Director Michael John Warren On Capturing The Rise, Fall And Rebirth Of The Cultural Revolution In ‘Lolla: The Story of Lollapalooza’

Some ideas are outlandish enough to change everything. This is especially the case for one of the world’s most famous and culturally impactful musical festivals, Lollapalooza, birthed in 1991 as a farewell for Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell. The festival quickly became a traveling showcase of ragtag bands and artists ranging from alt-rock, punk, metal and hip-hop that managed to define a generation steeped in radical counterculture.

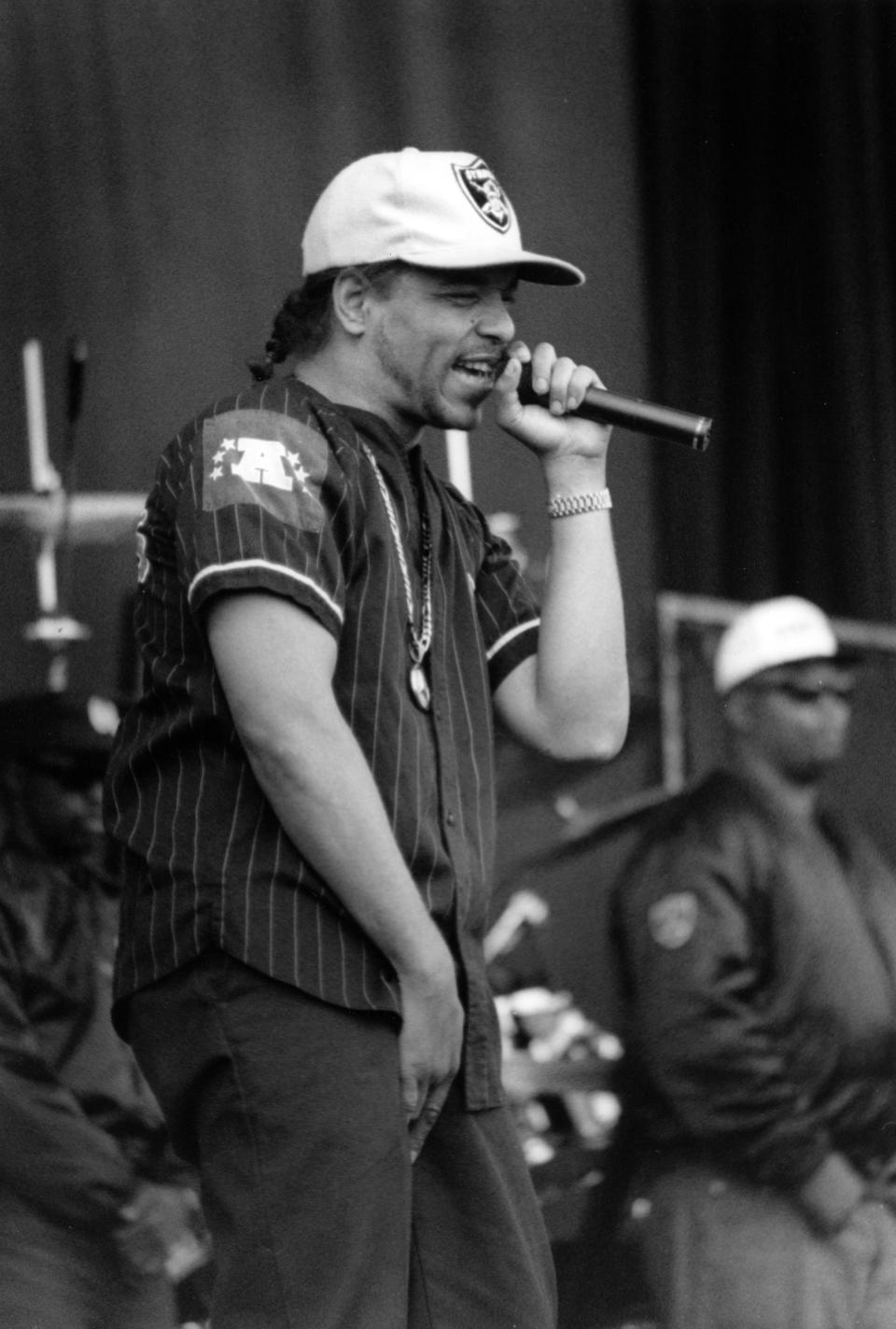

Paramount+’s three-part documentary, Lolla: The Story of Lollapalooza, takes an in-depth look at the festival’s journey through three decades. Through a prime interview with Farrell, archival footage and subsequent interviews with members from Nine Inch Nails, Living Color, L7, Metallica, Ice-T and other legendary musical pioneers, the documentary highlights how Lollapalooza aimed to push the boundaries of the alternative music scene while also battling the challenges of succumbing to the pressures of fame only to evolve into what it is today, a three-day festival based in Chicago’s Grant Park.

