Exclusive: Novak Djokovic’s Father on How He Made His Son a Multiple Grand Slam Champion

Novak Djokovic just lost a tennis match. And he has an eye infection.

If you were Andy Murray or Roger Federer, the Serb’s main rivals in professional tennis, those two seemingly mundane facts might be reasons for optimism. After all, the last time either of them beat Djokovic in a Grand Slam tournament was when Murray did it over two years ago, in the 2013 Wimbledon final.

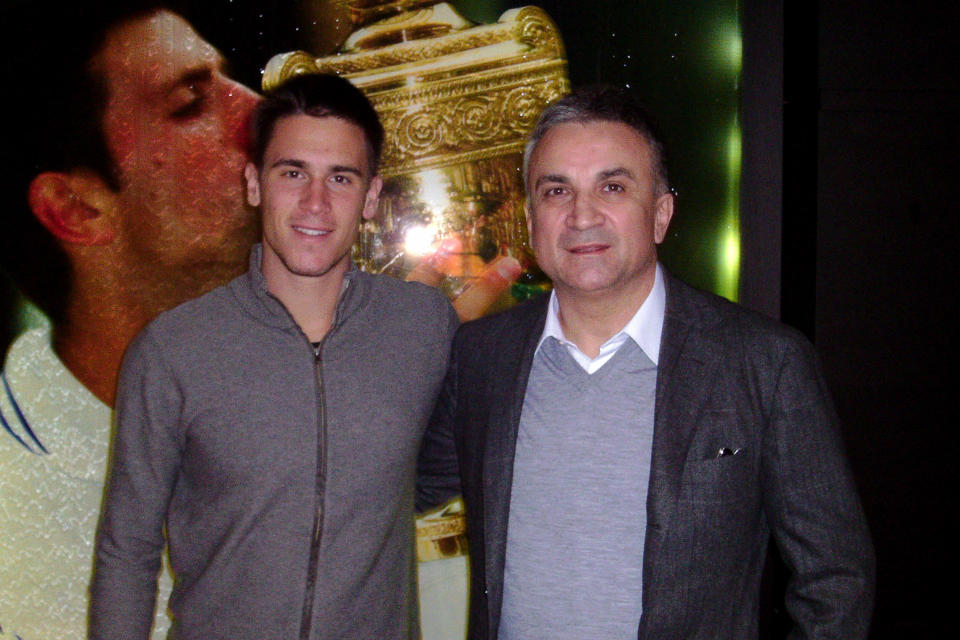

But the father of the man dominating men’s tennis sees no cause for concern. Sitting in the Belgrade, Serbia, restaurant he owns and has named after his oldest son, he shrugs off this aberrant bit of bad news for his boy and throws his doubles partner under the double-decker. “Zimonjic was not on form,” says Srdjan Djokovic, referring to Nenad Zimonjic, who was paired with Novak in a Davis Cup doubles match for Serbia against Kazakhstan.

Srdjan also knows the oldest of his three sons doesn’t lose very often. Novak won the Australian Open at the start of the year, his fourth Grand Slam out of the past five. The French Open in May is the only major he has yet to win. He has 11 Grand Slam titles, six fewer than Federer, who holds the record. In other words, Novak lost through no fault or ailment of his own, so Murray and Federer had best look elsewhere for succor.

Novak’s dominance in the most competitive era in men’s tennis is astounding, given the rivals he has bested. Spain’s Rafael Nadal is one of the all-time greats—he’s won 14 Grand Slams and is now ranked fifth in the world—but he has been slowed by injury. Switzerland’s Federer has an almost unassailable claim to be the greatest player of all time, but he hasn’t won a slam since 2012 and is ranked third. Britain’s Murray is ranked second, but the gap between him and the Serb often seems very wide; Novak has won 22 of their 31 matches.

Novak’s natural talent is key to his success, of course, but he has built his climb to the top on a foundation of support provided by his devoted and loyal family. At the center of the Djokovic family support network is Srdjan, who makes no apologies for the way he favored the oldest of his three sons. Once he realized Novak had a special talent, he says, e veryone else had to come second. “Only Novak mattered,” Srdjan says. “All of us—even his own family and his coaches—were unimportant. Everything was done to make Novak achieve what he has achieved today. As soon as I saw a small thing not going as planned, I would go somewhere else, for another coach.”

The pushy tennis parent has long been a blight on the modern game, but Srdjan insists he wasn’t driving his toddler to be a great athlete; he explains that he felt an obligation to nurture his son’s very evident and abundant talent. “Parents are unrealistic with their careers and dreams. They decide that their child is great and put so much pressure on the child that it cannot handle it. When it grows up and learns how to live, chaos comes. The whole family is destroyed. I didn’t decide that Novak was a talent, because I am not a tennis player. I listened to the advice of others.”

