Documentary 'Isky' Spotlights Ed Iskenderian, Now 102 Years Old

There's a scene in Cheyanne Kane's new documentary ISKY where the titular character, Ed "Isky" Iskenderian, is searching through the trunk of an old Cadillac for some cassette tapes he's sure he recorded and put there some 40 years previous. He finds them, and you can sense not just his joy, but the excitement of the film crew as he inserts one into a tape deck and the voice of Ed Winfield, Isky's mentor and one of the first performance cam-grinders of the automotive age, crackles into life, talking in depth on the importance of quench in a cylinder chamber.

It's a pretty amazing moment, the voice of someone who was born in 1901, at the dawn of the car, passing down his knowledge to someone who at the time of the recording, was still pretty young, but at the time of the listening was nearly 100, and at the time of our watching, 102.

Someday, someone is going to feel the same way about this documentary. Kane doesn't just tell Isky's story, which would rob the audience of the experience. Instead, she follows Isky and lets him tell stories: some about himself, some about Winfield, about famous racers and builder he worked with. In the end, it's the story of American hot rodding. The shots of Isky and his shop are intimate and loving. Isky's stories are hilarious and unexpected. Watching this film is like being in the room with Isky and his family. There's only one problem. The movie, produced by Kerry Ann Enright and Vigilants, doesn't currently have distribution, so you're going to have to take my word for it that it's fantastic. I encourage you to seek it out when it hits the film festivals.

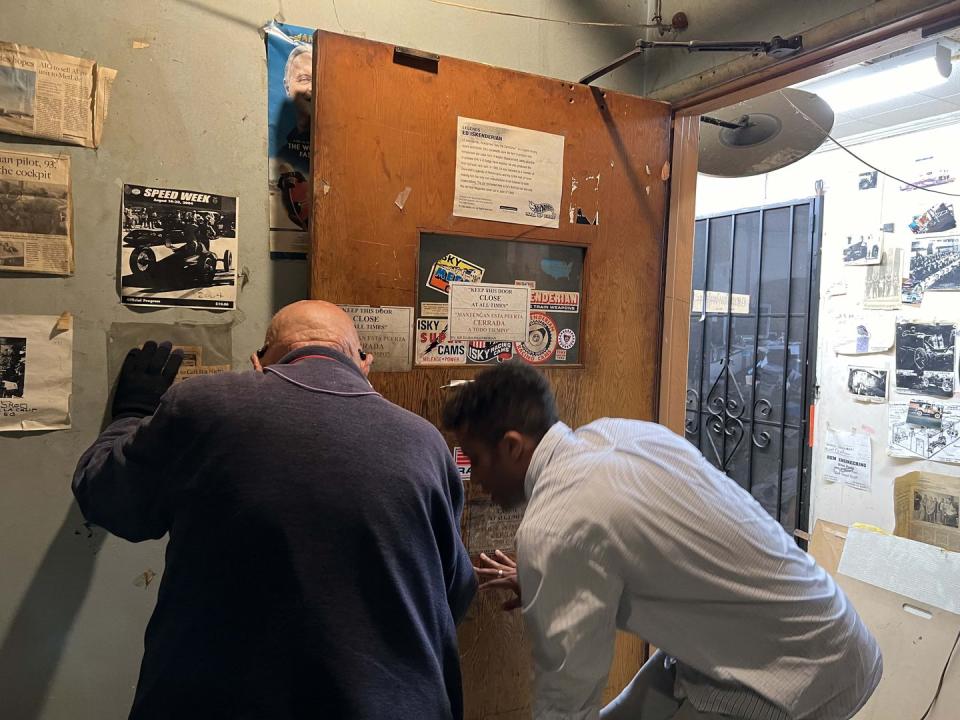

To tide you over with a little of that Isky magic, I went down to Isky Racing Cams in Gardena, California, to talk to Kane and Isky [who still likes to come in to work, despite having officially turned over the shop to his children] about the film, and it was immediately clear to me why Kane saw a movie in the man known as "The Camfather." Isky Racing Cams is romantic. It's softly lit, with ancient machines humming and overloaded shelves groaning in the background. More important, it's staffed by people, people who hand-grind, polish, and package the camshafts much the way Isky must have when he started the business back in 1947. Isky Cams has been in the Gardena building since the mid-Sixties, and the very walls have stories to tell, but not as many as Isky himself.