More from Deadline

Here, director Michael John Warren talks to Deadline about the process of gathering archival footage, not shying away from the radical racial diversity of the time and capturing Farrell’s inspirational childlike influence.

DEADLINE: How did you get involved with the Lollapalooza documentary?

MICHAEL JOHN WARREN: This is by far the most personal thing I’ve ever made. I was at the first Lollapalooza at 17 years old. They came to my hometown of Mansfield, Massachusetts, and it really spoke to me. We were little punk rock kids who just hated corporations. We hated pop music. We hated all that shiny bullsh*t. We were offended by it, honestly, and Lollapalooza came in with all this super alternative and really progressive and a lot of interesting conversations. It really was an eye-opening moment for me. I hadn’t seen the world yet because I was just living, stuck in suburbia.

Then, a lot of my life happened and this project came around. It almost sounds impossible. That’s why I did it. I was like, “That is such a big idea,” 30 years of what I consider the most influential music festival of all time. When the idea came around, I was like, “That sounds really hard, taking 30 years of this zeitgeisty, cultural-changing, music-industry-changing thing,” and that’s why I did it because, at this stage of my career, I’m really just looking for challenges, and I was like, “That sounds really challenging.” It was really personal for me, and it sounded like a great challenge. I’m very happy I did it.

DEADLINE: Your career is quite varied, but I know you have more singular subjects in there, like Jay-Z, Drake and Nicki Minaj, along with some Broadway stuff as well. Was there a particular challenge in transitioning to focusing on the broader festival at large?

WARREN: There’s some true-crime elements of the American judicial system, and I get a lot of critical acclaim for my sports work as well. But, no, there’s no topic too big. Frankly, there’s nothing bigger and no story more complex than the Meek Mill story and what happened to him in Philadelphia as a young man getting stuck in the judicial system. That timeline that we built when we were telling that story, it went across the walls of the office. It was so complex with all the stuff that happened to him in his life. Once you do something that complex, there’s nothing more complex than what happened to him.

The real challenge is telling a story about an entity, Lollapalooza. It’s really hard to make that emotionally engaging because the way storytellers engage their audiences is by attaching the story to a person. I always knew this was Perry Farrell’s story, and so, when you watch the series, he’s constantly coming back in. He didn’t just found it. He’s still involved with it today. He fell out of love with it. It died. It came back. It died again. He’s going through all the ups and downs with it, and so we rooted the story in Perry. One, because it is his story, but two, because we knew that was the way to keep you emotionally involved as an audience, because telling a story about a festival or a brand or whatever it is that usually doesn’t work very well.

DEADLINE: This is a three-part documentary. Did you ever consider doing a feature? Or perhaps more than three parts? How did you decide to structure the material? There is so much material that you could further explore on its own, especially all the stuff about Ice-T and his band Body Count.

WARREN: It was always going to be a series because it’s just that big of a story. It could have been a feature also, but it would’ve been rushed. If you were going to do a feature on this, you would have just done the year 1991. That could have been a feature. But there’s no way you could have done 30 years of history as a feature. We’ve got to talk about Ice-T. We have to because, anyone who hasn’t seen this series yet, go watch it and get ready for some things that only Ice-T can say and do during that interview. As I was doing that interview, I was like, “I do need 10 episodes,” because everything coming out of his mouth has to go into the show.

It isn’t longer because we wanted to make sure it was well-paced. I think the modern audience wants things that are well-paced. We also wanted to make sure that every second of it was “edge of your seat,” and there’s also just the appetite of Hollywood. There’s not a lot of big, sprawling things happening right now. And [the doc] is all of those things. I actually think it sits really well where it’s at. I do think there could be a 10-hour version of it because, for me, I’m a music fan, nerd, former musician, and all of those things. Still, there’s a version of this where you sit down for a whole song from 1992 Pearl Jam or you sit down with Lady Gaga as she’s headlining or not even headlining. You really sit down with them and experience the performance in a very luxurious way as a concert film.