As a young man, Srdjan worked as a professional skier and ski instructor. He later opened a restaurant and sports equipment business in the Serbian mountains. In May 1987, Srdjan’s wife, Dijana, gave birth to Novak, their first child. Early on, they gave him a mini-racket and a soft foam ball, which became, his father says, “the most beloved toy in his life.”

“We took table tennis bats, put obstacles in the middle of the carpet and played on our knees,” says Novak’s youngest brother, Djordje, 20, whose tennis career has been put on hold because of an injury. (He is studying business as a backup plan .) “We were breaking stuff all around the house and Mum complained, but Dad said, ‘Don’t stop them, this is what they love to do.’” (The middle brother, Marko, 24, was also a professional tennis player and now works as a tennis coach for children.)

At the age of 4, Novak attended a tennis camp in Novi Sad, an hour from Belgrade. Srdjan recalls him “hitting the same backhand at 4 years old as he is hitting today.”

Jelena Gencic, Novak’s first coach, told Srdjan that the only player she had seen with as much talent at that age—Novak was then 7—was Monica Seles, who won nine Grand Slam titles on the women’s tour. Srdjan acted on Gencic’s assessment and took his son to train at academies in the United States, Italy and Germany. “In 10 years, I was never apart from him,” he says. “We were always together. Everywhere we went, everybody else had a team—physios and coaches. Everybody else was taken care of, except us.”

The travel and training was a financial drain on the family, and Srdjan took out high-interest loans to help pay for his son’s tennis education.

Slowly, Srdjan increasingly entrusted the care and training of his son to others. Just before Novak turned 13, he left Serbia for the Niki Pilic Tennis Academy, near Munich. Srdjan could not afford to join his son there. Pilic, a Croatian who was once ranked sixth in the world, was now the coach of an unusually disciplined 12-year-old. “One day, Novak was 20 minutes early for practice,” Srdjan says. “Pilic asked Novak, ‘Where are you going?’ And Novak said, ‘I need at least 20 minutes to warm up.’” For practice.

It was a discipline Srdjan had engrained in the boy. “It is most important to keep your body healthy,” he says. “And it’s why he almost never gets injured.”

Novak improved rapidly throughout his teens, and soon he was among the world’s top players. But he was unable to break the lock Nadal and Federer had on the top two places until 2011, when he won the Australian Open, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open, going undefeated until the French Open semifinals in June. The winning streak ran to 43 matches and lifted Novak to No. 1 for the first time.

When Srdjan talks about his son’s rivals, he can’t stop himself from speaking yet again of an incident during the 2006 Davis Cup involving Federer. “Novak was just 19 at the time. He had a deviation of his sinuses and couldn’t breathe,” Srdjan says. “And Federer tried in every possible way to disrespect him because of his breathing problem.” Novak defeated Stanislas Wawrinka over five sets but frequently had to call the trainer onto the court. Afterward, Federer said Novak’s problems were a “joke.”

“He showed himself to be the best player in the world but not as a good person at that time,” Srdjan says of Federer. “Nobody has ever treated Novak like this. I don’t understand why Federer is still playing tennis. I don’t know why he’s still playing—he’s already 34. ”

Novak has always had a way with physical comedy on court—his nickname is the Joker—but leapfrogging Federer, the fans’ favorite, left the Serb sometimes unloved by the public. “I have always explained to Novak that he comes from a small country, a bombed country, with many wars, and that he will have a rough path throughout his life,” Srdjan says. “Novak never did anything to hurt anybody. But the boos make him stronger.”

When Novak defeated Federer in the U.S. Open semifinal of 2011, “out of 24,000 people, 23,000 were cheering for Federer. [Novak] won the match, took the microphone and said, ‘You are the best crowd in the world,’” Srdjan says and points to his temple. “This is his mental strength—like granite.”

That’s a quality Srdjan believes Murray, his son’s close friend and now his fiercest rival, lacks. "Murray is a great, great talent, one of the biggest ever, and a big part of it is not being used, because his mindset is not calm,” Srdjan says. “He gets frustrated very easily. When he’s winning he has booming confidence, but once he starts losing, his mind turns around and he looks lost. He starts talking to his box, and this distracts his mind. If he learns to calm down, he will have a far bigger career than he has by now. I would love for Murray to achieve his potential.”

