ESPN's Malika Andrews' Reveals Secret Teen Trauma, Including Wilderness Therapy: 'So Focused on Surviving' (Exclusive)

'NBA Countdown' host Andrews was sent to a residential treatment for three years when she was a teen. Today she still struggles with mental illness

Bethany Mollenkof

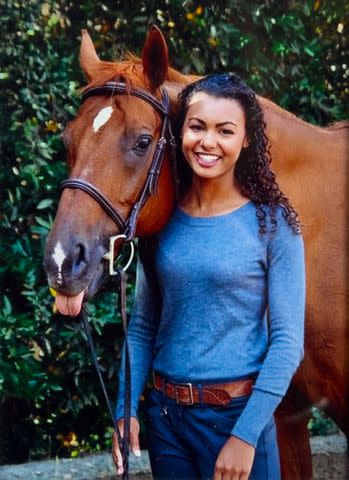

Malika Andrews with her horse Val, photographed in May 2024 in L.A. for PEOPLE.Malika Andrews, 29, is the host of ESPN's NBA Today and NBA Countdown and the first woman to host the NBA Draft

As a teen, Andrews spent three years away from home in residential therapy institutions to treat depression, anxiety and an eating disorder, including at a controversial wilderness therapy program

Andrews talks about her struggles for the first time in this week's issue of PEOPLE and says she continues to live with the symptoms of mental illness

For the past seven weeks, since the NBA playoffs began, downtime has been a rarity for Malika Andrews. “I’m in a stretch of 32 days straight on camera. I think my eye is twitching,” Andrews jokes as she joins a Zoom interview from her L.A. home between duties hosting ESPN’s pregame show NBA Countdown and NBA Today.

Jeff Haynes/NBAE via Getty

Malika Andrews hosting the 2023 NBA Draft with ESPN colleague Adrian Wojnarowski.But when she does have an hour to spare, Andrews escapes to a riding stable a short drive from the ESPN studios “where I can exhale when things feel overwhelming,” she tells PEOPLE in this week's issue. There she saddles up Val, a 19-year-old chestnut warmblood with a white blaze and an attitude. “He’s tricky. He's a big mover and he's got lot of opinions” says Andrews, 29. “You need to be strong to ride him.”

Since joining ESPN in 2018 at the age of 22, Andrews has proven her mettle. In 2020, she quarantined for 107 days as the network’s reporter inside the NBA’s COVID bubble. Two years later, she became the first woman to host the NBA Draft, a role she will repeat at the end of this month. Known for her unflappable delivery and polished style and substance, Andrews admits, “I feel so much pressure as a woman in a male-dominated industry to show up as my most perfect self.”

At the same time, she’s held a painful, imperfect, truth. As a teen she struggled with mental illness that took her away from her family for more than three years — and she continues to cope with symptoms. For the first time, she’s sharing her story “in hopes that we see people with more compassion,” she says. “You don’t know what somebody’s going through. There’s an expectation that struggling — depression, anxiety, eating disorders — looks a certain way. I was told it doesn’t look like me. But it is me.”

Bethany Mollenkof

Malika Andrews with horse Val photographed for PEOPLE in May 2024."This is not a before-and-after story. We are all unspooling works in progress."

Malika Andrews

For much of her life, Andrews avoided questions about her teen years: “I was embarrassed. I would get the sweats when people would ask me, 'Where'd you go to high school?' It's such an innocuous question but I didn't want to go down that path."

It was easier to talk about growing up in Oakland, Calif., with sister, Kendra, also an ESPN reporter, and parents Mike, a personal trainer, and Caren, an artist. “We were — and are — a tight-knit family," she says. Her parents still live in the house where she grew up and where the family had dinner together each night. Andrews loved to play “every sport I could,” and watch the Golden State Warriors with her basketball-loving family.

As a biracial kid, Andrews "stuck out like a sore thumb" in her predominantly white, private school, where she was well-liked and a strong student. However, by the age of 12 she started lashing out and showed signs of disordered eating. "I remember going to a lunch one time with a bunch of girlfriends and chewing up a hamburger and spitting it into a napkin," she says. "One of my girlfriend's moms was there and asked me if I didn't like my food. I was so mortified that someone saw me. That was sort of the beginning of what's been now a decades-long battle with food and body image for me."