Isky sits across from me, wearing a blue button-down shirt the pockets of which are sagging with the weight of their contents. I can't imagine what's in them, as he's wearing all his important items like cellphone and car keys on lanyards around his neck. But then, I once saw him at a car show where he'd fixed his broken glasses with some lead weights on a piece of fishing line which he'd just happened to have with him, so his pockets could contain any number of things and I wouldn't be surprised. Somehow we've gotten off the topic of movie making and on to famous engine builders Isky has worked with over his many decades, and now he's got me playing a game where I just say a name and he tells me a story about that person.

"Ed Pink."

"Oh, I used to see him at the movie theater when I went to the show with my wife and kids. He was an usher there at the show. A kid."

"He's 92!"

"He wasn't then."

"Keith Black."

"Oh, [He often starts a story with a long drawn out Oh, a sound of delight in the tale he's about to tell.] I like to hear about when the experts make a mistake," he says. "One time, Edelbrock comes up with a new manifold. Aluminum, beautiful, six carburetors. They sent one to Keith Black, free, to get him to put it on one of his boats [Black started out with marine engines before moving over to building Top Fuel Hemis]. He doesn't do it. So the guys go get it back, and build their own boat, and they do good. They win. Then Keith Black calls up, I want the manifold back. He just didn't want to be the tester."

He had some other stories about Black, who didn't always use Isky cams in his builds, and therefore was more than once the subject of Isky's famous cartoon ads. These would come out in the rodding mags after a race, skewering the losing teams and Isky's competitor Howard Cams' camshafts. So intense was the rivalry that the back-and-forth during the '50s is known as "The Cam Wars."

The ads are worthwhile reading for anyone with an interest in automotive history, or looking for an example of brilliant marketing. They also give a great sense of Isky's sense of humor. Car racing is serious stuff, but Isky has always just had fun with it. He has fun with everything.

Kane's documentary begins when Isky is 98. "Don’t feel quite as peppy as I did at 97," he says, "But I'm hoping to make 100 because it will be easy figuring." The film alternates between Isky's early life as a budding hot rodder—"Model Ts were in every junkyard for $5. Maybe $10"—to the present day, as the still incredibly peppy Iskenderian attends races and signs autographs or spends time in the machine shop going over the finer points of cam cutting with his employees. All of whom, by the way, seem to absolutely adore him, both in the film and during my visit.

As we pass each work station, the machinist stops what he or she is doing and makes sure Isky has an arm to lean on if he wants it, and that nothing is on the floor to cause a stumble. "People learn from Mr. Isky," says one of the workers in the documentary, and it's clear that everyone in the shop enjoys the work and Isky's teaching. He's not related to everyone who works there, but they all treat him like a treasured grandfather.

Back when Isky was first getting interested in cars, Model Ts may have been plentiful but performance parts weren't so easy to find. Sure, you could stuff one of those neat flathead V-8s in place of the four-banger, and maybe finagle a better exhaust or a bigger carburetor, but the real magic for tuners in those early days was in camshafts, and aftermarket camshafts were hard to come by. In the '30s and early '40s, Ed Winfield and Clay Smith (who took over from Pete Bertrand) were really the only names in racing bumpsticks, and they cost about four times what the junkyard cars were going for. "Oh, that was the most expensive thing, the camshaft," says Isky. "That's what I liked about them. It was... what's the word? Exotic, little known, mysterious. That's it. Mysterious."

Isky likes to find exactly the right word for things. Perhaps it's the same mindset that he applied to buying a grinding machine in 1946 and turning it into a cam-grinder. It's still in the shop, by the way, with a fresh coat of paint on it.

With his new machine, Isky got to work figuring out exactly which curve and ramp on the cam lobes would be the right one to make power. Oh, actually, no, he says in the film that his first cam was a total fluke. He just made a guess at it, and since it was the only one he had, when the orders came in, he shipped it out. It just so happened that it turned out to be a great power boost for the stock-car racers who bought it.

All of Isky's stories are structured this way. Whether it's being inspired by the shape of an egg and ending up with a cam that massively bumped the output of a small-block Chevy, or having the foresight to create a fuel-saving cam profile in the '70s, he always ends his tales with a shrug and a laugh, like "Ha, who knew that would work?" He takes great joy in every detail, whether that's 60-year-old racing gossip or showing off the company's modern CNC machine.

Not everyone will have the pleasure that is a day in Isky's company, but his irrepressible spirit and industry-changing intelligence come across in Kane's documentary. We sure hope it doesn't end up in a Cadillac trunk for 40 years before viewers can enjoy it.

In the meantime, you can get a sense of the camaraderie and history at Isky Cams from this video by Alex Taylor (an Isky sponsored drag racer).

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News