Dorothy Bohm, photographer who fled the Nazis and became celebrated for the joy and serenity in her work – obituary

Dorothy Bohm, who has died aged 98, was one of the last doyennes of post-war British photography; in a career spanning eight decades, she befriended photographers from Bill Brandt to Martin Parr, helped to develop the Photographers’ Gallery in London and created a large body of humanistic work characterised by a peripatetic lifestyle and an empathetic eye for women and children at work and play.

Her photographs – often full of joy and serenity – belied a life scarred by tragedy. As a Jewish teenager in East Prussia during the 1930s, she had grown up in the shadow of the Nazi threat. Eventually, for safety, she was sent to join her brother in Britain. “My father was one of those who believed in anything new and so in the 1930s he was using a Leica,” she recalled in an interview with the Telegraph. “And when I was shipped off to England because Hitler had come, and life had become impossible, saying goodbye to me he took off his Leica and gave it to me. It was strange. He said: ‘It might be useful to you’. ”

She did not see her parents or younger sister again for two decades: they were taken by the Soviets and her father incarcerated in a labour camp in Siberia.

Her father’s comment regarding his Leica proved remarkably prescient. At the end of the war, Dorothy opened a portrait studio in Manchester and, from the late 1940s, began shooting street photography. In this she was aided by the travelling work of her husband, Louis, a pharmaceuticals executive.

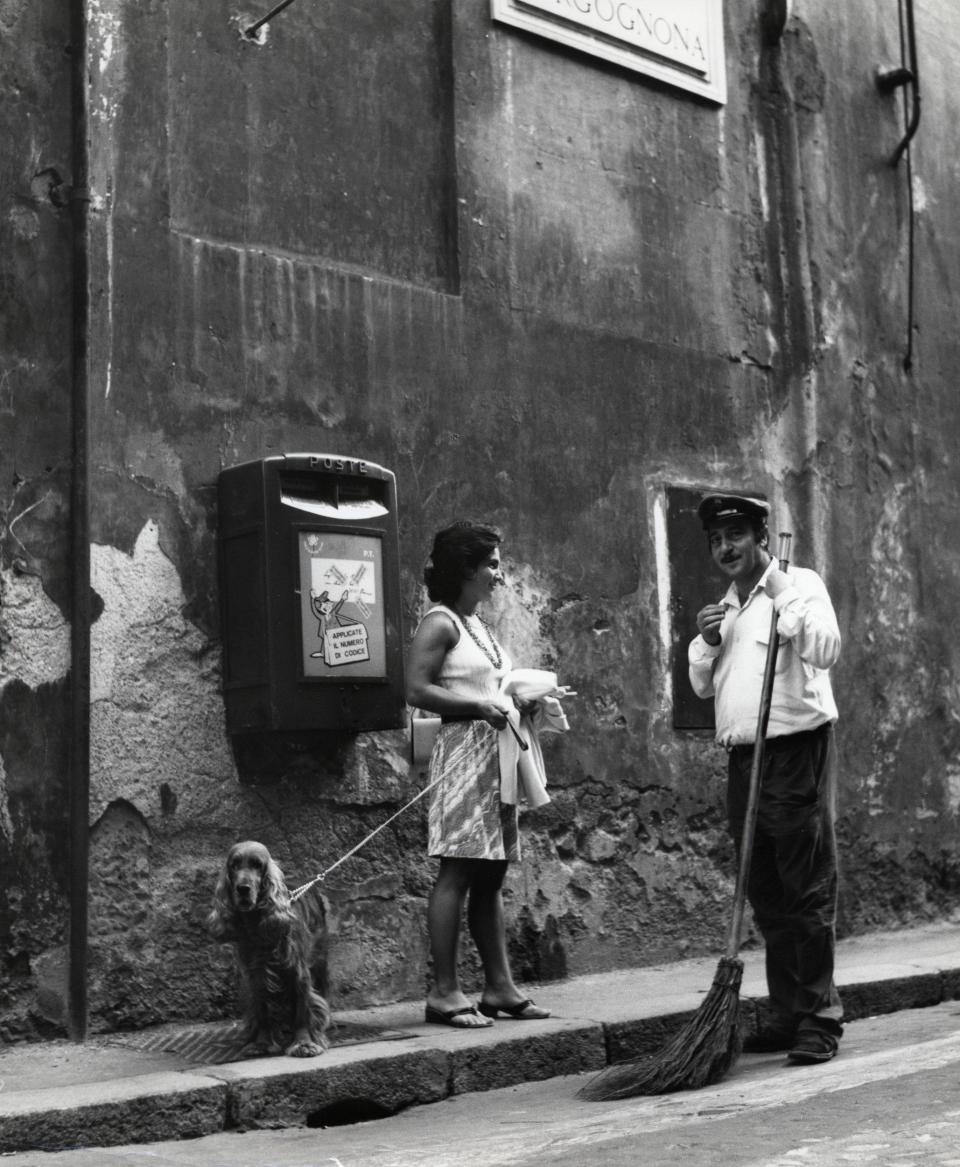

Her photographs captured everyday interludes: women at fruit and flower stalls in Switzerland and Belgium, resting shoppers in New York and Cordoba, browsers on Petticoat Lane Market in London and concierges on a break in the Marais. The men in her pictures were largely benign figures: punters at Goodwood, painters in Montmartre.