She wrote in her journal at the time: “Everyone keeps asking what happened. Why am I not happy anymore? I wish I had an answer... No one else seems as mad and sad as me all the time.”

By eighth grade, she was in therapy for depression, but she was failing classes and didn't seem to care. She wasn’t invited back to her rigorous K-12 school. Then, in March 2009, after a violent argument with a friend, Andrews admitted to her mom she’d considered self-harm. “I was crying and said, ‘I know I need help.’”

A therapist told her parents to take Malika to the ER, where she was placed in a psychiatric hold. “We were confused and scared,” says Caren, 63. “I don’t think any of us understood the journey our family was embarking on. It was hellacious.”

It would be more than three years before Malika moved back home. “It was like having our familial heart ripped from our body,” says Caren. "It felt wrong living a life without our core four; it was a life of disequilibrium."

Instead of improving in the psych unit, Andrews learned new, dangerous behaviors like cutting. “I was clawing at ways to make sense of my anger,” she recalls. “I didn’t know how to live in my own skin.”

When insurance ran out, she was moved to an eating disorder program. But “they told me they weren’t equipped to deal with all the stuff I had going on.”

Malika’s parents were “on the brink of a breakdown,” says Caren. “Malika was not safe at home. What were we to do?” An educational consultant suggested Wingate Wilderness, a therapy program in Utah that has since gone out of business. “Wilderness was a hard sell," says Caren. "But Mike is a 'mountain man.' Whether on a dirt bike, mountain bike or skis he finds inner peace in the backcountry. We were afraid, but wanted our daughter back. Wingate was a leap of faith.”

Courtesy Malika Andrews

Malika Andrews in 2001 with horse Dante.Because Malika's parents knew how emotional taking her away would be for everyone, the consultant recommended they hire “transporters” to bring her to Wingate. "My parents told me on a phone therapy session that I would be leaving, so I knew they were coming — I had packed up," Malika says. "My parents felt so lost. I know it was hard on them. That was the way that they felt that they could love me the best."

At the end of April, a man and woman arrived in the middle of the night: “Don’t try to run,” they told Malika. "I wasn't thinking of running," she says. "I had felt so much shame where I was."

The pair accompanied her on a flight to Las Vegas and then a four-hour drive into the Kanab desert. She spent eleven weeks in the desert with other troubled teens, hiking up to 12 miles per day with a 50-lb. pack, building fire and shelter. "They give you one roll of toilet paper and like 10 tampons," she says. "They give you dried beans, powdered milk, powdered cheese, dried pasta, rice, packets of tuna, dried tomatoes, a little thing of brown sugar, a little thing of dried oats, an apple, an orange. That's your food for the week. They give you a tarp and some rope and you have to create a shelter."

If she wasn't able to build a fire, she didn't eat hot food. When she went to the bathroom, she had to count to prove she wasn't making a run for it. At night, her shoes were taken away.

“You’re so focused on surviving, it doesn’t leave room for the overwhelming hurt I’d been feeling, so it can give some semblance of working,” she says. But throughout the ordeal, she’d find sharp rocks and continue to cut. And when it was over, her problems hadn’t gone away.

Instead of returning home, she was moved to an all-girls residential treatment center in Utah, where she lived for nearly two years under strict supervision. "If you did positive things, you earn positive points. If you do bad things, you earn negative points. If you leave your sock out in morning room checks, you get 2,000 negative points. There was a family teacher who infamously would get down on her hands and knees to check after you mop or sweep and if she found more than six spots of dust, then you earned 2,000 negatives for not doing your chore well enough."

She could lose privileges, like calling home, if her negative points were too high. And when she could call her parents, her calls were monitored — and she was forbidden from saying she wanted to go home.

"In that very controlling environment, purging started to really pop up again for me. Cutting was something that would come up," Andrews says. "And I ran away once, but I didn't get very far. The teachers ran right after me."

