‘Don’t you ever, stop being dandy’: Was the early Eighties the most colourful pop zeitgeist ever?

In the war-painted, Twitter-free days of 1981, ridicule was nothing to be scared of. Hence, as a fairy godmother played by Diana Dors waved her wand and transformed Stuart Goddard – aka swashbuckling pop heartthrob Adam Ant – from grimy servant boy to futuristic Prince Charming, his backing band the Ants gathered among the dames and courtiers in a set decked out as a Versailles ballroom to perform what would become an iconic dance for the nation’s growing legions of dandy pop warriors.

“I remember having to learn that valiant dance in about five seconds flat,” says Ants drummer and now renowned producer Chris “Merrick” Hughes, recalling the arms-above-heads march set to be mimicked in playground across the country. “It was all grand and big budget. It was Louis XIV with top buffoonery.”

The pouting pantomime of Adam and the Ants’ legendary “Prince Charming” video, the second single from their album of the same name released 40 years ago this week, came to epitomise the pomp and flamboyance that was flooding the pop charts at the dawn of the 1980s. Within weeks, The Human League’s “Don’t You Want Me” and Soft Cell’s Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret album, featuring their stark electronic take on Gloria Jones’s 1964 northern soul classic “Tainted Love”, would provide benchmark moments for the thriving synthpop scene. And already Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran, Ultravox, Heaven 17 and Visage – variously presented as Highland chieftains, 1940s spies, Parisian revolutionaries and sci-fi bellboys – had ensconced the burgeoning new romantic genre at the heart of the charts.

Adam and the Ants were never new romantics – they were rooted in post-punk guitar music, recently adorned with Burundi drumbeats. But their historical-futurist aesthetic of angular highwaymen, hussars, pirates and princes chimed with the prevailing pop zeitgeist: colour, escapism and wild costumery, in stark contrast to the drab, angry Seventies. Between them, from across the cultural landscape, all of these acts set the tone and timbre of the decade to come: flash, synthetic, gender-fluid, exotic, chimerical. The stuff of fantasy. The age of the unreal.

“The rationale that went along with it was that it was time for something flamboyant and not dull,” says Hughes. “Something which was escapist and vibrant and had some kind of social value. I guess people went, ‘yeah, I’ll align myself with that, that all feels good, that’s exciting, I can dress up.’ Adam liked the escapist sense of dressing up… he just thought it was liberating.”

