Election 2024: the view from the UK’s most marginal constituency

Speaking about Northern Ireland in 1922, Winston Churchill expressed bewilderment that the radical transformation that had taken place across Europe as a result of the first world war had done nothing to change the basic terms of dispute in the region:

Great Empires have been overturned. The whole map of Europe has been changed … The modes of thought of men, the whole outlook on affairs … all have encountered violent and tremendous changes in the deluge of the world, but as the deluge subsides and the waters fall short we see the dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone emerging once again. The integrity of their quarrel is one of the few institutions that has been unaltered in the cataclysm which has swept the world.

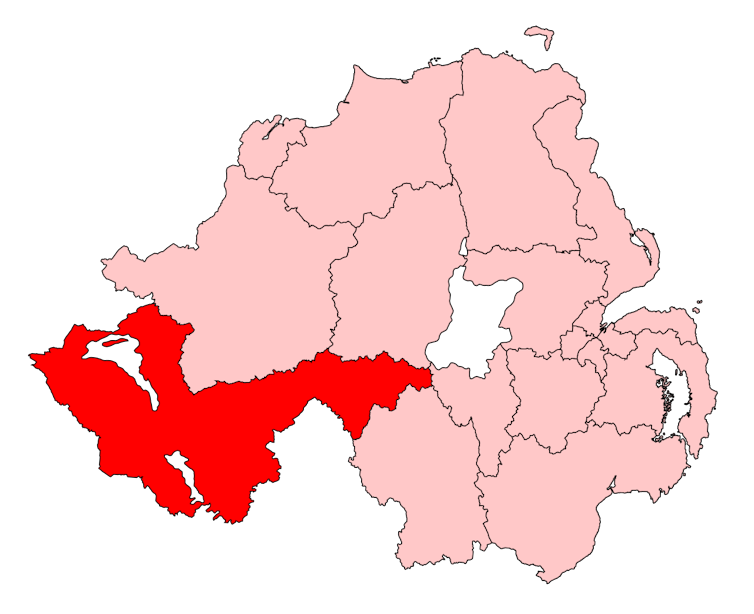

More than 100 years on, and following the convulsions of Brexit, a global pandemic, and the return of war in Europe, Churchill might have said much the same on Northern Ireland. And what he termed the “dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone” remain a focal point in the 2024 election. That’s because Fermanagh and South Tyrone is the most marginal constituency in the UK. It was won by Sinn Féin in 2019 with a majority of just 57 votes and will again be closely fought between the incumbent party and the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP). The race epitomises the political struggle at play in Northern Ireland.

Sinn Féin will seek to hold the seat, but with a new candidate, Pat Cullen. As former leader of the Royal College of Nursing, she will be recognised further afield for leading nurses right across the UK in recent strike action. Choosing Cullen as the party’s candidate for such a contested seat does two things for Sinn Féin. First, it emphasises the party’s leftwing credentials. Critics questioned these after its willingness to serve in Northern Ireland governments where it has pursued an essentially neo-liberal agenda. Cullen’s reputation as a union leader reaffirms the party’s commitment to fighting austerity. Better still, it does so by referencing a profession which most of the public claim to revere – particularly after the pandemic – even if they do so while voting for politicians who have continually squeezed nurses’ pay, forcing many to use food banks.

Choosing Cullen as the party’s candidate for Fermanagh and South Tyrone also fits with Sinn Féin’s continued efforts to modernise and indeed normalise a party whose origins lie in revolutionary violence. Sinn Féin has long travelled this pathway, and with remarkable success, becoming the largest party in Northern Ireland at the last assembly election. However, critics still raise the issue of Sinn Féin’s past, including in the Republic of Ireland, where it is also seeking power, with an election due before March 2025.

Victory for Cullen would provide another riposte to those who claim Sinn Féin is still run by the “men of violence”. How could this be when the party is now led by women – Michelle O’Neill in Northern Ireland, Mary Lou McDonald in the Republic, and figures such as Cullen. Like most Sinn Féin politicians, Cullen is keen to move the conversation forward onto matters of policy rather than the past.

Unsurprisingly, many unionists are not. Cullen’s primary challenger for Fermanagh and South Tyrone seat, Diana Armstrong of the UUP, challenged her to condemn atrocities that occurred in the constituency, including the IRA’s Enniskillen bombing of 1987. Cullen’s refusal is also consistent with Sinn Féin’s approach. Criticising the IRA would delegitimise the struggle from which Sinn Féin emerged and alienate a core component of its political base. This shows the continued challenge for the party as it seeks to extend its dominance in Northern Ireland and even become a party of government in the Republic. Opponents will always seek to remind younger or more moderate voters of its past – something which Sinn Féin can never disown without losing traditional supporters.

Always a hot seat

And the past in the Fermanagh and South Tyrone constituency (previously called simply Fermanagh and Tyrone) is a particularly controversial one, even beyond Enniskillen. Indeed, in 1981 the seat was won by an IRA prisoner, Bobby Sands. At the time, Sands was participating in a hunger strike in an attempt to force the British government to grant recognition to incarcerated republicans as political prisoners. Sands would die from his fast within a month of his election to Westminster, and nine more republican hunger strikers would perish before the tactic was eventually abandoned.

Margaret Thatcher’s staunch refusal to concede to their demands for political recognition seemed to signal a pivotal defeat for republicans. However, Sands’s election showed that they could win support at the ballot box, and republicans soon began to routinely contest elections in Northern Ireland. In effect, this shift gave birth to Sinn Féin, and shows why none if its representatives can condemn the IRA’s actions. This would be seen by core supporters as disowning the sacrifice of Sands and the other hunger strikers.

History is also apparent in Armstrong’s role as challenger to Cullen for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. She is the daughter of Harry West, the former UUP leader who stood against Sands in the same constituency in 1981. Just as Sinn Féin choosing Cullen to stand is part of its strategy to move on from the past, the UUP’s nomination of Armstrong might be seen as conscious effort to remind voters of this.

Want more election coverage from The Conversation’s academic experts? Over the coming weeks, we’ll bring you informed analysis of developments in the campaign and we’ll fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our new, weekly election newsletter, delivered every Friday throughout the campaign and beyond.

West lost to Sands by a few hundred votes, and still today the number of nationalist and unionist electors in Fermanagh and South Tyrone remains finely balanced. Indeed, winning by 57 votes last time round was a comparatively luxury for Sinn Féin. In 2010 it secured the seat by just four votes, this following three recounts. Even then the matter was not settled, as unionists made a failed effort to overturn the result in the courts. The forthcoming contest already looks likely to evoke similar passions.

Churchill was amazed by the persistence of conflict in Northern Ireland in the 1920s. A century later, and the same basic dispute endures. Thankfully, it is not accompanied by the violence which once prevailed, but the bitterness created by that past clearly continues.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Peter John McLoughlin has received funding in the past from the AHRC, Leverhulme Trust, the Irish Research Council, and the Fulbright Commission. He is a member of Greenpeace.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News