‘Eventually it will just be a barcode, won’t it?’ Why Britain’s new stamps are causing outrage and upset

Dinah Johnson sounds a little anxious when I suggest that she try to subvert the will of Royal Mail. As the founder of the Handwritten Letter Appreciation Society, Johnson is a huge fan of the postal service. Since the society’s launch in 2017, its members – now more than 700 of them – have romanticised the rituals of stamp sticking and envelope sealing. But all is not well in this postal paradise and Johnson fears that the British stamp, a symbol as potent as any national flag, is under threat.

In February, Royal Mail introduced a new design for its standard stamps, which have changed so little since the launch of the Penny Black in 1840 that they are officially known as “definitives”. The new stamps – “plum purple” for first class, “holly green” for second – still feature the same regal profile introduced more than 50 years ago. But what is most bothering purists – and leading Johnson to the brink of direct action – is the addition next to the Queen of a digital barcode.

The rectangular codes – which look like QR codes but are apparently not QR codes, which are a particular, and trademarked, kind of code – are designed to stop counterfeiting and to enable the tracking of all letters to improve efficiency. Correspondents will soon be able to share photo or video messages by linking digital content to their coded stamps. Recipients will view it via the Royal Mail app (currently the codes link to a short film featuring Shaun the Sheep and a plasticine postwoman).

From 1 February 2023, only the new stamps will be accepted. Any old stamps must be used before then or traded in. Christmas and other themed special stamps will remain valid indefinitely. Swapping definitives, which can still be done after the deadline, is free but will involve downloading and printing a form, or requesting one by phone or letter, and posting it to Royal Mail along with the old stamps.

Royal Mail describes the change as a postal “reinvention” that connects stamps to the digital world for a new generation. “But the whole point of my society was to give us a break from having to be engaged with digital content,” says Johnson, 49, from her home in Swanage in Dorset. She is also reminded of the way the Prince of Wales once described a National Gallery extension as “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend” – except this time the “elegant friend” is the Queen.

When letters started arriving bearing the carbuncle codes, Johnson asked a printer friend to make her some stickers to cover them so that only the section of stamp featuring the Queen’s head could be seen. She now adds the stickers, which bear an image of a red postbox, to the code before she files letters away in their envelopes. “This is my mini private protest,” she says.

But, until I suggest it, Johnson has not yet dared deface an outgoing coded stamp. “It would be quite an act of defiance, wouldn’t it?” she says. I promise to visit her in prison. “He made me do it!” she says, practising her defence. Eventually she agrees. In perhaps the lowest-stakes act of sedition ever committed, Johnson writes me a letter, covers the code with one of her protest stickers and pops it into her local postbox. “I hope it finds you!” she says in a text.

I can’t remember the last time I needed a stamp. I’m still working through the leftovers from the wedding invitations I sent out seven years ago. I don’t do Christmas cards, kidding myself that my preference for digital communication is about saving trees rather than rank indolence. Yet I’m aware that stamps inspire strong feelings.

Since the launch of the Penny Black as the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, the sticky squares have become more than a simple proof of purchase: they are collectibles, artists’ canvases, tools of propaganda and cultural icons.

Before 1840, postage was typically charged to the recipient, who could refuse to pay. Costs were high and complicated, and fraud was rife. For example, MPs and peers could post items for nothing. It was a widely abused privilege – in the 1830s, politicians were writing an improbable 7m letters a year.