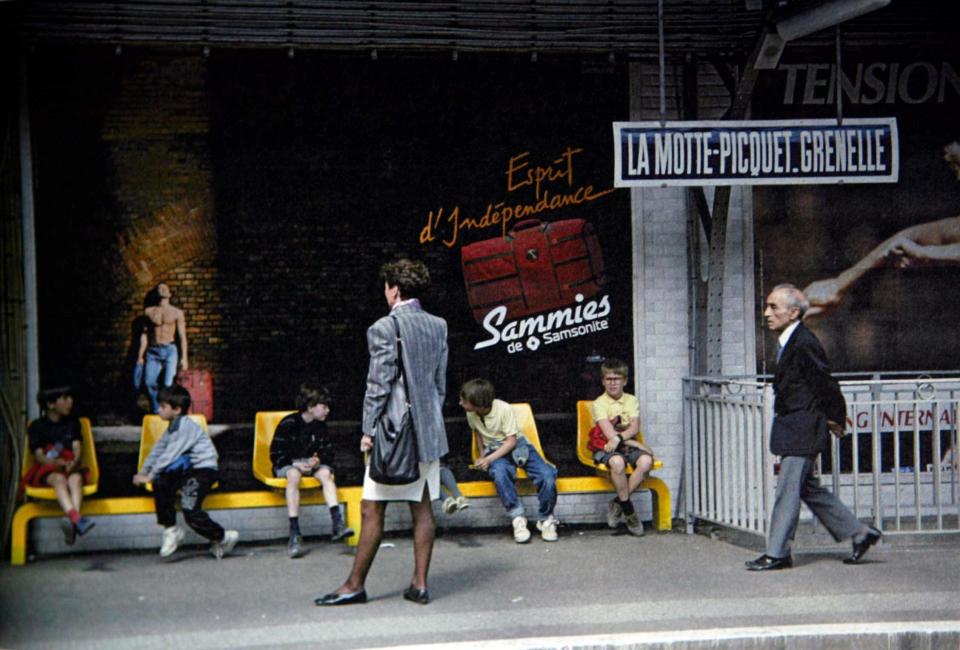

“I think of women as the most natural subjects for me,” she once observed. Children, too, were relaxed in her presence, providing an array of engaging figures: a series of shots of children in Paris taken in the mid-1950s depict an alternative knee-high life of mischief, while one of her later colour shots from the 1980s cleverly echoes a pair of baby elephants with two schoolgirls on a visit to the Zoo de Vincennes.

Such happiness seemed at odds with her family story. In her later years, Dorothy Bohm reflected that England had been her salvation. “It’s the best country, I can tell you that, and I’ve lived in a number of them,” she noted, “Why? Because of the people.”

Photography, she maintained, became a coping mechanism. “I am temperamentally suited to being a photographer. You can only make a picture of something that exists, right? And for me that was quite important. I wanted to capture time. My background completely disappeared.”

She was born Dorothea Israelit on June 22 1924 in Königsberg, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad in Russia) into an affluent Jewish family of Lithuanian industrialists. “I was a dumpy little girl,” she recalled. “I hated being photographed.”

As the situation deteriorated under Nazi rule, the family moved to Lithuania, first to Memel and then to Šiauliai, before Dorothy left for England, where her brother Igor was studying at Manchester. Aged 15, she arrived at a boarding school in Ditchling, East Sussex, where she learnt English in a year. After leaving school, an apprenticeship with a photographic studio on Baker Street was cut short by the Blitz and she relocated to Manchester.

She studied photography at Manchester College of Technology, where she met her future husband Louis Bohm, a young Polish Jew studying chemistry (his mother and sister both died in the Warsaw Ghetto). As a Lithuanian, Dorothy was considered a “friendly alien” and during the war she gave Ministry of Information talks, drawing on her personal experiences, about the crimes of Nazi Germany.

In 1945 she married Louis, who encouraged his wife’s photography. Following a period at the studio of Samuel Cooper, learning printing and retouching images, she opened her own business, Studio Alexander, on Market Street in Manchester. Taking formal portraits taught her how to engage with sitters and search out the beauty in faces. In 1947, a trip to the bohemian community at Ascona on Lake Maggiore launched her into en plein air photography.

In the early 1950s Dorothy and Louis settled in London, where they brought up their two daughters. Louis’s work, however, brought extensive travel, allowing Dorothy to shoot in locations that were exotic for the time, such as Mexico and South Africa.