I do concert films as well. There’s part of me that’s like, “Oh, can we just sit there with Rage Against the Machine for 20 minutes?” There’s that version where you do that and you go deeper into each band, but I think what I love most about the series is it really deals with the cultural context around the music, especially in the early parts of the series. It’s a music story, but it’s actually a cultural story. It’s about a cultural revolution. The beginning of the series is about Gen X’s cultural revolution and how we rejected everything that was before us and just insisted on building our own thing. Then it goes on to just keep talking about youth culture through the prism of Lollapalooza, and it really comes all the way up to present day. It ends in India toward the end of the series because that’s what’s happening currently.

Perry’s mission now is he knows he can’t give an American audience the experience he gave me when I was 17 because American audiences are spoiled. Because of Lollapalooza, festivals became a huge thing. They’re not as big as they were, say, late ’90s, but they’re still huge. He knows he can’t blow anyone’s mind in America really anymore because they have the other festivals out there. If he goes to India, they had never seen anything like that a couple of years ago when he first touched down there with Lollapalooza, and he was just like, “Here,” and they were all like, “This is incredible. We’ve read about this. We’ve seen this, and we’re experiencing it.” Perry loves culture and he really respects different cultures. He makes sure to bring in people from India, or from the local culture of wherever he’s going globally. It’s good business as well. He’s really into showing people something they haven’t seen before.

DEADLINE: How long did it take to put together the documentary and all the archival footage?

WARREN: I think I first started working on this three and a half, four years ago probably. There were some people. My friends at FunMeter were working on this even before I got it cooking. This was a very long process. It’s a very big story. There’s a lot of very famous musicians who had to agree to be interviewed, clear their music. We went through at least 20,000, maybe 30,000 hours of archival footage and had to go through that. This is a well-documented music festival for 30-something years.

At this point, when you go to Lollapalooza, there’s 10 TV trucks filming different stages. There’s so much to go through, and we wanted to add that cultural stuff, so we wanted to talk about the Reagan administration. We wanted to talk about Rock the Vote. We wanted to talk about all the things that are in there. It was at least half a decade in the making without question.

DEADLINE: What was the throughline or theme of the documentary that you wanted to get across to audiences?

WARREN: This is the bizarre story of Perry Farrell’s love affair with something, his own monster that he creates out of love and almost by accident and then it becomes so big that he ends up hating it, and then it just falls over on its self because it’s so big and he’s heartbroken. Then he revives it and brings it back to life, and then he becomes a responsible artist where he’s like, “OK, I’ve got it alive again now. How do I keep it alive forever now?” That’s really what the Chicago part of that story is about. It’s how do I distill and crystallize the things that make this vessel special and make it repeatable so, if I’m not there, they have the formula?

That’s what he’s done in Chicago at this point. It’s a story of codependency. I don’t know if Perry would make it without Lollapalooza, and I’m also not sure Lollapalooza would make it without Perry. It’s a strange story about a guy who creates something and then becomes addicted to it, and it’s addicted to him, and how it spans across three decades of American culture and, now, global culture.

DEADLINE: The coolest thing to me is that it wasn’t just about passively watching a music documentary. I learned so much. I had no idea Lollapalooza was born out of the ending of Jane’s Addiction. And I had no idea that Grant Park had ceased concerts since the riot at the Sly and the Family Stone’s show in 1970, until Lollapalooza approached them in 2005. And now it’s been there multiple times.

WARREN: That’s part of the reason why there weren’t any festivals in America for a long time because of Altamont, that famous Rolling Stones concert where the Hells Angels were security and Meredith Hunter got stabbed. That’s why festivals weren’t really happening for decades before Lollapalooza. Festivals can be a dangerous business. I think we all know that.