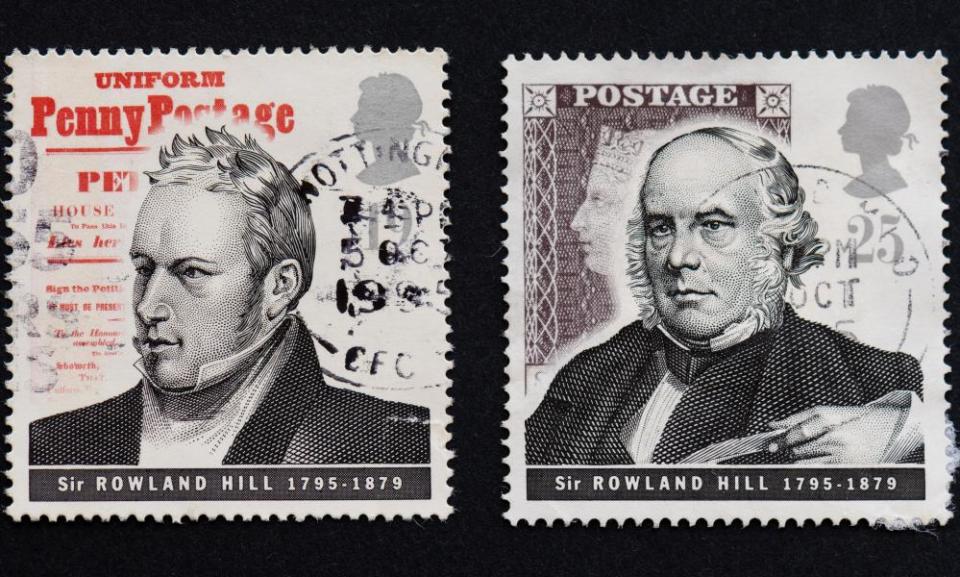

Rowland Hill, a schoolmaster turned social reformer, had no official standing. But he took it upon himself to propose radical change. In a research paper he posted to the government, he proposed a pre-paid stamp with the flat cost of a penny.

In the first year of the Penny Black, the number of letters sent more than doubled – then doubled again by 1850. Letter writing stopped being an elite pursuit and the postal service became profitable. Dozens of countries swiftly copied Hill’s example. Stamps were as significant an innovation in communication as telephones or web-connected home computers would be.

The first stamp was also a triumph of design. There was no need to include a country name – there were no stamps anywhere else, after all. Instead, a portrait of Queen Victoria in profile was added. Monarchs and colours have come and gone, and perforations and self-adhesion arrived. But the definitives have changed little in 180 years. The current stamps, originally designed by the artist Arnold Machin, have used the same sculpted profile of Queen Elizabeth II for the past 55 years.

Yet I am not alone in barely using them; the pandemic has only hastened a postal freefall, from a peak of just over 20bn letters sent via Royal Mail in 2005 (in the same year, the proportion of UK households with the internet tipped over 50%), to fewer than 8bn in 2020-21. These figures include commercial post; the smaller number of cards and letters bearing sticky stamps is likely to be in steeper decline.

“They’re trying to attract the younger generation by throwing in a QR code and a video of Shaun the Sheep,” says Andrew Jackson, 58, a collector and trader who runs Tagula Blue Stamps. Like Jackson, Johnson wonders if the change signals the beginning of the end for stamps. “Eventually it will just be the barcode, won’t it?” she says.

David Gold, the head of public affairs and policy at Royal Mail Group, knew the coded stamps would create a stir. “Collectors, traditionalists and royalists feel a sense of ownership over stamps,” he says. It’s why the new stamps, the designs for which had to be approved by Buckingham Palace, include a fake perforation as a kind of dignity screen between code and Queen (who is also, notably, facing the other way).

Gold says the codes mean Royal Mail can track all letters, allowing it to better monitor, predict and respond to regional changes in demand, for example. He is also confident the unique codes will stop the fraudulent washing of postmark ink and resale of used stamps – a crime that he claims costs Royal Mail “tens of millions” of pounds a year.

Royal Mail says the codes contain only the identity of that stamp, and cannot include personal data. Gold also rejects the notion that the stamp is endangered. “Clearly the direction of travel is a reduction in the number of letters, but I think people are still fascinated and motivated by stamps,” he says.

Gold points to the popularity of commemorative or special stamps. Such stamps were rare before the early 1960s. The government invited artists to submit designs for stamps to mark National Productivity Year in 1962, a scheme endorsed by employers’ federations and trade unions. Three designs by David Gentleman made it into circulation. In 1964, the renowned artist suggested in a letter to Tony Benn, the new postmaster general, that stamps could continue to benefit from more interesting designs.