In 1960, having received word through the Red Cross that her parents were safe and living in Riga, she travelled to meet them in Russia. While there, she was trailed by security services. “I took two pictures in Moscow’s GUM department store, which in Soviet times wasn’t much. I believe it is elegant now,” she recalled in 2016. “I was slightly uncomfortable taking them. I did not know if I’d be stopped. We knew we were being watched, so I was taking a risk.”

In 1963, her parents were granted permission to live in London.

She had her first solo show in 1969 at the ICA, where her exhibition, “People at Peace”, was juxtaposed with “The Destruction Business”, a selection of Don McCullin’s war photography. Her first photobook, A World Observed, was published the following year.

Her photographic output decreased during the 1970s as she helped to build the reputation of the Photographers’ Gallery, which opened in 1971 in a former Lyons Tea Room in Covent Garden. As an associate director for 15 years, she worked on exhibitions of veteran snappers and emerging talents such as Sarah Moon and Colin Jones.

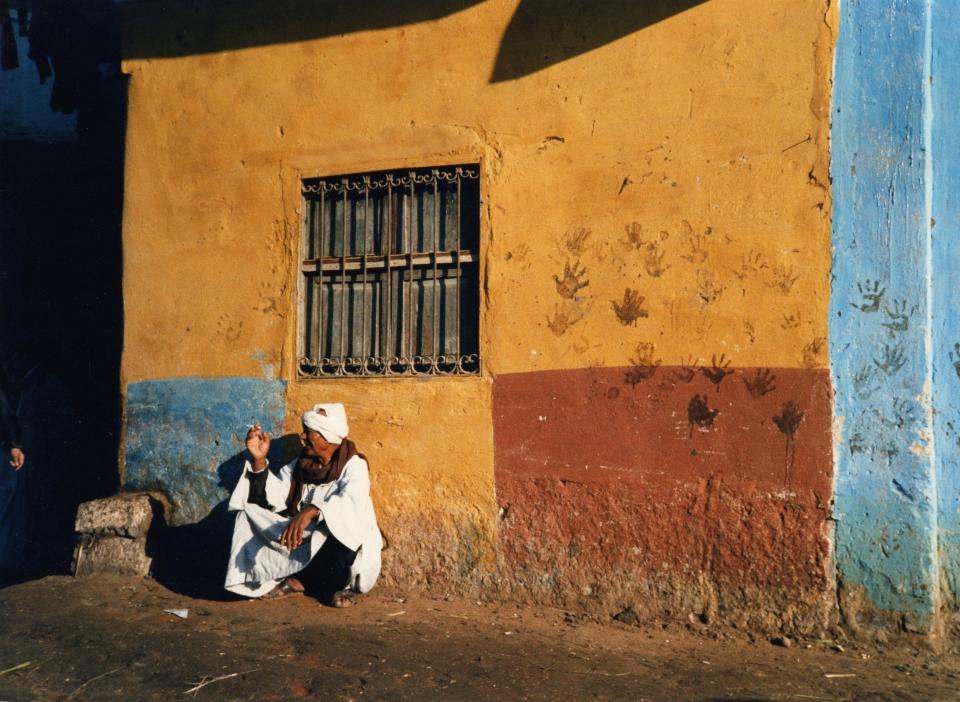

From the mid-1980s, Dorothy Bohm worked primarily in colour, embracing collage-like compositions of torn posters and pavement furniture, and surreal reflections in shop windows and puddles. In these, she exhibited a particular fondness for a strong red.

The Hungarian photographer André Kertész, a friend and inspiration to Dorothy, was an admirer of her vibrant Polaroids. She also bonded with Martin Parr: “When I photograph the English, I photograph the way I see them, whereas he has that sense of humour,” observed Dorothy. “And he is as right as I am right.” She got on less well with others: Cecil Beaton, she said, “did not know how to cope with the photography. Somebody else had to help him with the shutter.”

The death of Louis in 1994 caused Dorothy to consider giving up the camera. “And then I thought he’d be ashamed of me,” she noted, “and I started to photograph again.”

Her photobooks include Egypt (1989), Venice (1992), Sixties London (1996), Walls and Windows: Colour Photography (1998), A World Observed, 1940–2010 (2010) and About Women (2016). She exhibited regularly in the latter half of her life, with numerous shows in London at the Photographers’ Gallery, Ben Uri Gallery and Focus Gallery, as well as retrospectives at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Two television documentaries – Dorothy Bohm: Photographer (1980) and Seeing Daylight: The Photography of Dorothy Bohm (2018) – were made about her life and work.

She photographed well into her 90s, often around her neighbourhood in Hampstead, continuing to capture quiet, dignified moments. A photograph, she said, “makes transience less painful”.

Dorothy had two daughters, one of whom, Monica Bohm-Duchen, is an art historian.

Dorothy Bohm, born June 22 1924, died March 15 2023

Yahoo News

Yahoo News