When I touched on Lollapalooza in ’21, it was the largest gathering on North American soil since the pandemic had started, literally. They were pioneering all these safety protocols which became commonplace right after they proved that it could be done. When I touched down there, I saw the infrastructure of what happened to Grant Park, the cops, the fire department, the water, they’re watching everyone for like, “Do they need water at Zone 17-B?” literally down to the square footage. They were watching. They were making sure everyone was safe and everything was under control. They take it very seriously because it’s a big deal. I don’t want to get too deep, but you really got to keep the people safe, and they’re very good at that. Back in the day, in 1991, it wasn’t really a thing, and you got Gibby Haynes from the Butthole Surfers firing a shotgun over the crowd. That’s how they grew. They thought that was OK to do in ’91, and now they’re like, “Do they have water in Zone B-12 and B-17?”

DEADLINE: Right, and then you had Rage Against the Machine also showing their genitals in protest as well.

WARREN: Right, and then almost causing a riot themselves. Rage Against the Machine, that’s a band that is so powerful. I mean the lyrics, “F*ck you. I won’t do what you tell me.” That’s a riot in the can right there. They had to manage all that stuff. They want to let the youth express their anger, but how do you do that in a way that’s responsible? It’s great to express yourself, but you can’t hurt people when you do that, and so they’ve really mastered that. It’s interesting.

DEADLINE: Did any research or interview particularly surprise you when creating this documentary? I’m still reeling from learning about Ice-T and Perry’s performance of Sly and the Family Stone’s “Don’t Call Me N—, Whitey” and his contextualization of it three decades later.

WARREN: I knew we were going to get into “Don’t Call Me” because I saw that live when I was 17. At that time, I didn’t even know you could say the N-word on stage. I literally didn’t think it was legal to do that. My mouth was open. I couldn’t believe it. I was literally waiting for the cops to shut the whole day down. I’d been waiting for that all day because Nine Inch Nails was incendiary, and that whole day was really on the edge, and then they come out and do “Don’t Call Me,” and I’m like, “This is done. It’s over. The show is done.” When it didn’t get shut down, I was sure the cops were being held at bay somehow just off in the distance. Because I was so young back then, I wasn’t sure of the intention of all of that at the time. I’ve studied race a lot since then, and I really wanted to tell that story because I was like, “I couldn’t believe it happened.” I think modern audiences are going to be totally shocked at first, but I also think it’s an interesting thing to talk about because we are very sensitive right now. You’ve got to clear the air sometimes.

So I thought, “If we’re going to have a conversation about how to do that, I’m pretty sure Perry Farrell and Ice-T are the two people who could lead us through using that performance as a focusing element,” so I had to get Ice-T because Perry can say what Perry says, but you need Ice-T to have that responsibility put on television in 2024. I wasn’t really sure what he was going to say. I asked him directly, “Was it just for shock value?” He was like, “No. We wanted to prove that racism was stupid.” He’s like, “I’m not the kind of person who can be like, ‘Love your mother. Hug your children.’ I got to hit you with the shock value and then contextualize it.”

I thought that was important because we’re having a hard time speaking to each other as a country right now, and I thought that was a good example to put out there to see: this is how those two did it. They did it in a pretty responsible way. Ice-T isn’t going to do a damn thing Ice-T doesn’t want to do. I thought that might be a helpful tool for us. We don’t have to just not say all the things, and we don’t have to scream at each other about anything also. There’s a way where we can get back to “we don’t have to agree on everything,” or we can get to those touchy topics if we want to as long as we do it responsibly.

I think we did a really good job of contextualizing that performance and making sure we understood what was happening, why it was happening, and how they feel about it 30 years later. I wasn’t sure they were going to still own it, and they were like, “No. We’re both really proud of that.” I’m like, “OK, great,” and now it’s out there for the world. I think there’s a lot of value there. I think we could learn something from what they were trying to do back in ’91 today.

DEADLINE: Many online reviews talk about how refreshing it is that the Lollapalooza documentary doesn’t whitewash the history of how revolutionary the festival was. And I’m curious as to how you managed to tackle that. Surely, it would have been so easy to just stay on the surface.

WARREN: I have read the articles and am glad they’re saying that. But also, it’s like, have you seen any of my other work? Of course we’re going to talk about that, but not just because I want to put race into everything I make, because I don’t. But it was legitimately an important topic to talk about for that show. I was in Mansfield, Massachusetts, in 1991. It was very, very, very white back then. I haven’t been back in a long time. So, I don’t know what it’s like now. But the chances of Ice-T coming to my hometown and doing all of those songs, like “Cop Killer,” by the way, without Lollapalooza, was impossible. It wasn’t going to happen. I knew we had to talk about that because it was like Perry was introducing hip-hop culture to suburban America at that point. Hip-hop was exploding. We knew about all that stuff, but Ice-T wasn’t going to come to Mansfield, Massachusetts, without Lollapalooza, and so it was really important to talk about that. When you get into the “Cop Killer” conversation in the documentary, it’s interesting because that’s even more relevant than the “Don’t Call Me” conversation.

