Ebola outbreak: What the fight against the virus can learn from polio

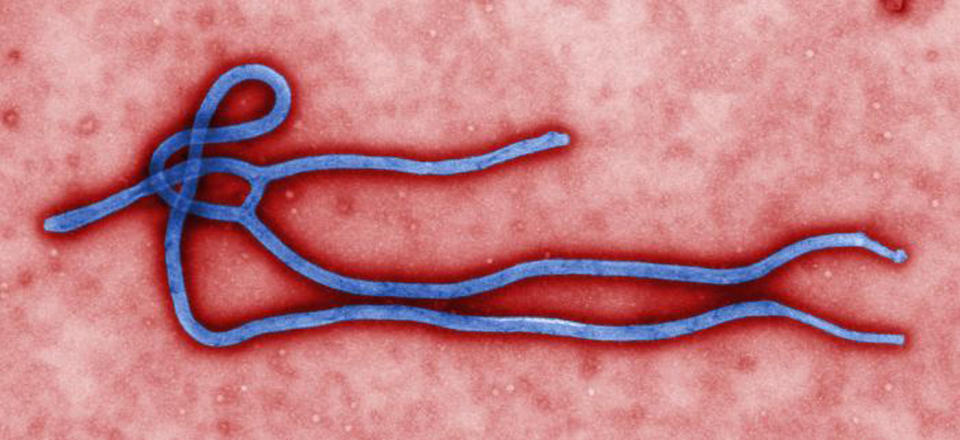

The two diseases are, of course, different: notably, the more modern scourge, which was only discovered in 1976, is far more deadly – so far killing half of those infected

Health workers battling a seemingly unstoppable contagion, a frantic race for a vaccine and public alarm over a mysterious, horrifying and ever-encroaching disease.

The scene painted could easily portray today’s panic over Ebola – yet this terrifying scenario was in fact the result of a virus that shook the western world six decades ago.

Polio, which killed thousands and left millions crippled, had – like Ebola – long festered relatively unnoticed before reaching pandemic proportions in the 1950s.

The two diseases are, of course, different: notably, the more modern scourge, which was only discovered in 1976, is far more deadly – so far killing half of those infected.

But polio – and, in particular, the mixed fortunes of different bids to eradicate it – could provide key lessons in the global fight against Ebola.

Crucially, many of the techniques used to prevent the spread of the older virus appear to have already proved effective in controlling the newer one in Nigeria.

Indeed, the country – one of four in the region to face an Ebola outbreak - is the only place in the world that has also had to battle polio in recent months.

And, as a result, it has been able to divert polio-fighting resources in the battle against Ebola, it was able to eradicate it within six weeks.

The disease continues to rage in neighbouring Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea – where an estimated 6,000 people have been infected during the last six months.

'Nigeria had a head start over other west African countries,' Professor Oyewale Tomori, a World Health Organisation virologist, writes in The Guardian.

There, officials created an emergency command centre using existing facilities that were built in 2012 by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

While there was only a trickle of cases at first, 40 of the 100 epidemiologists exerts fighting polio were also reassigned to Ebola.

They helped train 1,800 health workers, who made 18,000 visits to check the temperatures of 900 people who may have had contact with victims.

'As with polio eradication, this wasn’t easy but it was imperative to stopping the disease in its tracks,' Professor Oyewale adds.

Yet Nigeria, which has reduced the number of polio cases to six this year and is on the verge of eradicating the disease, also shows how not to tackle contagion.

A decade ago, the northern state of Kano boycotted the polio vaccine for 11 months amid rumours that it sterilised recipients and that health workers were evil villains.

It was a massive setback and allowed the spinal chord disease, which is spread by infected faeces and nasal secretions, to reach pandemic proportions once again.

'Within months, polio spread to 22 other countries, including places like Indonesia, where it was thought to have been eradicated,' says Dr Heidi Larson of the London School of Hygiene& Tropical Medicine .

'Yet the same mistrust and fear we saw over the polio vaccine in northern Nigeria, have also been witnessed over Ebola control in other parts of West Africa.

'One of the most important things that the global polio eradication initiative has learned is the importance of engaging local communities, trusted community members, and local traditional and religious leaders.'

Dr Larson said Ebola should be easier to control than polio since its symptoms – such as bleeding from the eyes and other orifices – emerge very quickly.

'The same sort of screening methods used to monitor and track polio should be able to be used even more effectively against Ebola,' she adds.

Yet polio, which left Great British Bake Off judge Mary Berry with permanently twisted spine, a weaker left hand and thinner left arm after she became one of 8,000 Britons to catch it in 1948, has one very important difference: there is a vaccine.

And this is where the lesson for Ebola may, ultimately, be the greatest if we want to eradicate it.

Ebola has already come perilously close to Britain after it emerged today that a Spanish nurse was the first person to contract it outside of Africa.

Mirroring this, the fight against polio only became a scientific priority when, in the aftermath of World War II, it became endemic in rich countries.

A vaccine discovered by American virologist Dr Jonas Salk was rolled out in 1955 – after researchers receiving vast sums of cash from the U.S. government and panicking members of the public.

Wealthy parents, realising there was little they could do to protect their children, began raising money in a bid to look for a prevention or cure.

Working class families also contributed – with 100million Americans donating at least 10 cents to the March of Dimes fund.

A similar effort against Ebola may accelerate the search for a vaccine.

Luckily, thanks to the war against polio, the battle against the modern virus is already benefiting from the research facilities that were developed following that fight.

Also, the hunt for an Ebola vaccine has been aided by vast sums of money poured into research following 9/11 amid fears of the disease being used in bio-terrorist attack.

Now that Ebola is actually in America – albeit by friendlier means (an infected traveller from Liberia) – the programme is being accelerated.

Last month, scientists began testing a dead vaccine using a killed form of Ebola – another lesson learned from polio, where initial live virus neutralisers proved fatal.

But, before we garner too much hope, Professor Tomori delivers a final warning: 'As with polio, until there are no cases of Ebola, no one is safe from the virus.'

Yahoo News

Yahoo News