How A Dream To Bring Back Wild Buffalo Is Slowly Decolonizing Tribal Land

WIND RIVER INDIAN RESERVATION — On a sunny August day, Jason Baldes drove a mud-caked quad with a drink holder overflowing with matted buffalo fur toward the wild herd he has overseen since 2016. The day before, the Eastern Shoshone had killed one of the bulls, and the smell of warm blood and fresh meat still hung in the air. As we bounced over dirt clods, we passed the esophagus and pair of lungs that Baldes had left as a gift to the coyotes.

Every harvest from the growing herd marks a major victory for the Eastern Shoshone, whose untranslated name, Gweechoondeka, literally means “buffalo eaters.” But this one was special. For the first time in 139 years, the annual sun dance ceremony, a multiday ritual, would include buffalo meat — a key ingredient that had gone missing since European settlers all but wiped the animals off the map in the late 19th century.

“You can’t have a sun dance without buffalo,” Baldes said. “You can’t use a cow.”

The buffalo appeared as we approached an interior fence nearing the western end of the property. Their patchy summer coats, shed almost to the skin to keep them from baking under the summer sun, gave them a half-naked look. A few bulls grunted, gurgled and chased one another in light sprints — signs that breeding season had arrived. Most either lay bedded in the pasture or ambled along feeding.

The field, speckled with yellow-flowering pineapple weed, wasn’t an ideal feeding spot for bison, who prefer grass. But for millennia the spaded hooves, concentrated grazing and wallowing of wild buffalo had shaped the ecosystem of the high plains. Baldes wanted to see whether simply setting the animals loose on the field would limit the invasives that had flourished over years of fallowing before seeding it with something else.

“Buffalo are ecologically extinct,” Baldes said. “But they’re a keystone species — ecosystem engineers. They’re the best land managers if you allow them to do it.”

The land that interested Baldes most, however, stretched beyond the fence. A few hundred yards away stood a white house behind a pasture and a towering irrigation system. Further out, a stand of trees marked the boundary for another neighboring piece of private land. Baldes plans to snatch up as many tracts like those as he can.

“If I had $20 million right now, we could lock up 10,000 acres of fee land on the river — if not more,” Baldes said. “There’s a lot of implications to getting these lands back.”

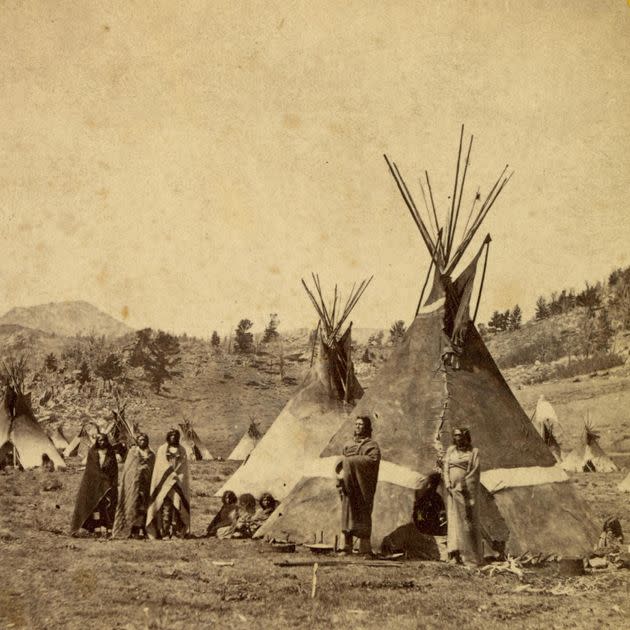

Wild buffalo once infused virtually every aspect of life for plains tribes like the Eastern Shoshone. The meat provided their most plentiful food and most reliable source of fat. They built their lodges from buffalo hides, used the bones for their utensils and dried the bladders for water vessels. Many buffalo-hunting tribes lived nomadic lives dictated by the animals’ seasonal migrations; buffalo defined what it meant to be “home.”

For the last three decades, a coalition of dozens of tribes whose lives once revolved around wild bison have spearheaded a unique movement to restore the all-but-extinct animals. (The words “buffalo” and “bison” refer to the same animal, known by the scientific name Bison bison.) Led by the InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC), where Baldes serves as vice president, the effort has so far shepherded about 25,000 wild bison to more than 65 herds on tribal land. That figure likely accounts for well over half of conservation bison left in North America, making Native people the most important guardians of wild buffalo genetics.