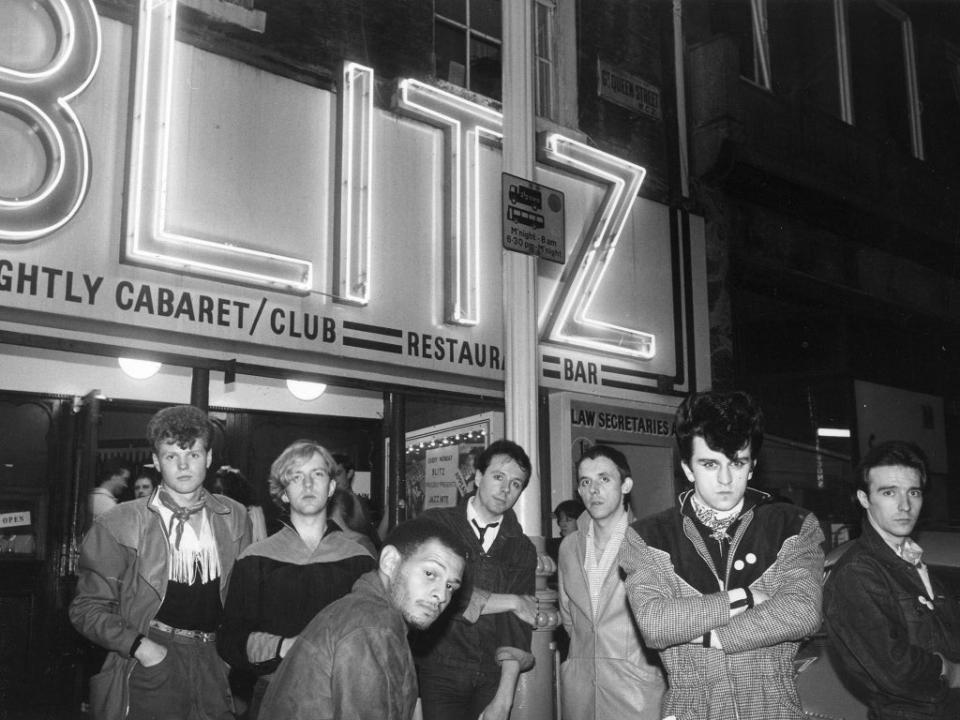

“Just for one day, we can be heroes,” says Rusty Egan, one-time drummer with Visage and co-founder of new romantic hub the Blitz club in Covent Garden in 1979 alongside charismatic Visage singer Steve Strange. We speak in a Charing Cross bar shortly after he presents a talk for an event entitled A Day of Romanticism, tracing the history of the Blitz from its origins as a Bowie and Roxy Music night at Billy’s bar beneath a Soho brothel to the epicentre of new romanticism. A place where art and fashion students, squat kids, King’s Road ace faces and soon-to-be-superstars would compete to out-fabulous each other every Tuesday night.

“Steve would show up dressed as a nun or something like that, and Boy George would show up going, ‘I’m dressed as a nun, you stole my image!’” he says. “Two nuns having a fight in the club. [‘Calling Your Name’ singer] Marilyn would roll up having a party for all his friends and they’d all bitch with each other. I loved them all.”

If the new romantic scene was an explosion of colour and creativity, by all accounts Britain needed it. “End of punk,” Egan says, “violence on the streets, skinheads, Labour losing it all, Tories coming in, dustbin men on strike, rail on strike, no money – it was a miserable and violent time.”

“You cast your mind back to the Seventies,” adds Ian Penman, executive producer of last year’s documentary on the club, Blitzed!, “there was the three-day week, there was rubbish on the streets, unemployment was massively high, there was this very depressing situation. Out of that came The Sex Pistols [and] this whole punk rock thing, but it was very negative, very ‘no future’. Rusty and others wanted beauty, romanticism, aspirational music… They wanted to dress up, they wanted to look special. It was pure escapism, getting away from your life on the dole queue and having no money and no job.”

New romanticism was also, Egan says, a reaction to punk. “Midge Ure and I had been in punk bands [they both played with The Sex Pistols’ Glen Matlock in his post-Pistols band Rich Kids before splitting off to form Visage in 1978] and been spat at, all the fighting and violence. We looked at each other in the dressing room after the last gigs and went, ‘It’s over mate, we’re not gonna endure that any more.’”

Looking to create a fresh seam of London nightlife beyond the punk gigs and disco clubs, he and Strange ran around the King’s Road recruiting “the coolest kids in town” to fill their initial weekly nights at Billy’s, essentially “a private party every week for three months”. When the club owner threatened to double the drink prices, they split; for several months Egan toured the major clubs of New York, Berlin and Paris, soaking up the vibe, taking stylistic notes and gathering records by bands no other DJ was playing: Kraftwerk, Switzerland’s Yello, Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra.

Relocating the night to the Blitz club, Egan would scare off the wine bar types with Edith Piaf, Grace Jones and Kraftwerk tracks before kicking off the party at eleven with Human League songs. “I wanted to transport you somewhere in the Blitz club, like film noir,” he explains. “It was 1940s ’Allo ’Allo, bottles of wine with candles in them, red and white tablecloths, ‘Your Country Needs You’ – it was like a set based on the blitz. Everybody dressed up and the music was electronic, futurist, with a bit of Jacques Brel and ‘La Vie En Rose’. You’d never been to a place like that… When you were in the Blitz club you could’ve been anywhere in the world. Visage, an English band with a French name? Yeah, and there’s another one called Depeche Mode.”

Meanwhile, Strange – dressed, according to journalist Robert Elms, “somewhere between a bellboy and a spaceman” – vetted potential entrants at the door, turning away anyone he deemed uninventively dressed. “The men dress outrageous, the women dress outrageous,” Strange (who died in 2015) says in archive footage used in Blitzed! “They’ve got to have a look to get through the door.”

