Doctors see increase in frostbite cases among Calgarians living in poor housing conditions

A couple of podiatric surgeons in Calgary are sounding the alarm about a concerning change at the hospital they say is spurred by the city's housing crisis.

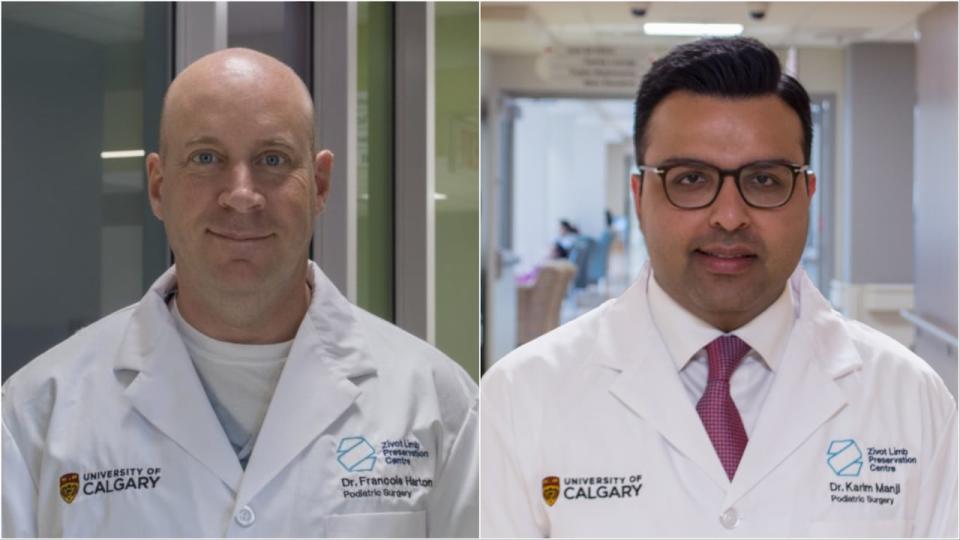

Dr. Francois Harton and Dr. Karim Manji specialize in treating diabetes-related foot conditions with the Zivot Limb Preservation Centre at Peter Lougheed Centre in northeast Calgary. Their main goal is to prevent limb amputations.

But when extreme cold hits Alberta, they're also among those at the forefront of frostbite treatment.

Both doctors joined a call with CBC News during the recent cold snap. They said usually, the majority of frostbite cases they see at the hospital are among people experiencing homelessness. But that's changing.

Lately, Harton and Manji have seen more Calgarians who are living in poor housing conditions come in with frostbite — sometimes acquired while inside their homes.

"I think there's a stigma attached [that] it's only a certain type of people that get frostbite in society, and it's not," said Harton.

"Unfortunately, we're seeing a greater shift now on people who just live in sub-optimal conditions."

Dr. Francois Harton and Dr. Karim Manji are podiatric surgeons at the Zivot Limb Preservation Centre at Peter Lougheed Centre. (Submitted by Karim Manji)

Harton said that ranges from people living in trailers, to people living in homes with broken windows and no heat.

"We hear stories sometimes [of] people who live in RVs and they run out of propane during the night and it's really cold, and unfortunately they don't have sensation in their feet … and when they wake up in the morning, they have frostbite."

The change could mark a growing problem as Calgarians resort to unconventional living situations in an ever-tightening rental market — one that medical and poverty experts say needs to be tackled using preventative measures.

Last fall, CBC reported that campgrounds and RV parks near Calgary were facing increased demand from people struggling with rising rents. Meanwhile, Calgary's rental vacancy rate has reached a near-decade low as people continue to move to the province in droves.

According to the city's most recent housing needs assessment, nearly one-fifth of Calgary households could not afford their housing in 2021 — a number that's believed to be even higher today. More than 115,000 Calgarians are at high risk of homelessness.

In a province known for its volatile weather, Harton said it isn't easy knowing that people — housed and unhoused — suffer when temperatures dip below freezing.

"You feel like you're swimming in the ocean against a riptide. You want to help. Everybody wants to help. Everybody wants to do something. But what can you do, right?"

Frostbite diagnoses rise

According to data from Alberta Health Services, the number of frostbite diagnoses in Calgary hospitals has risen dramatically in recent years — though the information provided doesn't include the living conditions of those diagnosed.

The numbers provided by AHS are broken down by fiscal year, from April to March. This means each year of data includes one full winter season.

In the 2022-23 fiscal year, there were 740 visits for frostbite in Calgary ERs, urgent care centres and advanced ambulatory care centres, compared to 701 visits the year before that.

That's up from 396 visits in 2020-21, and 412 visits the year prior.

Utility costs play a role, says advocate

None of it surprises Sue Gwynn, chair of Poverty Talks!, a grassroots group of Calgarians dedicated to amplifying the voices of people living in poverty.

Gwynn said that amid the housing crisis, some people who are living under the poverty line have had to resort to lower-quality housing.

In some cases, people can barely afford to keep a roof over their heads — let alone afford to keep the heat running, she said.

Sue Gwynn is the chair of Poverty Talks!, a group of Calgarians living in poverty who aim to better inform policies through their lived experience. (CBC)

"It's the worst case scenario as far as rents being stupid high … and the cost of energy being driven through the roof and then we have a cold snap where you need to have not only power, but you also need to have gas running to your home," said Gwynn.

"And if you don't have one of those two things, your house is going to freeze and you're going to freeze along with it and it's just a terrible situation."

Prevention is key

For Gwynn, there's a simple short-term solution.

"We need to flood the city with winter gear, and it needs to come out of whomever's budget," she said.

Dr. Karim Manji, director of the Zivot Limb Preservation Centre, agrees. He said his team tries to offer socks to people in need, but it should be more widespread — including for those living in poor housing conditions.

"We really do rely on all the other stakeholders in our community to help. I think prevention here is key — to help early on and provide access to resources early on so that we don't have people suffer [from] frostbite," said Manji.

Longer-term, Gwynn said Calgarians living in poverty need better access to safe, warm housing.

"We need to take a proactive approach, [predicting] how many people are coming into our city ... you need to plan for those people and build housing accordingly."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News