Errol Morris’s Henry Kissinger Project? Not Gonna Happen. Director Says Foreign Policy Giant “Got Cold Feet” – Telluride

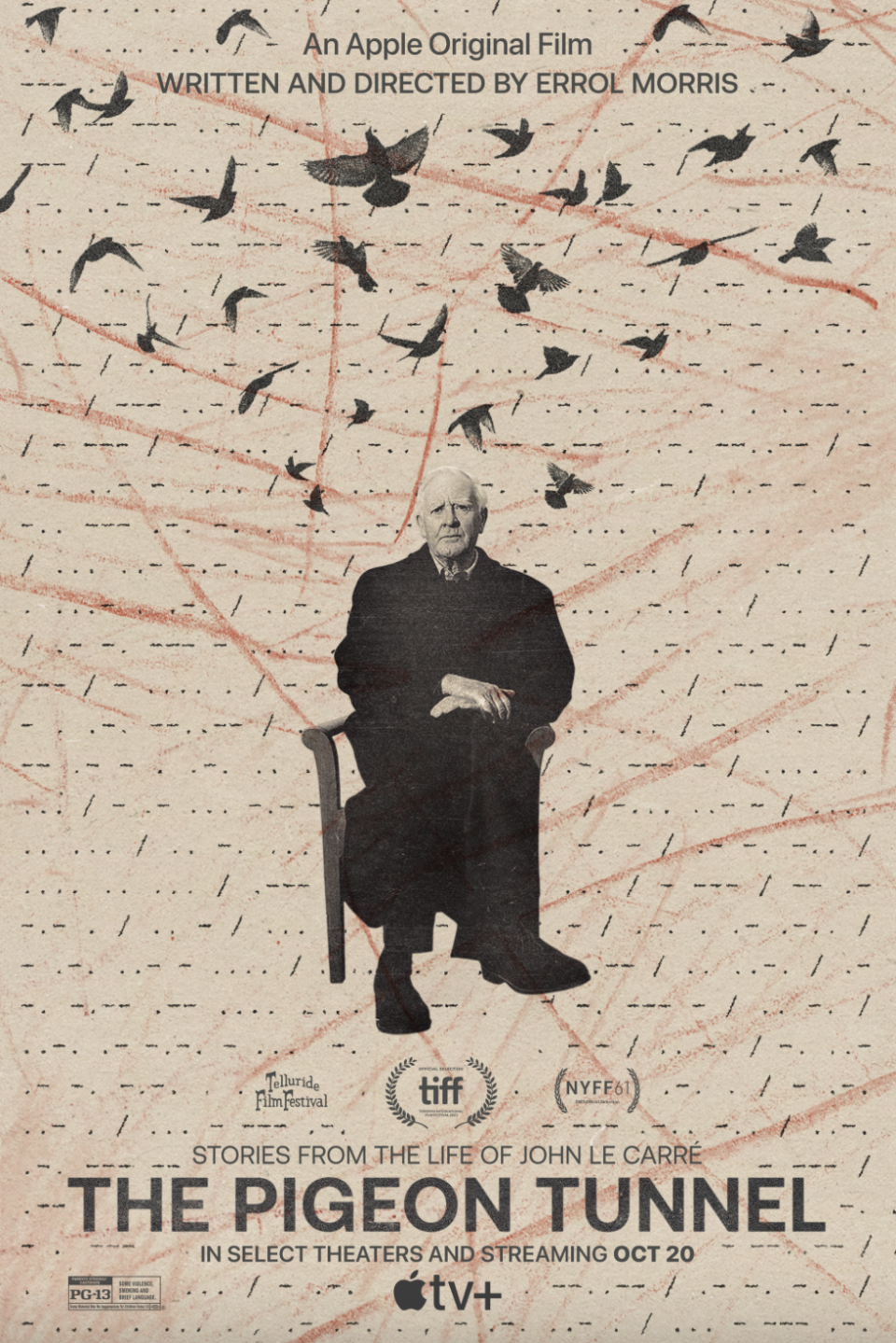

Oscar-winning filmmaker Errol Morris unveiled his new documentary The Pigeon Tunnel – about the spy-turned-novelist David Cornwell, aka John le Carré – at the Telluride Film Festival on Friday. Audience buzz afterwards ranked it among Morris’s best work, a canon that includes the classics The Thin Blue Line and Gates of Heaven.