“If you turned away the football boys, the pub boys, you ended up with the people you wanted,” Egan says. “We liked taboo. Extrovert gay people as in Boy George, Marilyn, the more the merrier. Models, photographers, hairdressers, creatives, you’re in the door. Rich kids and property developers, I don’t care how much money you’ve got, go somewhere else and buy your champagne. The exclusivity was to stop the homophobia. People wanted to beat you up. [It was] so we had somewhere to go. But it got a reputation that you can’t get in.”

It was not escapism, it was aspiration ... This was something you could get your teeth into, a world of possibilities

Mary McCaughey, editor of 'The Romantic View’

Amongst those refused entry to the Blitz was one Mick Jagger. “The place got so popular that the manager Brendan would say ‘no more’,” says Egan. “So Steve would be like ‘two more, two more, they’re my friends’. There was a bar up the road called the Zanzibar which closed at one and on a Tuesday night there was nothing open. We closed at three, so there was a mad onslaught of another 30 people wanting to get in. The manager says to Steve, ‘no more, I don’t care who it is.’ Steve milked it, but really he couldn’t have let him in anyway. According to people [who saw it] he didn’t give a f***.”

Inside this exclusive enclave, self-made style icons – pirates, debutantes, geisha punks, space Cossacks and kabuki sultans – took amphetamine and cast withering comment on the week’s parade. “It was the most exciting place I’d ever walked into,” Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp tells Blitzed!, recalling the Germanic beats and sense of Weimar decadence. “I remember [Spandau manager] Steve Dagger saying, ‘This is it, this is what we’ve been waiting for, this is our thing.’”

“It felt as though you were in a helter skelter with a bunch of paper dolls who changed outfits at the drop of a hat,” Midge Ure adds. But while the fashions of the Blitz Kids – often home-made or pieced together from daring items from shops such as PX in Covent Garden – might have been (karma) chameleonic, they weren’t for part-timers. “We lived it,” says Marilyn. “I used to get totally done up to walk to the end of the street to buy milk. Authentic… it wasn’t fancy dress.”

With their synthpop iciness (driven by the arrival of cheap synthesisers: “it was the advent of bands like Depeche Mode being able to buy something electronic,” says Egan) and eye-catching aesthetic, the new romantics of the Blitz felt like the sound and vision of the future. “We thought, ‘We’re gonna make the next decade about us and it’s gonna be different,’” Kemp tells the documentary. “It’s gonna be in colour.” But little could they know that by riding roughshod over gender binaries decades ahead of their time, they were laying the roots of future generations’ attitudes too.

“Everybody was playing games with their sexuality, with their clothing, with their identity,” Elms says in Blitzed! Boy George, who worked in the cloakroom (and admits to regularly going through punters’ pockets and handbags for valuables), hails the club as a crucible of resistance to mainstream norms.

“Sometimes being yourself is the most political act,” he argues. “Saying, ‘no, this is what I am, unapologetically. I’m queer and I’m not depressed about it’… You know very early on that you’re different and you’re developing in this weird vacuum and nobody wants to talk about what it is you are. Suddenly you walk into the Blitz and go, ‘My god, who knew there were so many others?’”

Then, one night mid-1980, the star-god fell to earth at the Blitz. David Bowie himself paid a visit, swept to the bar on the arm of Steve Strange before touring the club looking for intriguing figures to join his sci-fi Pierrot in the “Ashes to Ashes” video set to be filmed on an East Sussex beach the following day. “Everybody lost their cool,” says George, who was reportedly furious not to have been chosen.

The appearance of Strange and three other Blitz kids in the video (the most expensive ever filmed at the time) blew the lid on the new romantic scene. Spandau Ballet, the only band to play live at the Blitz, were signed to Chrysalis records at their very first show there. They were on Top of the Pops in tartan kilts performing their top five debut single “To Cut a Long Story Short” within months. Already primed for piston-hearted electropop by Gary Numan, audiences took easily to Visage (now fronted by Strange) and sent their second single “Fade to Grey” top 10 across Europe, enthralled by its continental mystique. “When you hear ‘Fade to Grey’ in a club in Munich and the girl’s speaking in French, they didn’t know where the record came from,” Egan says.