But getting the animals is only half the battle. Virtually all reservations lack the land base that wild bison demand — a legacy of federal policies that have pilfered tribal holdings for a century and a half. Much of the land that tribes retained is managed to raise beef cattle rather than protect wildlife.

Baldes has crafted a unique solution. With money raised from the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative, a nonprofit he founded at the beginning of the year, Baldes is systematically buying up privatized land that the Wind River Indian Reservation lost more than a century ago, with the goal of reenrolling it as tribal land. The sole condition is that the parcels remain designated as wildlife habitat for buffalo.

The nonprofit emerged out of a strategy that Baldes has used for years, allowing Eastern Shoshone buffalo pastures to mushroom from a 300-acre pen seven years ago to more than 2,000 acres today. This summer, Baldes scored his biggest win yet, when the reservation’s two business councils jointly voted to retire a 17,000-acre tract of tribal land from cattle grazing and turn it into wildlife habitat for bison.

Once fenced, a project that the nonprofit will have to raise $2 million to accomplish, the new land will join the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho’s wild buffalo herds for the first time, placing the Wind River Indian Reservation’s buffalo enclosure among the largest found on tribal land nationwide.

“Our goal is the same as Jason’s: Get as much land as possible for our buffalo,” said Dennis O’Neill, who manages the Northern Arapaho tribe’s buffalo enclosure.

For the plains tribes that lived alongside wild bison for millennia, the animals’ return marks a multidimensional triumph.

The meat, leaner than beef with a healthier balance of omega-3 fatty acids, promises to help assuage the high rates of diabetes that have plagued Wind River since the introduction of processed foods. The herd offers a unique opportunity to study the impacts of returning bison to their historic landscape. Ceremonies and rites of passage preserved using deer or elk as substitutes can resume in their true form.

Reacquiring the land makes it all possible. Doing so at zero cost to cash-strapped tribal governments with a minimum of political conflict in a region dominated by cattle ranching is pretty much unheard of, but Baldes has managed to do just that. Some neighbors, eager to help, are waiting to sell their properties until the nonprofit can come up with the money.

“We’re not in a giant rush,” said neighbor George Hellyer. “We really don’t have any desire to be in the middle of something that’s actually working.”

Baldes is only getting started. Rearranging the tangle of private and tribal land has become a high-stakes puzzle that promises to create one of the most expansive migration corridors for wild bison, while striking directly at the colonial legacy that wiped them off the landscape in the first place.

“I want to see thousands of buffalo and tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of acres protected for wildlife,” Baldes said. “What we do here on the reservation could set precedent for what buffalo restoration can look like.”

‘Trespassers On Our Own Land’

Wind River Indian Reservation boasts abundant natural beauty and a strong conservation history. Flanked on two sides by mountain ranges, the heart of the reservation runs along a vast stretch of high desert sagebrush steppe, dotted with herds of pronghorn antelope. Nearly three decades before Congress passed the Wilderness Act of 1964, the reservation elected to shield a 187,000-acrechunk of the Wind River Mountains from development in perpetuity. Its trout fisheries and mountain vistas attract adventurers from across the country.

But the reservation is a tiny fraction of its former self, carved up by the same processes that left the overwhelming majority of tribal holdings checkerboarded with private lands held by outsiders.

The Eastern Shoshone’s original reservation, envisioned in the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1863, spanned nearly 45 million acres across an expanse that included parts of today’s Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Utah and Colorado. The second Fort Bridger treaty, signed five years later, shrank the reservation to just 2.75 million acres and moved it to its current location along the Wind River valley in Wyoming.

The tribe lost another third of that land with the Brunot Cession of 1874, which handed the southern chunk of the reservation to white settlers who discovered gold there. Four years later, the U.S. Army ushered the Northern Arapaho — historic enemies of the Eastern Shoshone — onto Wind River Indian Reservation in what they described at the time as a temporary arrangement. The two tribes still share the reservation today.

A few years later, they began to lose control of the land that remained within the reservation itself. Eager to transform tribes of semi-nomadic hunters into farmers and ranchers, Congress passed the Dawes Act in 1887, imposing a land-tenure system called “allotment.”

Modeled on the Homestead Act, the law doled out blocks of roughly 160 acres for farmers and double that for ranchers from tribes’ communal holdings. After exhausting the supply of tribal allottees, the law opened up tribal lands to white homesteaders. Many allottees would go on to sell their holdings under duress, turning them into privatized “fee lands.” The nationwide tribal land base dwindled by about two-thirds due to allotment.

