Diet of ancient Andes hunter-gatherers was 80% plant-based, study finds

Hunter-gatherers living in South America around 9,000 years ago had a predominantly plant-based diet – challenging the widely held view that these societies were made up of mainly meat eaters, scientists have said.

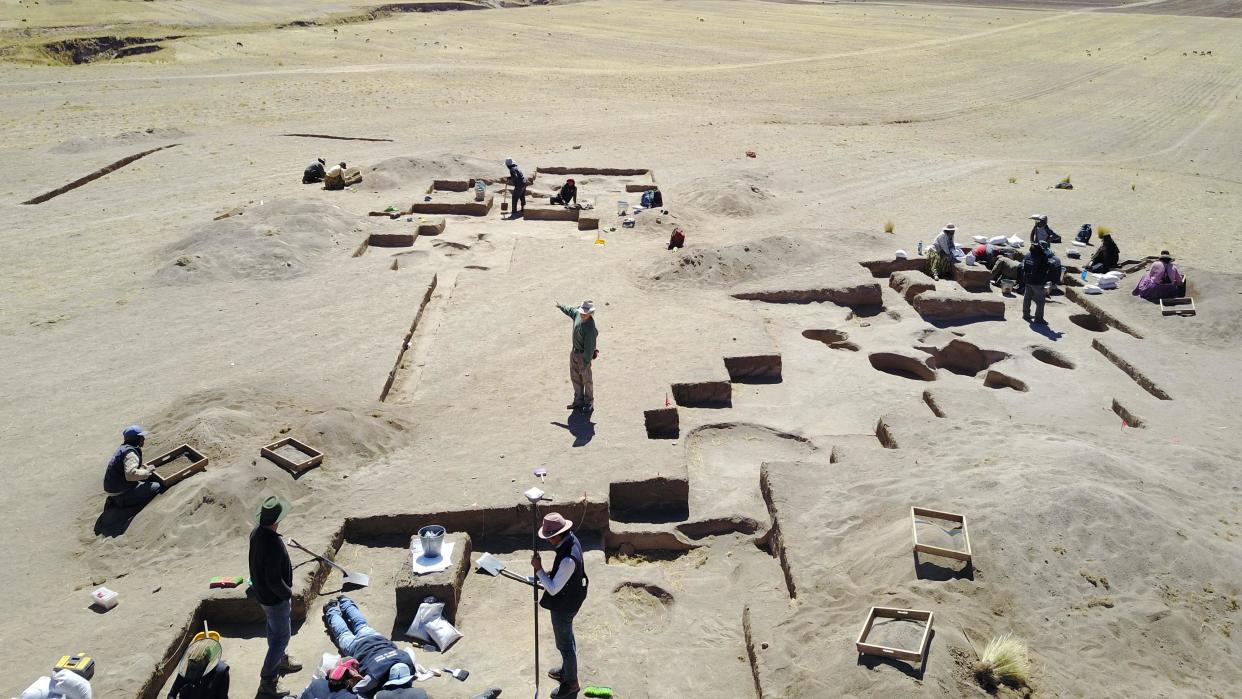

Archaeologists at the University of Wyoming in the US analysed remains of 24 individuals from two burial sites in the Andes Mountains in Peru.

Chemical evidence from the bones revealed plant foods to be a major part (around 80%) of the diets of the Andes hunter-gatherers, with meat playing a secondary role, the team said.

The belief that ancient humans were predominantly meat-eaters has led to approaches such as the paleo diet – which seeks to mimic the eating habits of ancestors who lived during the Paleolithic era, from about 2.5 million to 10,000 years ago.

Today, the modern-day paleo diet is based on meat, fish, vegetables, nuts and seeds, and excludes grains, pulses and dairy products.

While some believe that human bodies are better adapted to the diet of Paleolithic ancestors, critics argue it may be too restrictive, eliminating certain nutritious foods.

Randy Haas, an assistant professor at the University of Wyoming, said: “Conventional wisdom holds that early human economies focused on hunting – an idea that has led to a number of high-protein dietary fads such as the paleo diet.

“Our analysis shows that the diets were composed of 80% plant matter and 20% meat.”

He said one of the main reasons why hunter-gatherers were widely believed to be meat-eaters is because “artefacts associated with hunting preserve better than those associated with plant foraging and processing”.

Prof Haas said: “Stone tools and animal bones preserve well while plant parts tend to rapidly degrade and thus are rarely observed in the archaeological record.”

He also said it is theoretically possible that hunter-gathers such as the Andeans were meat-based to start with and the “transition to a plant-based diet happened much more quickly than previously thought”.

But Prof Haas added that western biases about early human diet cannot be overlooked.

He said: “Archaeology and related sciences have long been dominated by male practitioners.

“In western culture, hunting is the purview of males, which has likely led to an over-emphasis on hunting in the interpretation of early human economies.

“The convergence of these various factors has misled us to overestimate the role of meat in early Andean diets.”

For the study, published in the journal Plos One, the researchers looked at the isotopic composition of the remains found in the burial sites Wilamaya Patjxa and Soro Mik’aya Patjxa.

This method looks at the variations of chemical elements in ancient bones and can provide valuable information about the individual’s diet, where they are from, and other aspects of their life history.

The researchers said that while there is evidence that the Andes hunter-gatherers, who lived somewhere between 6,500 to 9,000 years ago, were killing large mammals for food, this would have played a secondary role in their diet.

The team also found burnt plant remains from the sites.

The researchers analysed marks on the teeth and found patterns that suggested that tubers, or plants that grow underground such as potatoes, were a key part of the diet.

Lead author Jennifer Chen, a PhD student in anthropology at Penn State University in the US, said: “Food is incredibly important and crucial for survival, especially in high-altitude environments like the Andes.

“A lot of archaeological frameworks on hunter-gatherers, or foragers, centre on hunting and meat-heavy diets – but we are finding that early hunter-gatherers in the Andes were mostly eating plant foods like wild tubers.”

The researchers said their work shows, for the first time, that ancient human economies were plant based – in at least one part of the world.

Prof Haas said: “Given that archaeological biases have long misled archaeologists – myself included – in the Andes, it is likely that future isotopic research in other parts of the world will similarly show that archaeologists have also gotten it wrong elsewhere.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News