By the time Ultravox (now fronted by Ure) achieved a long-awaited breakthrough with “Vienna” and its spy noir video early in 1981, the industry had descended upon the scene en masse. Martin Degville (eventually of Sigue Sigue Sputnik) and Duran Duran were amongst the names discovered at like-minded clubs in Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham, while the Blitz proved to be a hive of Eighties-shaping talent. Besides Spandau, Visage and Ultravox, the likes of Heaven 17, Blue Rondo à la Turk, avant-garde new wavers Haysi Fantayzee, Marilyn, Culture Club and Sade would all emerge from its small coterie of new romantic frontrunners.

“Every f***ing person that went there had a band,” Egan laughs. “Art school boys who’d read a few books. [Ultravox’s original singer] John Foxx’s ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’, ‘(I Remember) Death in the Afternoon’ – these weren’t 1970s wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am pop songs. They were poetic and romantic and lyrically beautiful. Violins and pianos, not like punk’s ‘one-two-three-four!’”

Mary McCaughey, editor of The Romantic View, a publication which sets out to trace the lineage from earlier romantic movements to the new romantics, recalls the impact and appeal of seeing these early acts on her TV as a teenager in rural Northern Ireland. “It was not escapism, it was aspiration,” she says. “I never saw it as fantasy, I saw it as ‘this is who I am, a human being’. If you were 15 and your leaders at the time are people who are naked and on hunger strike [her MP was Bobby Sands] and then you see John Foxx on Top of the Pops, I didn’t think that looked like fantasy, that just seemed to me like a proper human being. Everything else was mad. This was something you could get your teeth into, a world of possibilities.”