“We became trespassers on our own land,” Baldes said.

Wind River fared better than many, but lost massive chunks of the river valley, which became cattle ranches. The communal lands the tribes managed to retain mostly converted to cattle pastures too, at the direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs — the same agency that spent much of its history imposing “assimilation” policies that included drafting children into boarding schools, forbidding the use of tribal languages, and criminalizing Indigenous religion.

Baldes grew up with deep insight into both the reservation’s unique conservation heritage and its political battles.

As a biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Baldes’ father, Dick, was among the few people employed to steward wild lands on behalf of the federal government on the reservation where he was enrolled as a tribal member. Most of the tribal wilderness area remained unsurveyed and poorly managed by the time Dick Baldes took his position; his predecessor’s main contribution was dumping rainbow and cutthroat trout into several backcountry glacial lakes,destroying a golden trout fishery in the process.

Baldes’ father started bringing him along on backcountry work trips when he was a young child. Living out of horse camps for up to a month at a time, Jason Baldes learned to hunt, fish and identify wild plants around the same time he learned how to read.

“That’s how Native people always were,” Baldes said. “Our health and wealth was in the biodiversity of plants and animals.”

He felt the absence of buffalo from an early age. On hunting and fishing trips into the Owl Creek mountains on the reservation’s northern border, Dick Baldes pointed out the depressions left by wallowing bison before their extirpation in the 1880s. Occasionally they found buffalo skulls or bones in the washouts.

Baldes’ father’s work exposed him to what successful conservation can look like. The era of unregulated hunting had left the reservation bereft of pronghorn, despite boasting perfect habitat for them. Bighorn sheep, a species that once numbered around 2 million but now struggles across its range with diseases brought by European livestock, had also been wiped out.

Dick Baldes enlisted schoolchildren, including his son, to help trap pronghorn for relocation with drop nets after baiting them with hay and apples. Jason Baldes was there when his father’s team released the first bighorn sheep off a trailer into Wind River Canyon.

Today, herds of pronghorn are a common sight across the plains running through the middle of the reservation. Three bighorn mounts adorn the living room wall of Dick Baldes’ home on the foothills of the Wind River mountains. Dick shot two of them, and Jason shot the third. In the Lower 48, hunters can consider themselves lucky if they get the opportunity to hunt a wild sheep, successfully or not, once in a lifetime.

Dick Baldes’ job also gave his son a front-row seat to the reservation’s bitter conflict with the state of Wyoming over water.

The land that outsiders took from the reservation through cession, sale or allotment wasn’t worth much without water. Legally murky water claims piled up over the years, at times spurring still more land loss.