Courtesy Malika Andrews

Malika Andrews (right) with parents Mike and Caren Andrews, and sister Kendra Andrews in 2021.One rare source of happiness in those years was the time she was able to spend with horses. At the final residential treatment school in Utah where she lived for more than a year, she was granted off-campus privileges to take riding lessons and she met a horse named Dante. He was a "firecracker of a horse, all go," and bore a striking resemblance to the horse she now leases to ride, Val. "I started working with him and I fell in love. Suddenly I had something to pour joy into,” says Andrews, who later brought Dante home to California, where she rode him until college, when she gave him to two close friends.

Andrews says she was never abused in treatment, but the tactics left a mark. For years, she wouldn’t wear the color orange because in one institution “when you got in trouble, you’d wear an orange shirt so people knew not to talk to you.” Says Andrews: “I was a lost kid, but I wasn’t a bad kid. Little me didn’t deserve that. I did deserve help.”

And yet, she has come to peace with her past: “Everyone deserves help tackling their demons and sorting through this messy life. Not getting the perfect assistance immediately hurt me. I struggled longer because of it. There are moments I resent the institutions that didn’t have my perfect life raft ready, but forgiveness is an essential part of becoming whole. It can take time to find the right kind of help because there isn’t a mold — a one-size- fits-all.”

Courtesy Malika Andrews

Malika Andrews with fiance ESPN reporter Dave McMenamin in 2021.Of her parents’ decisions, she says, “I have the best parents in the world. They did all they could to help me. There’s no bigger support system.”

After she finally returned home in August 2012, she had missed many of the normal rites of passage for teens. "Do you know how much life happens in four years between 14 and 18? I felt like the world had moved on without me," she says. Her little sister Kendra, who had been her best friend before she went away, had grown as well. "I had left her as a kid and now she was going to prom."

Kendra, who also works at ESPN as a reporter, says her sister is “one of the strongest people I know, Every step on her journey, her success, didn’t happen by accident. There was so much hard work. And it takes courage to open up about the hard things in your life.”

Andrews found her passion studying journalism at the University of Portland and becoming editor of the school paper. "Writing and sharing other people's stories is something I found a lot of purpose in when I went to college," she says. However, before she graduated in 2017, she relapsed with her eating disorder, losing 40 pounds after purging multiple times a day and ending up with an irregular EKG.

For more on Malika Andrews, pick up this week's issue of PEOPLE, available Friday.

"When I was struggling so badly in college, I was told I was medically unstable and that I needed to get treatment, but I didn't want to," she says. "I didn't want to miss more of my life. I felt like there were already so many normal things I never got to do. And I didn't want my family who I'd put through so much to worry about me." Even now, she says "my relationship with food is not perfect,” she says. “It’s something I have to actively care for.”

One of the ways she finds balance today is returning to the place that brought her joy as a teen. A few years ago Andrews’s fiancé, Dave McMenamin, 41, an ESPN reporter, gifted her with riding lessons. "I believed I didn't have time or space in my life for it anymore," she says. “But he helped me prioritize riding again. Horses have been my bright spot.”

“When people see somebody like me on TV, the thought is that you have it all together. But everybody has something, and you have to learn to care for your something. That’s what I’m trying to do.”

Malika Andrews

Mental illness, she says, is a “shape-shifting monster” that’s never really defeated. “We talk about depression and recovery as a ‘before and after,’ something you overcome. My experience is it’s something you contend with every single day,” she says. "Depression, anxiety, eating disorders, anger — they are shapeshifters that can grip and control you and just when you feel like you have a handle on one piece, another juts out to slice into your progress."

But, Andrews says, continuing therapy along with support from her family and McMenamin makes that a little easier. “I have a job I love, a partner I love, a life I love that’s worth fighting for,” she says. "That doesn’t mean that it isn't difficult a lot of days. I’m still finding my way.”

Bethany Mollenkof

Malika Andrews photographed for PEOPLE in May 2024.If you or someone you know needs mental health help, text “STRENGTH” to the Crisis Text Line at 741741 or visit crisistextline.org.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News