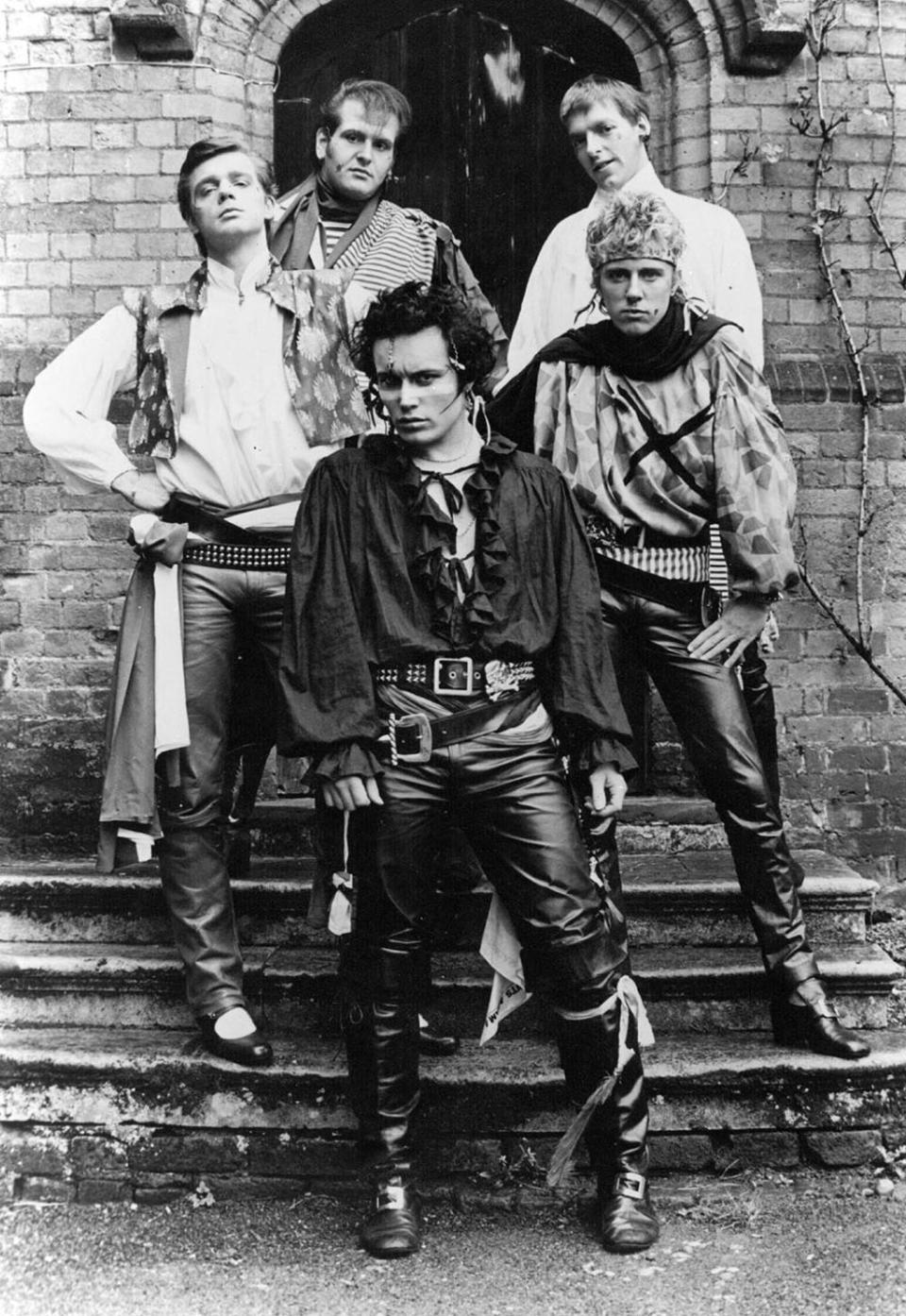

Meanwhile, across London at Vivienne Westwood’s Seditionaries boutique in King’s Road, the pirate dandy look was all the rage. Among the regulars taking note was post-punk Adam Ant. The crew who recorded his debut album Dirk Wears White Sox had been poached by manager Malcolm McLaren to form rival act Bow Wow Wow; now he was researching historical fashions such as tribal face paint and hussar outfits as he worked up a look for his new band of Ants.

Hughes was amongst his new recruits, selected for his production skills (post-Ants, he’d enjoy a celebrated career as producer for the likes of Tears for Fears and Paul McCartney) and knowledge of the Burundi warrior rhythms Goddard wanted to weave into punk shanty melodies on his second album, 1980’s Kings of the Wild Frontier.

“I was very aware of the fact that Adam had a massive engine,” Hughes recalls. “He was unbelievably fashion aware. But I see him as someone who set a trend, he never seemed to align himself to one or follow anyone else. He was very, very much his own man… His level of competitiveness, wanting to be huge… We were rehearsing somewhere near Islington and we used to meet at this café. He said, ‘sorry you’ve got to set your own drums up but six months from now we’ll be household names, we’ll walk offstage straight into cars to get back to the hotel.’ He had an unbelievable sense of being successful, Top of the Pops and a very, very commercial mindset.”

In “Kings of the Wild Frontier” and “Antmusic” he also had the tunes to match, while his slash of white warpaint and year zero mission statement – “unplug the jukebox and do us all a favour/ That music’s lost its taste so try another flavour” – instantly epitomised a scene the Ants were only peripherally associated with. They were aware of the Blitz scene but never took carriages there looking for a duel. “Adam never said to us, ‘come on, let’s go down and put in an appearance, wear our regalia and be amazing and show them how it’s done,’” says Hughes. “It’s the stuff of cartoons, that is!”

Adam and the Ants swiftly swept their Blitz contemporaries aside. Three singles from Kings of the Wild Frontier went Top Five and the album topped the charts. For Hughes, the breakthrough success was a kaleidoscopic whirlwind. “It was fun, very exciting: one minute we’re doing this the next minute we’re flying over to Sweden or wherever it was. It got very chaotic, we forgot which day Friday was. I wouldn’t go down Putney High Street in my Ants gear but, I enjoyed us all getting ready for a gig in a hotel somewhere, meeting up in the lobby, turning people’s heads and then piling into cars and getting to the gig.”