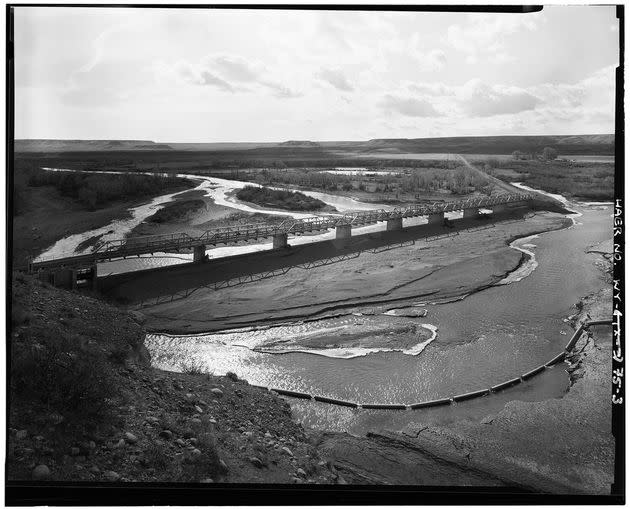

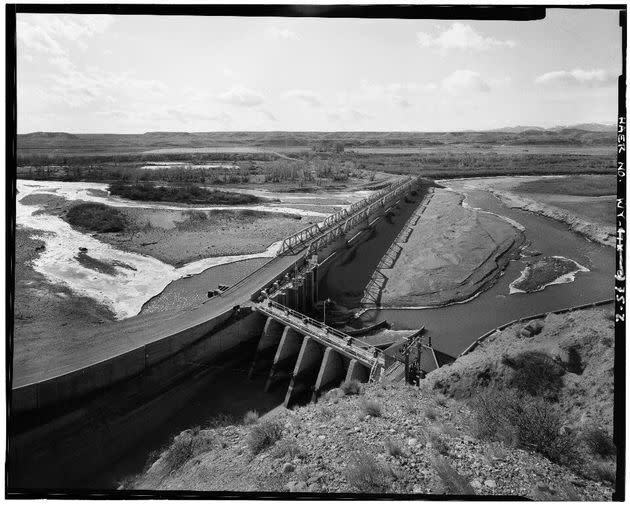

One of the most obvious reminders of that legacy lies a few miles up the road from the Eastern Shoshone buffalo enclosure, where a rusted metal bridge passes over the top of Wind River. Below it, the century-old Diversion Dam redirects part of the Wind’s flow into a concrete canal that streams off toward the north. It’s easy to distinguish the fee lands irrigated by the canal from satellite imagery — in an otherwise arid region, they appear bright green.

What’s left of the stretch of the Wind River flowing east from Diversion Dam to the town of Riverton stagnates in the summer months. The drawdowns for irrigation combine with evaporation to lower the water level and heat up what remains, making it impossible for cold-water fish like trout and lingto survive. Combatting the Wind’s depletion became one of the great passions of Dick Baldes’ career.

His tenure at the Fish and Wildlife Service overlapped with a decadeslong legal reckoning between the tribes and the state of Wyoming over control of the region’s water.

The state courts upheld the tribes’ water rights in 1989, awarding them 500,000 acre-feet based on their treaty with the federal government, according to “Public Waters: Lessons from Wyoming for the American West,” by journalist Anne MacKinnon. Wind River’s Tribal Water Office decided to apply nearly half of its water rights to recharge groundwater and keep the Wind flowing full enough to keep its cold-water fish alive through the summer.

After the state refused to enforce the tribes’ decision, a district court took the unprecedented step of handing administration of the stretch of the Wind River flowing through the reservation’s historic boundaries to the tribes.

“The non-Indian were going bonkers — ‘Ah, the Indians are acting up, the Indians are going to destroy us, the Indians are going to burn us out,’” said Wes Martel, a former member of the Eastern Shoshone business council. “But at the end of that year, we had our in-stream flow and they had banner crops on the reclamation project. That showed us that in-stream flow and agriculture and the reclamation project can survive together. ’”

But in 1992, when Jason Baldes was in middle school, the Wyoming Supreme Court overturned the decision, handing victory back to the state. The ruling required the tribes to follow state law if they wanted to use their water rights for anything other than agriculture and gave the job of regulating the Wind River back to the Wyoming State Engineer. The court declined to protect the tribes’ groundwater rights at all.

“The water rights case always stuck with me,” Baldes said. “Like, man — how can they screw us over that bad?”

Opening Doors For Buffalo Restoration

The ruling dealt a heavy blow to Dick Baldes, who developed ulcers and increasingly butted heads with higher-ups at work whom he viewed as unsupportive of the tribes’ water claims. He was suspended without pay four times — three of them over fights about water, and the fourth after tangling with a regional director over the agency’s decision to shut down field offices on nearby reservations.

“It’s still upsetting to me,” he said. “That battle is going to continue until we get groundwater back and we get in-stream flows whenever we want them.”

The case also catalyzed Jason Baldes’ desire to find a calling, though he wasn’t sure what.

“I just kind of wanted to battle against colonization,” he said. “There’s been too many atrocities for that to just happen and have no repercussions.”

He played outside linebacker through high school, enjoying a light load of classes with afternoons off, but struggled to find an interest that matched his budding ambition. Noting his restlessness, his father suggested traveling to East Africa for a few months, where a friend of the family had relocated.

The trip became a pivotal moment. Dick traveled with his son for the first couple of weeks, where the two visited the Serengeti to watch the start of the wildebeest migration. The sight left a major impression on the 18-year-old Jason Baldes, who panned around in circles filming the tens of thousands of animals with a monopod-mounted video camera.

“That was pretty incredible,” Baldes said. “But more unfathomable to me was that it was less than 5% of the buffalo that were here less than 200 years ago. When I returned home, I had a newfound appreciation for buffalo, for my home, for my community, where I’m from. And I thought, if I were to focus my education on this, it might open some doors for buffalo restoration.”

It was a fortunate time to make that decision. The organization that would become the InterTribal Buffalo Council had been founded a few years earlier, in 1992, sparking the modern tribal restoration movement. But it gained real steam in 1997, when Montana officials slaughtered hundreds of buffalo outside Yellowstone National Park — the budding restoration movement’s most important source population.