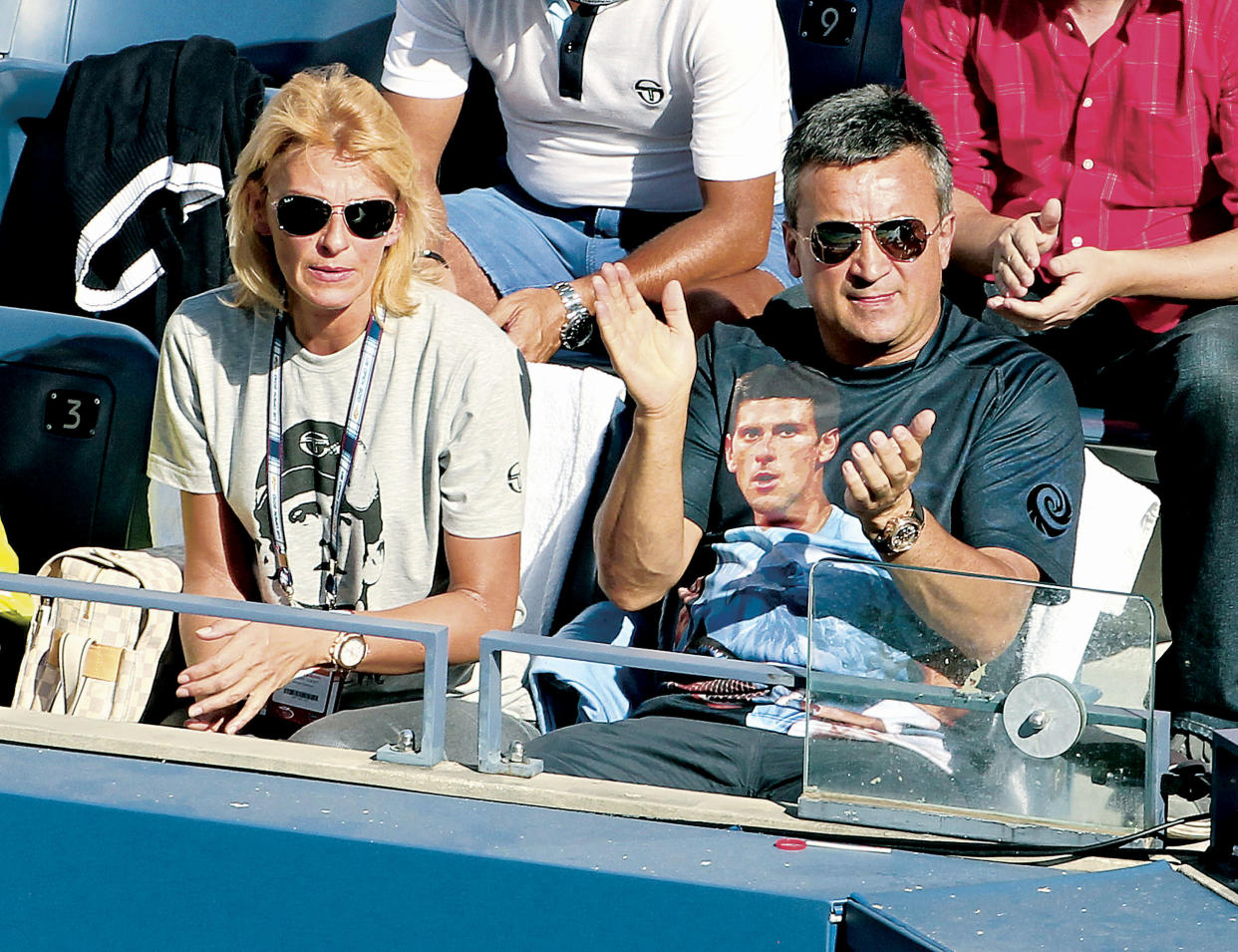

Over the years, Srdjan, a strong advocate of self-control, has had to relinquish nearly all control over his son’s career. He no longer goes to every tournament and does not choose his son’s coaching team. “I get so nervous watching him play now,” he says. “It’s very hard for me to hold my emotions in, so I only go every couple of months.”

One person Srdjan praises without qualification is former world No. 1 Boris Becker, who became Novak’s coach in December 2013. “Everything that Novak is going through, Becker has already been through,” he says. "Becker has brought Novak extra strength."

Even if Srdjan's influence over Novak’s life is waning, as every parent's must, his early high-stakes gamble and faith in his son has paid off. The day after our meeting, Novak ground down Kazakhstan’s Mikhail Kukushkin over five sets and put Serbia on the path to a Davis Cup victory. Normal service had been resumed.

Related Articles

Yahoo News

Yahoo News