Rodney King had happened right around that time. We were mortified that that was going on, and then here comes “Cop Killer.” It’s like a Molotov cocktail of a song. He just chucks it out there, and you’re like, “Holy sh*t.” We talk about race a lot in that series because that’s one of the major things Lollapalooza was doing. They knew that the race conversation had to keep going. It didn’t end, obviously, with the Civil Rights era. We have to keep going. We’re still going now. We leaned into it, but it was also right there. It was like, of course, we’re going to talk about those things.

DEADLINE: What was something interesting that you wanted to make the cut so bad, but no matter how hard you tried, you had to let it go?

WARREN: That’s tough because a lot of times when you are trying to get something down to time, the things that go are the things that aren’t necessary, but you really do love them because there’s a joke or a little aside that isn’t fundamental to the structure. You can’t let the structure fall apart when you come down at time, and so little jokes here and there. There was a lot of footage. Perry’s girlfriend at the time, in ’91, had a camcorder with her. She’s backstage. She’s in all the rooms. She’s there. That’s where all that Ice-T going through the audience footage comes from, and so there was more stuff. There’s more Ice-T out in the audience, which is just like, “Let’s just put that raw up there because there’s a lot of them.”

But there was a lot of cool little gems in there that had to come out for time. Like I mentioned earlier, there’s a version of the show that is 10 hours long, and we lean into these performances because some of these performances are absolutely jaw-dropping and, instead, you get a taste of the performance, but it’s really a story-centric series that is paced well. We’re moving through 30 years in three episodes. It’s aggressively paced. It’s very story-driven more so than like, “Let’s hang out with Chance the Rapper for two songs.” We can’t really do that in this. I do think that this is the best version of the show. The one that came out is the best version. There’s a more luxurious and music-nerd version of this that could have come out, but I don’t think that would have served the general population, frankly.

DEADLINE: What were the most challenging parts to assemble?

WARREN: Building this episodically. Although the material is so rich getting episode one down to time, like I said earlier, there’s a world where we put out a very good 90-minute film just on that first episode. I’m not even trying to be funny. Episode 1 is so good. It’s briskly paced, and it’s great, but there’s a longer version of that where you dig into even more of that stuff. You let the music play a little bit more, and you give Siouxsie and the Banshees a little bit more shine. So, getting that to fit into a tight little package was challenging. Making sure we contextualized the cultural side of the festival as well, telling the Chicago story, making sure that we made sure to show that all of Chicago wasn’t really happy when it first showed up. I think that was an important part to include. From what I can gather now, Chicago seems to have made their peace and maybe some of them even love Lollapalooza at this point, but when they first got to Chicago, a lot of people were like, “What the hell are you talking about? You can’t let a festival take over our park.” Chicago is like New York, Boston and Philly. They’re not going to really pull their punches. They’re going to say what they’re going to say whether you like it or not.

I think just making sure we didn’t just get lost in the music and the hype, and we really wanted to contextualize things was the challenge. I love that Perry is willing to admit his mistakes and own them. He understands he’s not perfect. An important part of being an artist, honestly, is you get to know that 90% of your ideas are actually bad or flawed. If you can get 10% of good ideas out there as an artist, you’re actually killing it. He knows that, and so he’s not really afraid of his failures and he really does want to own it. I really respect that for him.

I have to say, as a somewhat prolific artist myself, it was really interesting interacting with him because he’s older than me and has really stayed after it. It was really good to see someone who is still kind of a child, and I mean that in a good way, has that awe and wonder, that ability to be open-minded. I was like, “OK, you really could take that all the way to the end of your life if you cultivate that feeling and that sensation and you know how to keep your eyes up and your ears out there,” and he does.

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity]

Best of Deadline

Hollywood & Media Deaths In 2024: Photo Gallery & Obituaries

All the Surprise Songs Taylor Swift Has Played On The Eras Tour So Far

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News