Yellowstone’s wild buffalo descend from a group of two dozen stragglers that escaped the market hunting era. Congress initially created the park in part to protect the animals from poachers, revoking tribes’ historical right to hunt, fish, forage and camp there in the process. Over time, the park’s buffalo population rebounded, topping 3,000 by the late 1990s.

But even Yellowstone, at 2.2 million acres, isn’t big enough to hold the bison. When snow piles up during harsh winters, bison descend into the valleys looking for feed. Because they are widely infected with brucellosis, a contagious disease that causes abortion and low birth weight, the state of Montana has taken a strict stand against allowing them to freely wander into the state’s ranch lands, where they threaten to spread the disease to cattle.

Culling migrating bison was common for decades before the winter of 1997. But two years before, the state of Montana put bison management into the hands of the Department of Livestock, rather than wildlife officials. The unprecedented scale and waste of the killing that resulted brought national media scrutiny, public protests and a major lawsuit that changed buffalo management. The plan adopted in 2000, which is still in effect today, gave the ITBC a role in managing Yellowstone buffalo, and laid the basis for a new system to transfer the park’s bison to reservations after a quarantine period.

Contention over the future of Yellowstone bison drove widespread interest in restoration. The nonprofit American Prairie Foundation started buying up private land for wild bison in 2001, and today owns 126,101 acres, and leases another 336,702 acres of federal and state public land. And around that time, the Wildlife Conservation Society had begun mapping out areas across the country with ideal bison habitat. One of the best they found was Wind River.

Despite allotment, the reservation retained an unusually high percentage of its land, especially at higher elevations. WCS had its eye on a swath of nearly 1 million acres of tribal land up in the Owl Creek mountains. Part of the proposed restoration site encompassed the Arapaho Ranch, a chunk of several hundred thousand acres of tribal land used as a grazing site, making it one of the country’s top beef producers.

“They’ve got wolves, antelope, grizzly bears, elk ― everything but the bison,” said Keith Aune, the former head of the WCS bison program. “In North America, it was clearly one of the best prospects of bison at scale I had ever seen.”

WCS lined up support at Wind River to transfer about 100 of the first buffalo out of Yellowstone’s new quarantine program in the early 2000s. The Hot Springs County Commissioners, the Wyoming state vet, and leadership from both the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone tribes seemed to support the idea.

Still, some Northern Arapaho leaders worried about the possibility of introducing brucellosis to the ranch, despite the quarantine period. Others wanted to raise the buffalo like cattle and market the meat, putting them at odds with the proposal to keep them wild.

When the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho held a joint public meeting to consider the proposal, it failed. The buffalo, left in the lurch, went first to a Montana ranch owned by media mogul Ted Turner, then Fort Peck Indian Reservation.

“It was just kind of baffling,” Aune said. “This was a slam dunk. We thought it was already over.”

Baldes watched the events unfold from Montana State University, where he had enrolled in land resources and environment science. The future of buffalo restoration at Wind River seemed to hang in the balance of that failed vote, but Baldes worked steadily toward a master’s thesis measuring how the old Owl Creek buffalo wallows he knew from his youth impacted plant biodiversity.

The results were largely inconclusive, though three plants of cultural significance to the Eastern Shoshone — yarrow, arnica, and bluebells — were more likely to grow in depressions left more than a century ago by wallowing buffalo.

Ahead of his graduation, Baldes approached the Eastern Shoshone business council with a more modest proposal to launch a wild buffalo program on a 300-acre parcel of tribal land. The same year he defended his thesis, he moved back home to start his career as the tribe’s buffalo representative.

The Owl Creeks still offer one of the best sites for buffalo restoration in the country, as Baldes noted in his thesis. But he has little interest in resurrecting the conflict over the future of ranching there.

“Both tribes come from buffalo people,” Baldes said. “I’m not a member of the Arapaho tribe. I’m a member of the Shoshone tribe. And so I work on behalf of the Shoshone tribe to expand habitat, expand our buffalo and create more opportunities. I’m focused on what’s contiguous.”

Overcoming Inertia

Little formal opposition to buffalo restoration exists at Wind River today. The reservation’s ranchers no longer dominate the business councils, nor do they campaign against bison. Instead, the biggest problem buffalo face is inertia.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs divided most of Wind River’s tribal lands into a series of 92 range units, leased out to individuals who use them to raise cattle, like the grazing allotments found on federal public land. Baldes could apply to the BIA to run buffalo on some of those units, expanding the enclosure, but the agency would classify them as livestock, which he refuses to do.