Benn, who was a keen republican, shared this view, but in a push for more space to play with on such a tiny canvas, the men soon learned the perils of messing about with stamp design. “I suggested that the Queen’s head could be done without, which naturally never came about,” says Gentleman, who is now 92.

Ultimately it was the Queen who forbade the removal of her own head, which infuriated Benn. Gentleman came up with a compromise: a simpler portrait of an even younger, uncrowned Queen by the artist Mary Gillick would be used. The much smaller silhouette, which is still seen on special stamps, left more space for new designs.

Over almost 40 years, Gentleman, who was also renowned for his watercolours and engravings, designed more than 100 stamps. In February 2022, Royal Mail reissued six of them to commemorate its most prolific designer. They included an image of an oak tree, and a tribute to Thomas Hepburn, a 19th-century coal miner and social reformer.

Royal Mail now produces more than a dozen sets of special stamps a year in an attempt to create demand among collectors. This year they include pictures of cats, birds, the Rolling Stones and heroes of the Covid pandemic drawn by children.

Many state-owned postal services are much bolder. In Ukraine in April, queues formed outside post offices when Ukrposhta issued 1m stamps to commemorate the defiance of the soldier who refused to surrender an island soon after the Russian invasion. In the image, the solider is flipping the bird at the Moskva warship, which was later sunk, in a visual representation of the message he had radioed to the ship: “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.”

But the potential for stamps to punch above their weight is doing little to boost demand. Gentleman says he rarely uses more than a pack or two at Christmas, preferring email for everyday correspondence. He’s not sure about the aesthetic appeal of the coded stamps. “I find it difficult to enthuse over them,” he says.

Some critics have been blunter. “Arnold Machin’s profile of the Queen is one of the simplest, purest compositions in the world,” tweeted Samuel West, actor and stamp collector, in March, addressing his next sentence to Royal Mail: “You took one of the great iconic stamp designs, and you fucked it up.” The writer and broadcaster Victoria Coren Mitchell simply said: “THIS IS AWFUL!”

The implications were more practical for some. Many canny letter writers buy stamps in bulk to avoid being hit by future price rises. Royal Mail’s swap scheme is designed so that nobody loses out, but I gather many collectors find themselves in a bind. Old definitives might have a higher value because they are rare. But some of that value comes also because the stamps could theoretically be used. Swap them and you’d throw away all of that value. Keep them and you’d lose much of it anyway. “A lot of value is just going to be lost overnight,” says Gerard McCulloch, an Australian collector better known as the Punk Philatelist.

Meanwhile groups representing older people say that, as well as creating inconvenience, the change risks marginalising those who still rely on “snail mail”. These users are also affected most by price rises (first-class stamps went up by 10p to 95p in April). “It will be chicken and egg,” says Dennis Reed from the campaign group Silver Voices. “Less people will send letters so Royal Mail will say, ‘We won’t have as many collections or post boxes’ – and even fewer people will send letters.”

Royal Mail, which announced plans to lay off 700 managers in January, insists it remains committed to serving everyone, and making stamp swapping as easy as possible. “I have sympathy with all our customers who feel this is something they don’t understand or see a need for, but I genuinely believe that the improvements in efficiency and security will benefit all our users,” Gold says.

A couple of days after Johnson’s text, an envelope lands on my mat. I get that novel thrill that now greets the arrival of any handwritten correspondence. The stamp is postmarked as normal – we have succeeded. “I feel very led astray by you,” Johnson writes, adding a hand-drawn smiley face.

Gold is amused to hear about our plot, and says that, while he had not considered such a scenario, he can see no issue with code concealment before the 2023 deadline. “But going forwards the barcode will be an essential part of the stamp,” he adds.

A few days earlier, Johnson, who is well aware that there are bigger things to worry about these days, wrote a letter to Simon Thompson, the CEO of Royal Mail. She shared an image of it via the Handwritten Letter Appreciation Society’s Twitter account (she is no luddite). “Please, please write a letter [and] use a pure and simple, beautiful stamp … with no QR code,” she wrote. “Write to your wife/partner/children … and tell me if you think it can be bettered with a bit of gimmicky tech. For me it’s a definitive ‘no’.” At the time of writing, Johnson had not received a reply.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News