cool.

In its first two seasons, Starsky and Hutch was hard-hitting and gritty, and looked a lot like an action movie, both in its slick production and, of course, all the car-chasing and fighting. A lot of the storylines were based on real crimes – as unlikely as it sounds, this makes it The Wire of its time – and the detectives themselves had real-life prototypes, who later sued and settled for the endearing sum of $10,000 each. By the fourth and final season, it was more about the characters and the gags, and its mood was more carefree which, along with Glaser’s desire to move on, led to the show’s cancellation. It would never disappear from the cop show lexicon, though apparently only in the UK would passion for it remain so high that we still (as a market) have a thing for Ford Gran Torinos. Both Glaser and Soul hated that car, Glaser for the bulky handling, Soul because it was “more famous than any one of us”.

David Soul joked about never really wanting to let the role go: when it was announced earlier this year that Sony was developing a reboot with female detectives, Soul tweeted: “Why not just reboot Paul and me – as a couple of old farts solving piddly-ass crimes at the assisted-living facility where we would now live? Who can do Starsky and Hutch better than me and him?”

The irony was, our affection for David Soul, this American prince, was so intense that it eventually turned him British: after his success in the UK charts, which began in the mid-70s, he took citizenship here 20 years ago, saying he’d found a place he truly belonged, and wanted to give something back. It was a touching gesture, but unnecessary: he’d already appeared twice in Holby City. We knew he was one of ours.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News