“Cows are stupid as hell,” Baldes said. “They’ve been bred to be so dumb that they rely on man. We don’t need to do that to buffalo.”

Somewhere between 30 million and 60 million buffalo roamed North America at the dawn of the colonial period. Only 400,000 remain, with livestock accounting for well over nine in 10 of them. Early attempts at cross-breeding buffalo with cattle, which are closely related, created viable hybrids that have made genetically pure bison rare even in the handful of wild populations that survived the 19th-century killing spree.

“Buffalo belong as wildlife,” Baldes added. “If we’re talking about carbon sequestration, climate change, ecosystem integrity, biodiversity — all of those are reasons enough to restore buffalo and protect them on the landscape.”

At the national level, things appear to be changing. Deb Haaland, the first Native American to head the Department of the Interior, signed twokey orders to bolster the tribal buffalo restoration movement — order 3403 pledging support to tribal efforts to consolidate their land base for conservation purposes and order 3410, which pumped $25 million of federal money into buffalo restoration. In September, Sens. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) and Markwayne Mullin (R-Okla.) reintroduced the Indian Buffalo Management Act, which would set aside $14 million in annual funding for tribal buffalo restoration efforts, along with grants and technical support, if Congress were to pass it into law.

The swell of activity encourages Baldes, but he’d like to see more support for the work tribes are leading. Interior order 3410, he noted, heaps the lion’s share of the $25 million on parks and refuges, while setting aside only $3.5 million for the InterTribal Buffalo Council — despite the fact that tribes now hold more wild bison than all federal public lands combined.

Whether or not the federal agencies ultimately support his work, Baldes continues to sew long-severed stretches of land back together. The project currently has access to some 50,000 acres. The problem is that they don’t all share borders. While he raises the funds to buy the fee lands blocking the way, he’s also building support to convert more rangeland from cattle grazing to buffalo habitat.

As he cobbles more land together, Wind River stands a chance of building a corridor connecting winter range in the valley with spring and summer green up in the high country that buffalo historically migrated across annually — perhaps the first viable migratory route reestablished for bison since European settlement carved up the landscape with roads and fences a century and a half ago. If the buffalo corridor were to stretch far enough to the northwest or the south, it would eventually touch borders with large swaths of federal public land that would make excellent buffalo habitat, but are currently used to graze cattle.

Baldes dismisses any such speculation, which extends far beyond his self-imposed mandate to focus narrowly on acquiring the next chunk of contiguous land for the Eastern Shoshone buffalo herd.

But he does see building Wind River’s land base as a possible avenue to win back the reservation’s water rights one day.

“We can essentially challenge the state’s management of water,” Baldes said. “Prioritizing ecological integrity, keystone species restoration — it all falls in line with our history of conservation successes.”

On the last day of my visit, I hopped back in Baldes’ quad with his yellow dog Willi and Mike Vanata, a filmmaker with a YouTube channel called Western AF who had spent the last three years documenting the Eastern Shoshone’s buffalo project.

After gathering some footage of the buffalo, Baldes drove us along a fenceline, past his house and horse pasture, then toward the southern end of the enclosure, where the Little Wind River winds its way below a towering mesa.

“We’re in wallow country now,” Baldes said as we crossed the gate.

The buffalo had spent far more time there than in the pineapple-weed-laden pasture. After just a few years, they had already carved out a network of trails and wallows, some deeply dished into the dirt from repeated use.

The ground had desiccated below one of the larger ones, and the pounding sun had baked the bare mud into fissured plates, like the pattern on a turtle shell. Some still held water despite the dry August heat.

Baldes leaned over and picked up a tuft of buffalo fur from one of the wallows and began to shear it apart. Tribes like the Eastern Shoshone used it for all kinds of things — shoe insulation, pillow stuffing, textiles. The herd has seen 1,500 student visitors over the last two years. Baldes will often give young visitors a handful of fur to remember the place.

Each gift is like a seed that he hopes may germinate over time. Though he now has his own personal laboratory to study how the wallows affect biodiversity, Baldes no longer cares to carry out experiments on them himself. Instead, he hopes to use the site as a place where young folks can pursue scientific research without having to leave the community of their birth.

Besides, Baldes said — he’s always known what the wallows will do.

“We know that bringing buffalo back heals the land,” Baldes said. “And as they restore that connection, they’re going to heal us.”

Reporting for this story was made possible by an Indigenous Reporting Grant from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News