Morris said it took years for The Pigeon Tunnel to be completed. But during a Q&A, he referenced a different endeavor that apparently isn’t fated to come together – a nascent documentary project on former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. The controversial figure who guided American foreign policy during the Nixon and Ford administrations recently reached the century mark.

More from Deadline

“Someone wanted me to interview quite recently, on the occasion of his hundredth birthday, Henry Kissinger,” Morris told the audience at the Chuck Jones Theater in Mountain Village. “And as my wife has pointed out, we talked on the phone for over an hour. He got cold feet.”

Morris added, “I thought I was being perfectly nice. Did not want to be interviewed by me.”

That revelation will come as a great disappointment to Morris fans, who know what the filmmaker can achieve with a subject as ripe for exploration as Kissinger. Morris’s Oscar-winning documentary The Fog of War chronicled the regrets of former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, architect of the Vietnam War during the Johnson administration. Morris also memorably went toe-to-toe with former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who presided over the George W. Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq, in The Unknown Known.

Morris brought up Kissinger in the context of influential figures who espouse a cyclical view of history, meaning they believe certain external forces guide human events toward ineluctable ends. This, the director said with evident disdain, neatly absolves someone like Kissinger of any responsibility for his actions.

The point was to contrast a Kissinger – or Stephen K. Bannon, the Trump advisor and subject of the Morris documentary American Dharma – with David Cornwell. Before he became a bestselling author of espionage novels, Cornwell served in Britain’s domestic intelligence service, MI5, and then the foreign intelligence service, MI6.

“He goes to Germany in the early ‘60s, he’s a spy, a diplomat. And correct me if I’m wrong,” Morris added with his characteristic arch humor, “we fought this war, what was it called? World War II, to defeat Nazi Germany. He gets to Germany and the Bundesrepublik and all of a sudden, he realizes it’s filled with Nazis.”

(That triggered an amusing exchange with moderator Michael Barker, co-head of Sony Pictures Classics, who noted the post-war Germans in question were “ex-Nazis,” as indeed Cornwell described them. Morris responded wryly, “Maybe. Once a Nazi, always a Nazi. You’re talking to a Jew! Ex-Nazi, my ass.”).

Cornwell, in the film, says in the post-war period there were Nazis (“ex” or otherwise) freely walking around both West Germany and East Germany. This left him with a sense of moral disillusionment about the burgeoning Cold War conflict: “East and West,” he says, “were inventing the enemy they needed.”

The Pigeon Tunnel, based on Cornwell’s 2016 memoir, debuts on Apple TV+ on October 20. In some of the film’s most striking scenes, Cornwell expresses almost visceral loathing for Kim Philby, the very senior British intelligence officer who was unmasked as a Soviet agent in 1963 – during the time Cornwell was posted in Germany. Philby was part of the Cambridge Five who became spies after exposure to Marxist ideology in their youth and went on to serve the interests of the Soviet Union throughout Stalin’s reign and beyond. But in the film Cornwell says ideology became entirely secondary for Philby at some point; foremost was the allure of deception and double-dealing, and of feeling he occupied a place at the fulcrum of world history.

Cornwell damns Philby for continuing to serve his Soviet masters long after Stalin had been revealed as a madman and mass murderer.

“I felt this very strongly in David’s work. It’s really distressing,” Morris said, again deploying that ironic sense of humor, “he’s far less cynical than I am in his cosmology. There clearly is right and wrong, good and bad, good and evil… Communism, Stalin – bad.”

In the Q&A Morris attempted to discern the source of Cornwell’s perspective. “Is it love of England, love of the United Kingdom? Not exactly, but it is a kind of, dare I say it, patriotism. A real belief in queen and country and I envy that,” Morris said, joking, “What do I believe in today? I believe in crawling under the bed and sucking my thumb and hoping it all comes to an end quickly.”