When it came to recording highwayman romp “Stand and Deliver” in 1981, with its galloping horse noises and video full of tribal Dick Turpins, banquets and gallows escapes, however, The Ants were teetering on the edge of Regency panto pop. “One of the successes of the Ants was that that they were ridiculously uncool, corny, camp, funny, serious and cool,” says Hughes. “It was a fairly unique blend.”

Hitting No 1, the single tipped new romanticism over an edge. Following the theme, the “Prince Charming” video went full King’s Road Cinderella, a level of costumed opulence which the new romantics couldn’t credibly top. As such, it marked the pinnacle and climax of the genre’s flashbulb dazzle.

“Past that point Duran Duran looked smart,” says Hughes, “they looked like Italian-suited lads. It was flamboyant and had a certain class, but it was much more of the clubs, much more reasonable fashionwear, whereas the Ants stuff was pantomime by that point. The Duranies were looking more and more popstar-ish and slick. You could walk down the road looking like that and it’d look pretty flash, whereas walking round in Prince Charming stuff would look slightly odder.”

By late 1981, the new romantics had refreshed, rebooted and Technicolored British culture for the new decade, making pop stardom seem fantastical again, in Bowie’s image. But as the hits piled up and the money rolled in, actual extravagance replaced the Blitz kids’ art school impressions of it. Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet embraced the international playboy lifestyle and aesthetic: Med fashions, yachts, flying down to Rio. It was a lucrative and hugely successful approach, even seeing a new British invasion break America, where the mirage of moneyed success is worshipped to this day. But it was one which seemed exposed as shallow and overblown by Band Aid in 1984, and floundered thereafter.

Meanwhile, with Visage struggling to follow up “Fade to Grey”, Egan and Strange left the Blitz to launch Club for Heroes, first in Baker Street then at the Camden Palace, drawing the likes of Grace Jones, Wham!, The Eurythmics, Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Madonna. Ultimately, Egan claims, drugs “killed us all, although at the time it was a f***ing lot of fun. Acid, ecstasy, MDMA… I loved everyone”.

The pressures of success did for The Ants too. With the Prince Charming album scorned by the press as too much style over substance, Goddard dismissed the band besides Hughes and guitarist and co-writer Marco Pirroni and returned in 1982 dressed as a toned-down gunslinger for horn-blasted jive hit “Goody Two Shoes”.

“There came a point where I think Adam was exhausted,” says Hughes. “The level of success, which was pretty quick, and the demands on him were pretty intense. I think he felt the pressure to come up with another album, come up with another tour, another look, and I think he just wanted to do it on his own… It was a short thing, which supernova’d and burnt out and then he went on to do his own thing.”

New romanticism fell from fashion by the late-1980s and seemed a warning from history during the Britpop knees-up. But as synthetic textures revived over the past 20 years, its influence had become inescapably embedded at the very core of modern music, from The Killers to Perfume Genius, Daft Punk to Kanye West, LCD Soundsystem to Lady Gaga.

The Blitz vision of the future undoubtedly came true, to the point where, for the past decade or so, music seems to have agreed that the early Eighties was the ultimate sonic endpoint upon which it cannot improve. But McCaughey argues that this isn’t merely down to cyclical revivalism.

“That decay that was there with the post-war period, what we’re seeing now is the same issues coming to the fore, decay,” she says. “Romanticism never really goes away. Karl Marx said, ‘as long as you have capitalism you will always have romanticism.’ It might be quite under the surface, but you’ll always have romanticism as a reaction to the emptiness of capitalism.”

It’s music, then, that might never lose its taste. And thankfully, it has infinite flavours.

Read More

Gary Kemp: ‘My younger self is trapped in a bell jar’

Cocaine, no sleep and deep soul: The story of David Bowie’s Young Americans

Sean Paul interview: ‘Weed from legal dispensaries tastes like cardboard’

The 30 greatest album covers, ranked

The War on Drugs: ‘Springsteen gets a kick out of my son being named Bruce’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News