(I think it’s not so much love of queen and country that guided Cornwell, but rather a basic sense of loyalty – that he had committed to acting in the interests of certain ideals, a decision that presented him with clear moral obligations).

Simon Cornwell and Stephen Cornwell, two of David’s sons, are producers on the film and participated in the Q&A panel. The elder Cornwell did not get to see the film before his death in 2020 at the age of 89. But the sons said they thought he would have liked it.

“Our dad was fascinated for a long time by Errol before they ever met,” Simon Cornwell said. “He always talked of The Fog of War as one of the films that shaped his perception of truth and history and reflection.”

Dominic Crossley-Holland, a fellow producer on the film, said that even though Cornwell admired Morris’s work, “David came into this incredibly wary. When I first met him, he interrogated me about Errol’s motives. He watched every pixel that Errol had generated and he spied on me at the beginning of the process. When we began making it, he sent us out to meet some old colleagues of Ronnie [David’s father]. And I found that when I next met him, he’d rung up the old colleagues. He said [to me], ‘I hear you’re asking this about me. Why? Is Errol interested in this?’”

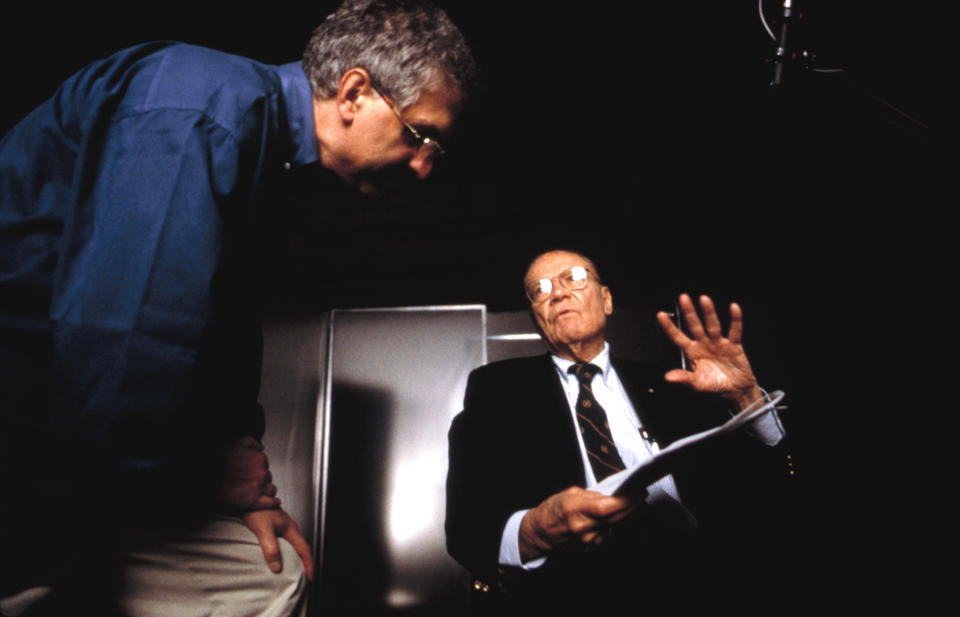

Crossley-Holland recalled the preparations for the interview sessions between Cornwell and Morris that would form the crux of the film. The conversations were filmed at a grand estate outside London.

“We were there for four days, and Errol was in the east wing and David in the west,” Crossley-Holland recounted. “And just before the beginning of the interviews began, Errol and David converged in the lobby between the east and west wings to size each other up for one moment, like a Cold War exchange, a no man’s land.” He added, “David [had] worked out a strategy as an interrogator himself, [inquiring at the outset] ‘Errol, who are you?’ He began trying to put Errol on the back foot… Errol and David, I think, had met their match.”

Best of Deadline

Venice Film Festival 2023 Photos: David Fincher, ‘The Killer' & 'The Beast' Premieres

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News